Lausanne Global Analysis · January 2018

SHARE:

Welcome to the January issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis, which is also available in Portuguese and Spanish. We look forward to your feedback on it.

In this issue we examine the example of persecuted Christians in Egypt in witnessing to the gospel through forgiveness; we suggest why Christians should engage with supporters of the Gülen Movement; we ask why and how we should get involved in international student ministry; and we look at Polycentric Missiology: twenty-first-century mission ‘from everyone to everywhere’.

January 2018 Issue Overview

David Taylor

Welcome to the January issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis, which is also available in Portuguese and Spanish. We look forward to your feedback on it.

In this issue we examine the example of persecuted Christians in Egypt in witnessing to the gospel through forgiveness; we suggest why Christians should engage with supporters of the Gülen Movement; we ask why and how we should get involved in international student ministry; and we look at Polycentric Missiology: twenty-first-century mission ‘from everyone to everywhere’.

‘Throughout history, the Copts, the indigenous Christians of Egypt, have endured sporadic and sometimes intense times of persecution’, writes Wafik Wahba (Associate Professor of Global Christianity at Tyndale Seminary in Toronto, Canada). Nevertheless, they live in harmony with the larger community, contributing to its overall well-being. Many moderate Muslims enjoy amicable relationships with their Christian neighbours. However, growing traditionalist attitudes are creating increased tensions, with Islamists viewing the existence of other religious communities as a threat to Islam. As a result, Christians have often retreated into their own communities or emigrated. However, the extraordinary Christian response to the violent attacks that have taken place since 2013 has provided many opportunities for witness to the gospel and a renewed sense of mission to the larger community. Christians did not seek revenge; instead they extended forgiveness to those who murdered their loved ones. Media reported these attitudes of forgiveness. This powerful testimony to the gospel of love and forgiveness amid hatred is raising curiosity about the Christian faith. The global church is enriched by the faithful witness of many Egyptian Christians whose faith exemplifies the true meaning of hope. It is being reminded anew that at the heart of the Christian witness is a capacity to suffer for Christ. ‘The global Church is called faithfully to pray for the Church of the Martyrs, as the Christians of Egypt seek faithfully to live the gospel of love and forgiveness during times of suffering and persecution’, he concludes.

‘The Gülen Movement, or Hizmet, is today arguably the largest and most dynamic Muslim movement across the globe’, writes Peter Riddell (Vice Principal Academic at Melbourne School of Theology). Fethullah Gülen’s message to his supporters is to integrate their Islamic faith into their daily lives and instil this in their children through education. His approach is built on the concept of Temsil rather than Tebligh, of presence rather than proselytisation. The other core pillar of Hizmet activity is interfaith and intercultural dialogue. The Gülen Movement is reeling from the current campaign against it in Turkey. However, it has been a genuinely international movement for many years. As it struggles in Turkey, it may well flourish elsewhere. Christians can learn much from it. The success of a subtle Islamic values-based but non-Sharia focus on education to spread the message is evident. The movement speaks the language of the twenty-first century, yet reinforces traditional social and moral values. Its diverse activities, drawing on an incarnational approach of positive presence rather than overt preaching among the unconvinced, are compelling. Christians should engage with its supporters. There is much that both share in terms of a moral lifestyle, a values-based approach to the modern world, and a desire to please God. However, ultimately, the two messages are mutually exclusive in certain ways. ‘Yet these differences should not be allowed to prevent the formation of genuine friendships and meaningful and fruitful Christian-Gülen engagement’, he concludes.

‘The first world-wide gathering of International Student Ministry (ISM) leaders was convened in September 2017 as the Lausanne ISM Global Leadership Forum: Charlotte’17’, writes Leiton Chinn (Lausanne Catalyst for International Student Ministry, 2007 – 2017). The stage is now set for the ISM movement to grow deeper roots globally. God is sending the mission field to our campuses in the form of five million international students globally today, and a projected eight million by 2025. Although the strategic importance of ISM is obvious, church and mission leaders have often failed to see the tremendous potential for world missions to and through foreign students who are appreciative of hospitality and often open and curious while living abroad. They are also potential world leaders, nation builders, and transformation agents. Furthermore, Christian returnees can play significant roles in establishing the universal Church. Local churches are discovering how enriching it is to have a ministry among international students, while ISM can play a key role in the work of mission agencies and campus-based ministries. Most Christians are not ‘called’ to serve as long-term professional missionaries or as self-supporting ‘tent-maker’/BAM missionaries in another country. However, staying at home does not mean we cannot engage in cross-cultural, global ministry. ISM is one avenue for participating in world missions at home. ‘What is your context of ministry, and what next steps could you consider in exploring how your ministry might include ISM in its strategic plan?’, he asks.

‘The Edinburgh 1910 World Missionary Conference . . . was the birthplace of the modern ecumenical movement . . . leading to the formation of the International Missionary Council, the World Council of Churches, and the Lausanne Movement’, writes Allen Yeh (professor in the Cook School of Intercultural Studies at Biola University). In 2010, five major missionary conferences sought to be the successor to Edinburgh 1910. They are representative of where Christian missions today sees itself, in thought and praxis. Polycentricism is how mission is done today, in light of the shift of Christianity’s center of gravity to the Global South. Today, mission is ‘from everyone to everywhere’, so multiple conferences are needed. Mission conferences are where things start, and it is important to understand starting points. If the future of mission is polycentric, the entire global church needs to work together to bring the gospel to the nations. It has yet to fulfill Jesus’s high priestly prayer—to be unified in order to be a missiological sign and witness to the world. Ecumenism does not mean we compromise our theological integrity; holding to both unity and truth is the standard to which Jesus calls his church. Christianity continues to maintain its role as the largest religion in the world (though not the fastest-growing). However, even more so, Christianity is the most geographically widespread. ‘Unity in diversity is a much more important characteristic than speed of growth, ensuring that Christianity is poised for a strong future’, he concludes.

We hope that you find this issue stimulating and useful. Our aim is to deliver strategic and credible analysis, information and insight so that as a leader you will be better equipped for the task of world evangelization. It’s our desire that the analysis of current and future trends and developments will help you and your team make better decisions about the stewardship of all that God has entrusted to your care.

Please send any questions and comments about this issue to analysis@lausanne.org. The next issue of The Lausanne Global Analysis will be released in March.

David Taylor serves as the Editor of the Lausanne Global Analysis. David is an international affairs analyst with a particular focus on the Middle East. He spent 17 years in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, most of it focused on the Middle East and North Africa. After that he spent 14 years as Middle East Editor and Deputy Editor of the Daily Brief at Oxford Analytica. David now divides his time between consultancy work for Oxford Analytica, the Lausanne Movement and other clients, also working with Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), the Religious Liberty Partnership and other networks on international religious freedom issues.

David Taylor serves as the Editor of the Lausanne Global Analysis. David is an international affairs analyst with a particular focus on the Middle East. He spent 17 years in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, most of it focused on the Middle East and North Africa. After that he spent 14 years as Middle East Editor and Deputy Editor of the Daily Brief at Oxford Analytica. David now divides his time between consultancy work for Oxford Analytica, the Lausanne Movement and other clients, also working with Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), the Religious Liberty Partnership and other networks on international religious freedom issues. Witnessing to the Gospel through Forgiveness - A living example from the persecuted Christians in Egypt

Witnessing to the Gospel through Forgiveness - A living example from the persecuted Christians in EgyptWafik Wahba

On April 9, 2017, as Egyptian Christians were celebrating Palm Sunday, carrying palm branches and chanting ‘Hosanna in the Highest’, coordinated bomb attacks on major churches in Alexandria and Tanta in northern Egypt left tens of people dead and hundreds seriously injured. The joyful celebration turned into mourning across the country. The attack was one in a series of attacks on churches and Christians that has left thousands dead and injured. During August 2013 alone, over 70 churches and Christian institutions, along with hundreds of Christian homes and businesses, were attacked or burned.

during the 7th,

12th & 14th centuries

Since 12th century

Christians have

been minority

Throughout history, the Copts—the indigenous Christians of Egypt—have endured sporadic and sometimes intense times of persecution[1]:

In the second and third centuries, 16 percent of Egypt’s population was Christian (the highest percentage in the Roman Empire at the time). As a result, Egyptian Christians withstood the worst of the Roman persecution, with thousands put to death by the authorities.

The Copts also endured dreadful persecutions during the seventh, twelfth, and fourteenth centuries. Thousands of churches and monasteries were destroyed, while countless Christians were massacred or forced to change their religion.

By the twelfth century, Christians ceased to form a majority and since then have been a minority in their native land.

Why the attacks?

One of the pressing questions that usually arises in such a context is, ‘why the attacks on Christians?’ After all, the Copts never initiated attacks on others; on the contrary, they live in harmony with the larger community contributing to the overall well-being of their society. The majority of those who attend Christian schools in Egypt, who are treated in Christian hospitals or who benefit from the social services offered by Christian organizations are non-Christians. So why visit such atrocities on peaceful Egyptian Christians?

Christian and Muslim communities have coexisted in Egypt for thirteen centuries, one of the longest examples of coexistence. The history of their interaction is long and rich, carrying several layers of memories and events. Some of those memories are painful and discouraging, others are hopeful and promising.

Christian-Muslim relationships are often viewed through the lenses of the perception of the other; the way in which each community perceives the other usually results in certain attitudes and actions:

- Many moderate Muslims enjoy amicable relationship with their Christian neighbours, affirming a culture of peaceful coexistence and mutual respect.

- However, growing traditionalist attitudes are creating increased tension between Christians and Muslims.

- Such tension should be viewed in the larger context of the current socio-political structure of the country.

DURING THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, EGYPT SOUGHT TO ADOPT MODERNIZING PROGRAMS IN EDUCATION, SOCIAL LIFE, AND POLITICAL SYSTEMS.

Islamic revivalism

During the twentieth century, Egypt sought to adopt modernizing programs in education, social life, and political systems. Principles of coexistence and mutual respect between the two religious communities were key elements. Unfortunately, such programs failed to provide long-term viable social or political reform due to corruption, dictatorial models of leadership, and various outside forces trying to steer the country in one direction or another.

As these programs failed to create stable socio-political systems, a new surge of Islamic revivalism emerged during the second half of the twentieth century, trying to fill the socio-political void. It took the form of increased personal and public observance, such as a renewed commitment to attending mosque or wearing traditional Islamic dress as a way of asserting Islamic identity against secularization and Western-style modernization. Often such modernization is perceived as ‘Christian’.

Meanwhile, Egypt saw a proliferation of religious programs in education, Islamic publications, and media programs, while the masses were encouraged to adhere to Islamic religious observances through the influence of charismatic preachers. Such intensification of religious fervour created a new commitment among the masses to adhere to the ‘straight path of Islam’ against a perceived disbelief and infidelity inherent in Christianity and adopted by Christians. It created an intensified awareness of religious differences between Christians and Muslims.

Global tensions

Global tensions

Religious tensions at the global level are also affecting Christian-Muslim relationships in countries like Egypt.[2] Many Muslims are not able to distinguish between the secularized structure of Western societies and Christianity. Political decisions and interaction with the West are often perceived as an Islamic-Christian struggle over domination of the world’s resources and territories. Some traditionalist Islamists even view the Western agenda as a deliberate offense against Muslims and Islam. Accordingly, Christian communities, as in Egypt, become an easy target in attacks on the Western agenda which is perceived to be ‘Christian’.

In a rapidly changing world of social conflicts, and political and economic instability, feelings of distress sometimes result in irrational reactions, a reality that often colors the daily encounters between Christians and Muslims in Egypt. In the assertion of an Islamic identity against such socio-economic and political upheavals, Christian-Muslim relations usually suffer the most. While Christians and Muslims in Egypt are facing the same socio-political problems and economic strains, Christians sometimes become the targets for attacks as a way of venting Muslim frustration.

THE VERY PRESENCE OF CHRISTIANS IN A PREDOMINANTLY MUSLIM SOCIETY LIKE EGYPT IRRITATES MUSLIMS

Zero sum mentality

The very presence of Christians in a predominantly Muslim society like Egypt irritates Muslims, particularly traditionalist Islamists, who seek the creation of an Islamic community based on Islamic principles. From their point of view, Islam is the final and only true faith. Therefore, other communities should submit to God and God’s law as described in Islam. The expectation is that all other communities including Christians will come to accept the final and true faith. Therefore, the existence of other religious communities (even as a minority) is considered a challenge or a threat to Islam itself.

Overall, the presence of Christians in predominantly Muslim societies has attracted envious suspicion and reproach. They are accused of possessing hidden resources or exercising a power beyond their number—conspiracy theory-based influence that offends the pride of those who feel they should properly exercise their functions. Because of the prosperity of some Christians, along with their notable role in administration and finance, they become targets for anger that has no legitimate cause.

Such emotions are often undefined, and Christians’ attempts to be public-spirited, to assimilate, or even be apologetic, may only serve to fuel the animosity. In such a context, Christian self-definition and self-fulfillment can only be attained within the limitation of the socio-political framework drawn by Islamic rule. Shaped by such a cluster of religious, cultural, and political circumstances, a constant theme for the Copts has been their destiny and even survival in coexistence with Islam.

Isolated communities

This in turn has created a sense of mutual isolation and hostility between the two communities that did not exist before. Despite the influence of a semi-secularized state system that affirms one citizenship under a common civil law, the communal mentality and cultural isolation persist, with both communities unable to appreciate each other’s religious tradition. Isolation often creates misconceptions on both sides.

From an Islamic point of view, what is true and acceptable is what the larger society upholds as true. Since Christians uphold religious beliefs and values that differ from and even contradict this norm, they are often viewed with suspicion. From the traditionalist point of view, non-Muslims are ‘unbelievers’ or ‘infidels’ whose religious beliefs and lifestyle cannot be tolerated. Muslims in general are concerned that Christians exhibit a lifestyle that is not compatible with what Islam perceives as the true worship of God and a godly lifestyle.

As a result, Christians have resolved to create their own communities (often inside the church) within the larger society, as their way of maintaining their religious beliefs and values against Islamic criticism and sometimes forced conversion. Such cultural hibernation became a means for survival and upholding a historical and cultural identity that otherwise will be engulfed by the larger society. The ultimate escape out of this strained social context is leaving the country altogether. More than half a million Copts have emigrated from Egypt during the last seven years alone, adding to the three million already living outside Egypt.

Power of forgiveness

THE EXTRAORDINARY CHRISTIAN RESPONSE TO THE VIOLENT ATTACKS THAT HAVE TAKEN PLACE SINCE 2013 HAS PROVIDED MANY OPPORTUNITIES FOR WITNESS TO THE GOSPEL.

While many Christians struggle to choose between leaving the country or enduring more suffering, the extraordinary Christian response to the violent attacks that have taken place since 2013 has provided many opportunities for witness to the gospel and a renewed sense of mission to the larger community. Christians did not seek revenge; instead they extended forgiveness to those who murdered their loved ones. Many Christian families embrace martyrdom as a gift from God and to God, while keeping a balance between their love for life and their willingness to die for Christ. As one of the bishops put it at a mass funeral of the martyrs:

Implications

Implications

This powerful Christian testimony to the gospel of love and forgiveness amid hatred will have a positive impact on the attitudes of many Muslims towards Christianity and the Christians. It raises curiosity about the Christian faith and the gospel of forgiveness prompting many to ask themselves, ‘what kind of faith is this?’ Meanwhile, many Christians have been empowered by the testimonies of those who boldly extended love and forgiveness, giving them a renewed sense of mission amid suffering.

What is happening in Egypt is not a remote event in church history, but a living testimony to the power of the Christian faith. The global church is enriched by the faithful witness of many Egyptian Christians whose faith exemplifies the true meaning of hope. The global church is being reminded anew that at the heart of the Christian witness is a capacity to suffer for Christ. ‘For it has been granted to you on behalf of Christ not only to believe in him, but also to suffer for him’ (Phil. 1:29). Life in Christ is also a call to faithfulness till death.

Being faithful witnesses, Christians not only suffer for Christ but also hope for a glorified future with God. The Palm Sunday Egyptian martyrs instantly exchanged their bloodied earthy robes for martyrs’ robes washed white in the blood of the Lamb; and their earthly palm branches were exchanged for heavenly ones as they stood worshiping the Lamb seated on the throne (Rev 7).

The global church is called faithfully to pray for the church of the martyrs, as the Christians of Egypt seek faithfully to live the gospel of love and forgiveness during times of suffering and persecution.

Endnotes

Islamic revivalism

During the twentieth century, Egypt sought to adopt modernizing programs in education, social life, and political systems. Principles of coexistence and mutual respect between the two religious communities were key elements. Unfortunately, such programs failed to provide long-term viable social or political reform due to corruption, dictatorial models of leadership, and various outside forces trying to steer the country in one direction or another.

As these programs failed to create stable socio-political systems, a new surge of Islamic revivalism emerged during the second half of the twentieth century, trying to fill the socio-political void. It took the form of increased personal and public observance, such as a renewed commitment to attending mosque or wearing traditional Islamic dress as a way of asserting Islamic identity against secularization and Western-style modernization. Often such modernization is perceived as ‘Christian’.

Meanwhile, Egypt saw a proliferation of religious programs in education, Islamic publications, and media programs, while the masses were encouraged to adhere to Islamic religious observances through the influence of charismatic preachers. Such intensification of religious fervour created a new commitment among the masses to adhere to the ‘straight path of Islam’ against a perceived disbelief and infidelity inherent in Christianity and adopted by Christians. It created an intensified awareness of religious differences between Christians and Muslims.

Religious tensions at the global level are also affecting Christian-Muslim relationships in countries like Egypt.[2] Many Muslims are not able to distinguish between the secularized structure of Western societies and Christianity. Political decisions and interaction with the West are often perceived as an Islamic-Christian struggle over domination of the world’s resources and territories. Some traditionalist Islamists even view the Western agenda as a deliberate offense against Muslims and Islam. Accordingly, Christian communities, as in Egypt, become an easy target in attacks on the Western agenda which is perceived to be ‘Christian’.

In a rapidly changing world of social conflicts, and political and economic instability, feelings of distress sometimes result in irrational reactions, a reality that often colors the daily encounters between Christians and Muslims in Egypt. In the assertion of an Islamic identity against such socio-economic and political upheavals, Christian-Muslim relations usually suffer the most. While Christians and Muslims in Egypt are facing the same socio-political problems and economic strains, Christians sometimes become the targets for attacks as a way of venting Muslim frustration.

THE VERY PRESENCE OF CHRISTIANS IN A PREDOMINANTLY MUSLIM SOCIETY LIKE EGYPT IRRITATES MUSLIMS

Zero sum mentality

The very presence of Christians in a predominantly Muslim society like Egypt irritates Muslims, particularly traditionalist Islamists, who seek the creation of an Islamic community based on Islamic principles. From their point of view, Islam is the final and only true faith. Therefore, other communities should submit to God and God’s law as described in Islam. The expectation is that all other communities including Christians will come to accept the final and true faith. Therefore, the existence of other religious communities (even as a minority) is considered a challenge or a threat to Islam itself.

Overall, the presence of Christians in predominantly Muslim societies has attracted envious suspicion and reproach. They are accused of possessing hidden resources or exercising a power beyond their number—conspiracy theory-based influence that offends the pride of those who feel they should properly exercise their functions. Because of the prosperity of some Christians, along with their notable role in administration and finance, they become targets for anger that has no legitimate cause.

Such emotions are often undefined, and Christians’ attempts to be public-spirited, to assimilate, or even be apologetic, may only serve to fuel the animosity. In such a context, Christian self-definition and self-fulfillment can only be attained within the limitation of the socio-political framework drawn by Islamic rule. Shaped by such a cluster of religious, cultural, and political circumstances, a constant theme for the Copts has been their destiny and even survival in coexistence with Islam.

Isolated communities

This in turn has created a sense of mutual isolation and hostility between the two communities that did not exist before. Despite the influence of a semi-secularized state system that affirms one citizenship under a common civil law, the communal mentality and cultural isolation persist, with both communities unable to appreciate each other’s religious tradition. Isolation often creates misconceptions on both sides.

From an Islamic point of view, what is true and acceptable is what the larger society upholds as true. Since Christians uphold religious beliefs and values that differ from and even contradict this norm, they are often viewed with suspicion. From the traditionalist point of view, non-Muslims are ‘unbelievers’ or ‘infidels’ whose religious beliefs and lifestyle cannot be tolerated. Muslims in general are concerned that Christians exhibit a lifestyle that is not compatible with what Islam perceives as the true worship of God and a godly lifestyle.

As a result, Christians have resolved to create their own communities (often inside the church) within the larger society, as their way of maintaining their religious beliefs and values against Islamic criticism and sometimes forced conversion. Such cultural hibernation became a means for survival and upholding a historical and cultural identity that otherwise will be engulfed by the larger society. The ultimate escape out of this strained social context is leaving the country altogether. More than half a million Copts have emigrated from Egypt during the last seven years alone, adding to the three million already living outside Egypt.

Power of forgiveness

THE EXTRAORDINARY CHRISTIAN RESPONSE TO THE VIOLENT ATTACKS THAT HAVE TAKEN PLACE SINCE 2013 HAS PROVIDED MANY OPPORTUNITIES FOR WITNESS TO THE GOSPEL.

While many Christians struggle to choose between leaving the country or enduring more suffering, the extraordinary Christian response to the violent attacks that have taken place since 2013 has provided many opportunities for witness to the gospel and a renewed sense of mission to the larger community. Christians did not seek revenge; instead they extended forgiveness to those who murdered their loved ones. Many Christian families embrace martyrdom as a gift from God and to God, while keeping a balance between their love for life and their willingness to die for Christ. As one of the bishops put it at a mass funeral of the martyrs:

True, we love martyrdom. But we also love life. We don’t hate life on earth. God created us on earth to live, not die. The fact that we accept death doesn’t mean our blood is cheap, and it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t matter to us. We do not commit suicide. But we witness for Christ, whether by our lives or by our transition to heaven. If we live, we live for the Lord; and if we die, we die for the Lord.[3]

Social media and other media reported such extraordinary attitudes of Christian forgiveness, interviewing members of the families who have lost loved ones. They openly spoke about their Christian faith and what it means to extend God’s forgiveness. Such powerful Christian testimonies had a lasting impact on the larger Muslim community that was stunned by the Christian response. In many instances, Muslims were outraged at the blind and evil hatred behind these atrocities, expressing their astonishment at Christians’ emphasis on love and forgiveness.

This powerful Christian testimony to the gospel of love and forgiveness amid hatred will have a positive impact on the attitudes of many Muslims towards Christianity and the Christians. It raises curiosity about the Christian faith and the gospel of forgiveness prompting many to ask themselves, ‘what kind of faith is this?’ Meanwhile, many Christians have been empowered by the testimonies of those who boldly extended love and forgiveness, giving them a renewed sense of mission amid suffering.

What is happening in Egypt is not a remote event in church history, but a living testimony to the power of the Christian faith. The global church is enriched by the faithful witness of many Egyptian Christians whose faith exemplifies the true meaning of hope. The global church is being reminded anew that at the heart of the Christian witness is a capacity to suffer for Christ. ‘For it has been granted to you on behalf of Christ not only to believe in him, but also to suffer for him’ (Phil. 1:29). Life in Christ is also a call to faithfulness till death.

Being faithful witnesses, Christians not only suffer for Christ but also hope for a glorified future with God. The Palm Sunday Egyptian martyrs instantly exchanged their bloodied earthy robes for martyrs’ robes washed white in the blood of the Lamb; and their earthly palm branches were exchanged for heavenly ones as they stood worshiping the Lamb seated on the throne (Rev 7).

The global church is called faithfully to pray for the church of the martyrs, as the Christians of Egypt seek faithfully to live the gospel of love and forgiveness during times of suffering and persecution.

Endnotes

- Editor’s Note: See article by Thomas Harvey entitled, ‘The State and Religious Persecution: the global rise of secular and religious restriction and their impact on missions’, in March 2016 issue of Lausanne Global Analysishttps://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2016-03/state-and-religious-persecution. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by John Azumah entitled, ‘The Challenge of Radical Islam: an evangelical response’ in March 2015 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2015-03/the-challenge-of-radical-islam. ↑

- Editor’s Note: Quote from Bishop Paula, the Coptic Orthodox Bishop of the city of Tanta where one of the attacks took place on PalmSunday 2017. For the exact quote, see a letter from Ramez Atallah, General Director of the Bible Society of Egypt, as quoted here on a blog from Jason McKnight http://www.jasonmcknight.org/?m=201704; and see this article from the Scottish Bible Society https://scottishbiblesociety.org/2017/04/not-just-a-legend/. ↑

- Feature image from ‘Coptic Good Friday Mass‘ by Chaoyue 超越 PAN 潘 (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

- ‘Copts’ protest, Dublin‘ by Tomasz Szustek (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

- ‘The face of egypt: muslim and christian – Egypt Uprising protest Melbourne 4 Feb 2011‘ by Takver (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Wafik Wahba (ThM, Princeton; PhD, Northwestern University) is Associate Professor of Global Christianity at Tyndale Seminary in Toronto, Canada. He has taught Theology, Global Christianity, Cultural Contextualization and Islam in the USA, Middle East, Africa, South East Asia and South America, and has pastored churches in Chicago, IL and Toronto, Canada. His book entitled Christianity and Islam: Global Perspectives will be published in 2018 by Intervarsity Academic.

Wafik Wahba (ThM, Princeton; PhD, Northwestern University) is Associate Professor of Global Christianity at Tyndale Seminary in Toronto, Canada. He has taught Theology, Global Christianity, Cultural Contextualization and Islam in the USA, Middle East, Africa, South East Asia and South America, and has pastored churches in Chicago, IL and Toronto, Canada. His book entitled Christianity and Islam: Global Perspectives will be published in 2018 by Intervarsity Academic. What Can Christians Learn from a Global Islamic Movement? - Meet the Gülen Movement practising presence more than proselytisation

What Can Christians Learn from a Global Islamic Movement? - Meet the Gülen Movement practising presence more than proselytisationPeter G. Riddell

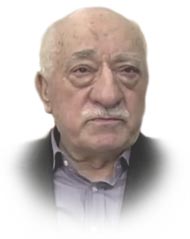

The world’s largest Muslim movement is in crisis. Tens of thousands of supporters of the vast international network led by Islamic theologian and philosopher Fetullah Gülen languish in prisons in Turkey and other countries. Gülen himself faces extradition to Turkey from the US to face charges of subversion if Washington accedes to the Turkish request. Ankara is now linking the release of American Pastor Andrew Brunson, imprisoned on trumped-up terrorism and espionage charges, with Gülen’s extradition.

Gülen’s perspective on religion and philosophy

Gülen was born in rural eastern Turkey in 1941. His early education was heavily influenced by Sufism, the mystical stream of Islam. He spent two decades working as a state imam during his 20s and 30s, during which time he established a reputation as a charismatic preacher and gifted teacher of the Qur’an. The extent of his following in eastern Turkey concerned successive governments of the secular republic, and he was jailed for a time after military coups in 1971 and 1980.

Gülen was born in rural eastern Turkey in 1941. His early education was heavily influenced by Sufism, the mystical stream of Islam. He spent two decades working as a state imam during his 20s and 30s, during which time he established a reputation as a charismatic preacher and gifted teacher of the Qur’an. The extent of his following in eastern Turkey concerned successive governments of the secular republic, and he was jailed for a time after military coups in 1971 and 1980.GÜLEN WAS NOT ATTRACTED TO THE GROWING CALLS FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF CONSERVATIVE SHARIA STATES AROUND THE MUSLIM WORLD.

Gülen was concerned with the state of Turkish youth, which he considered to be losing its way and its faith under the secular republic. However, he was not attracted to the growing calls for the establishment of conservative Sharia states around the Muslim world. His message to his rapidly growing base of supporters was that they should integrate their Islamic faith in their daily lives and instil this in their children through education to meet the challenges of the modern world and to stay true to their faith.Unlike many of his more combative Islamic contemporaries, Gülen shunned anti-Western rhetoric. Indeed, he had a profound admiration for some Western thinkers such as Kant and Descartes. The biggest influence on Gülen was the great Turkish reformist theologian, Beduizzaman Said Nursi (1877 – 1960). He had advocated that Muslims and Christians, and indeed other people of faith, should join forces to resist the influence of atheist and materialist philosophies that were bringing such decay to twentieth-century societies.Gülen built on Nursi’s ideas to propose a dichotomy between religious internalism and externalism:

The former, clearly influenced by his own Sufi formation, was concerned with faith-based considerations of internal moral reform.

The external perspective was focused on institutional and legal mechanisms for shaping individuals and society, especially the Sharia.

GÜLEN ARGUED THAT THE FUTURE LAY IN AN ISLAMIC VALUES-BASED LIFESTYLE, RATHER THAN A TOP-DOWN SHARIA-DRIVEN APPROACH.

Gülen argued that the future lay in an Islamic values-based lifestyle, rather than a top-down Sharia-driven approach. His remedy was built on the concept of Temsil rather than Tebligh, of presence rather than proselytisation. This idea of presence bears resemblances to the Christian idea of incarnational ministry, which has become such a feature of relief and development work in Muslim societies by Christian aid agencies, postponing active preaching in favour of subtle witness through Christian presence.

Gülen’s message had a powerful appeal in Turkish society, which had experienced a half-century of secular rule and several coups. As he developed his notion of active pietism while he preached around Anatolia in the 1970s, a movement formed around him and gathered momentum. In time, his message and call to action materialised through the establishment of the first Gülen School in Izmir, followed by another in Istanbul, in the early 1980s.

The Hizmet and education

These schools were the foundation stones for what became the Gülen Movement, or Hizmet, which today is arguably the largest and most dynamic Muslim movement across the globe. In little more than 30 years, one school has become a major international network of over 700 primary and secondary institutions, fanning out from Turkey through Central Asia to East Asia and throughout the West, with millions of followers in around 150 countries. The US alone is home to around 100 of these schools. Additionally, a network of Gülen private universities was established in Turkey and flourished throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century.

THE STUDY OF ISLAM IS NOT INDEPENDENTLY FEATURED IN THE CURRICULUM TO A GREAT DEGREE, BUT THE ISLAMIC VALUES THAT UNDERPIN GÜLEN’S PHILOSOPHY STEER SCHOOL ACTIVITIES.

The curriculum in Gülen schools is built on modern subjects, as found in other school systems. The study of Islam is not independently featured in the curriculum to a great degree, but the Islamic values that underpin Gülen’s philosophy steer school activities. Teachers are expected to serve as moral role models, avoiding smoking, alcohol, and divorce. All knowledge is regarded as God-given and as such, the pursuit of ‘secular’ knowledge is accepted as part of the remit. While the educational institutions represent the flagship of the movement, it is very active in other ways:

- It recognises the importance of the media to disseminate its modern, Islamic values-based message, and, to this end, there are a number of TV and radio stations, as well as newspapers and magazines, connected with the movement.

- Gülen himself and many gifted people across the movement write books and articles, presenting the core message of integrating the Islamic faith and modern living to produce wholesome, morally upright and purpose-driven communities.

- The movement is active in business networks across the world, as well as in charitable activities.

The other core pillar of Hizmet activity alongside education is interfaith and intercultural dialogue. The Gülen Movement website[1] pays particular attention to this as a primary goal. There are seven principles of interfaith dialogue as articulated by Gülen. Three of the principles specify the broad approach to dialogue, aiming for a wide range of partners in the interaction. Gülen highlights the pious values inherent in all religions:

Even though we may not have common grounds on some matters, we all live in this world and we are passengers on the same ship. In this respect, there are many common points that can be discussed and shared with people from every segment of society.[2]

One of the principles is based on an appreciation of diversity, citing verse 48 of Qur’an chapter 5 which states:

To each among you have We prescribed a Law and an Open Way. If Allah had so willed, He would have made you a single people, but (His plan is) to test you in what He has given you: so strive as in a race in all virtues.

Other principles centre upon ethical considerations in engaging in dialogical interactions, calling for sincerity in dialogue, as well as gentleness and tolerance. Gülen also calls for love as a central element in human interactions, clearly showing the influence of his early Sufi educational formation.Gülen himself has led the way in promoting dialogue. When he met the late Pope John-Paul II in 1998, Gülen proposed establishing a joint Divinity School in Urfa, Turkey, which according to Muslim tradition is the birthplace of Abraham. Gülen has also stood against proposals which he considered unhelpful, such as the request in 2001 from Al-Azhar to the Pope for an official apology for the Crusades. Gülen argued that it was important to leave the past behind in shaping better relationships in the present and future.Gülen, and the vast movement which has gathered around him, have been outspoken in other ways:

Other principles centre upon ethical considerations in engaging in dialogical interactions, calling for sincerity in dialogue, as well as gentleness and tolerance. Gülen also calls for love as a central element in human interactions, clearly showing the influence of his early Sufi educational formation.Gülen himself has led the way in promoting dialogue. When he met the late Pope John-Paul II in 1998, Gülen proposed establishing a joint Divinity School in Urfa, Turkey, which according to Muslim tradition is the birthplace of Abraham. Gülen has also stood against proposals which he considered unhelpful, such as the request in 2001 from Al-Azhar to the Pope for an official apology for the Crusades. Gülen argued that it was important to leave the past behind in shaping better relationships in the present and future.Gülen, and the vast movement which has gathered around him, have been outspoken in other ways:- Gülen is unambiguous in his condemnation of terrorist attacks, and was the first Muslim leader to condemn the 9/11 attacks through an advertisement in the Washington Post.

- Organisations associated with the Gülen Movement around the world have typically been at the forefront of statements of condemnation of terrorist groups such as al-Qaida and Islamic State.

- These condemnations usually dismiss the Islamic credentials of the groups concerned and argue that they misinterpret the core messages of Islam.

ERDOĞAN HELD GÜLEN AND HIS MOVEMENT RESPONSIBLE FOR A SERIES OF CORRUPTION CHARGES THAT WERE LEVELLED AGAINST ERDOĞAN HIMSELF AND CAUSED A HUGE AND HUMILIATING SCANDAL IN 2013.

The high watermark for the movement was during the first decade of the twenty-first century, when it was supportive of the Islamizing programme of the AKP government under Prime Minister and later President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The movement had a following of several million, spread across the world, with the movement’s literature, including Gülen’s own writing, being translated into English, French, German, Russian, Spanish, Albanian, Urdu, and Malay/Indonesian. Many thousands of students had enrolled in Gülen schools and universities in Turkey and beyond. Gülen had himself decided to remain in the US after travelling there for medical treatment in 1999, following ongoing pressure and scrutiny on him from Turkish authorities. Nevertheless, he was able to continue to inspire his supporters no less effectively from his residence in Pennsylvania. However, the relationship between Gülen and his erstwhile ally Erdoğan had soured. Erdoğan, never one to brook competition, held Gülen and his movement responsible for a series of corruption charges that were levelled against Erdoğan himself and caused a huge and humiliating scandal in 2013. In December 2013, the AKP government closed many Gülen- inspired schools in Turkey and dismissed thousands of officials in the justice system from their posts, accusing them of being Gülen supporters. One year later, further arrests accompanied the closure of Gülen-affiliated media outlets which had been outspoken on the corruption scandal. In July 2016, the abortive coup—which some commentators argue was staged by the Erdoğan regime—triggered further widespread arrests and closures of Gülen institutions in Turkey. At the time of writing, those imprisoned on suspicion of having Gülen affiliations number over 50,000, with over 140,000 public sector employees dismissed from their jobs, accused of pro-Gülen sympathies. In addition, Turkey has used its influence to pressure other countries to detain people accused of Gülen affiliations. Some have complied, such as Somalia and Turkmenistan. Meanwhile, Gülen himself awaits the outcome of a Turkish extradition request to the US.

Implication for Christian leaders

Clearly, the Gülen movement is reeling from the campaign against it in Turkey. However, it has been a genuinely international movement for many years. As it struggles in Turkey, it may well flourish elsewhere among those who react against Erdoğan’s vitriolic campaign against Gülen. Erdoğan has lost favour across the West because of the increasingly totalitarian policies of his regime. In such a climate, the Gülen movement will win the sympathy vote outside Turkey. Christians can learn much from observing the methods and strategies of the Gülen movement. The success of a subtle Islamic values-based but non-Sharia focus on education to spread the message is evident. The movement speaks the language of the twenty-first century, yet reinforces traditional social and moral values. Its diverse activities, all drawing on an incarnational approach of positive presence rather than overt preaching among the unconvinced, is compelling.

CHRISTIANS SHOULD ENGAGE WITH SUPPORTERS OF THE GÜLEN MOVEMENT. THERE IS MUCH THAT BOTH CAN SHARE IN TERMS OF A MORAL LIFESTYLE AND A VALUES-BASED APPROACH TO THE MODERN WORLD.

Gülen spokespeople insist that the movement is committed to dialogue, not da’wa (Islamic mission). This claim bears further scrutiny, given that the Islamic faith is usually seen by Islamic scholars as the total package for life, not merely a set of doctrines. In that context, da’wa takes diverse forms, including dialogue, where Islamic values are modelled in the hope of attracting others to Islam. Anyone who has taken part in Gülen activities can discern a subtle yet clear Islamic overlay to the activities concerned. Hospitality is accompanied by public prayer; public events carry a clear Islamic identity.

The Gülen movement is certainly about da’wa, just as Christian incarnational presence that takes many forms is about mission:

That is far better than the in-your-face anti-Christian polemic of some other Islamic groups committed to a more activist da’wa.

Yet, in another way, Gülen da’wa represents a much greater challenge to Christianity, in Western countries at least, because it appeals to a largely post-Christian audience that is still seeking spiritual answers, but has been programmed to reject both institutionalised Christianity and assertive, polemical Islamic mission.

Christians should engage with supporters of the Gülen movement. There is much that both can share in terms of a moral lifestyle and a values-based approach to the modern world. However, ultimately, the two messages are mutually exclusive in certain ways, chiefly relating to the incompatibility between Christian Trinitarian monotheism and Islamic Unitarian monotheism, and radically different perspectives on the identity of Jesus Christ. Yet these differences should not be allowed to prevent the formation of genuine friendships and meaningful and fruitful Christian-Gülen engagement.

Endnotes

- See www.gulenmovement.com. ↑

- See www.gulenmovement.com/gulen-movement/values-promoted-by-gulen-movement. ↑

- ‘Fethullah Gülen visiting Ioannes Paulus II‘ image from Dialog Berlin by Forum für INTERKULTURELLEN Dialog FID e.V. (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE).

Peter G. Riddell is Vice Principal (Academic) at the Melbourne School of Theology and is also a Professorial Research Associate at SOAS, the University of London. He was previously Professor of Islamic Studies at the London School of Theology, and also held academic posts at SOAS, the University of London, the Institut Pertanian Bogor in Indonesia, and the Australian National University. Email: peter_riddell@yahoo.com.

Peter G. Riddell is Vice Principal (Academic) at the Melbourne School of Theology and is also a Professorial Research Associate at SOAS, the University of London. He was previously Professor of Islamic Studies at the London School of Theology, and also held academic posts at SOAS, the University of London, the Institut Pertanian Bogor in Indonesia, and the Australian National University. Email: peter_riddell@yahoo.com. The Mission Field Coming to Our Campuses - What is the relevance of international student ministry in our context?

The Mission Field Coming to Our Campuses - What is the relevance of international student ministry in our context?Leiton Chinn

The event that launched International Student Ministry (ISM) on to the global scene was the Lausanne 2004 Forum in Thailand, where Diaspora Ministry and International Student Ministry were introduced as a new strategic ministry special interest group. The Lausanne Occasional Paper 55, Diasporas and International Students: The New People Next Door, produced by the joint Diaspora and ISM groups at the Forum, authenticated ISM across the world as a significant and strategic mission.[1]

The first worldwide gathering of ISM leaders was convened in September 2017 as the Lausanne ISM Global Leadership Forum:

Charlotte’17, with over 100 leaders from 70 organizations and 23 countries.[2]

Growing mission field

God is sending the mission field to our campuses in the form of five million international students globally today, and a projected eight million by 2025. Europe and North America have been the primary destination regions for international students during the previous six decades, but the Asia-Pacific region is rapidly attracting foreign students because several nations have national goals for recruiting lucrative students from abroad, for example:

During my 40 years of mobilising the Church for ISM, I have adhered to the foundational need to share the biblical commands to practice hospitality and welcome the foreigner, and also the multi-faceted and mutual blessings of ministry among international students. Why? Because without a vision there will not be any engagement.

As Jesus did with the crowds in Matthew 9:36-38, a pastor or ministry/mission leader needs to ‘see’ the providential presence of international students (the world’s future influencers) studying on their campuses in order to feel compassion or conviction to extend God’s hospitality to the lost sheep from many nations.[3] Although the strategic importance of ISM is obvious, church and mission leaderships have often been oblivious to it.

Why engage with international students?

In 1975, a former international student gave a powerful message at the World Missions Conference of Park Street Church in Boston. That message, ‘The Great Blind-Spot in Missions Today’, was about ministry among international students, and how the church often failed to see the tremendous potential for world missions to and through foreign scholars.

Opportunities for mission

The blind-spot has been gradually diminishing over the last four decades as the church gains a vision about the strategic value of ISM, and a better understanding of the opportunities for mission among international students and scholars:

- These students are already here and now, on our campuses, in our communities, and in our churches; we do not need to wait to go somewhere, over there, in the future to participate in the Great Commission.

- They are sufficiently conversant in our language to study in our schools, or may be in a language institute to enhance the learning of our language. They would often appreciate the opportunity to practice our language with us (and while we do not need to be fluent in their native tongue, we could have them teach us some of their language). Volunteer language conversation is a wonderful service that naturally builds friendships to share about life and faith.

- They are generally willing to learn about our culture, history, and country and may wish to have host-country friends who can be cultural mentors.

- They are often more open, curious, and responsive to learning about Jesus while living abroad.

- They are freer to consider the gospel if they are away from a restrictive society, culture, and religion that is hostile towards Christianity.

- They are sometimes from unreached people-groups where the church does not yet exist or is in an infant stage.

- They are appreciative of hospitality and welcome relationships of mutual intercultural interaction, as well as the intergenerational social context of host-families where younger children, parents, and grandparents are valued along with peer-age adults.

International students are potential world leaders (politically and in their professions), nation builders, and transformation agents.

Furthermore, Christian returnees can play significant roles in establishing the universal Church; many of the senior evangelical leaders in Malaysia and Singapore in recent years were students in Australia in the 1960s and 1970s.

John Sung came to Christ in the US in the mid-1920s and returned to China as an evangelist; revival in China spread like wildfire. Bakht Singh, a Sikh, was attracted to Christ over a span of months while studying in the UK and then in Canada. He received Christ and returned to be an evangelist to India, just like John Sung in China and East Asia: ‘Bakht Singh’s New Testament church planting model multiplied to over 500 congregations in India and 200 congregations in Pakistan, plus a number in Europe and North America.’[4]

Informants and instructors

International students can also serve as ‘informants’ and ‘instructors’ that advance the mission movement. Two mega shifts in missions in the nineteenth and twentieth century were spurred on by the informants role provided by international students:

During the D. L. Moody student conference at Mt. Hermon, MA in 1886, a special ‘meeting of the ten nations’ was held in which students from ten countries shared briefly about the need for missionaries in their part of the world. Those ‘Macedonian calls’ fueled a response that resulted in the formation in 1888 of the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions which produced over 20,500 missionaries in the field.[5]

Dr. Ralph D. Winter’s development of the ‘hidden peoples’/unreached peoples concept in relation to the unfinished task of world evangelisation affected a paradigm shift in mission understanding and strategic planning.[6] What contributed to his emerging people-groups worldview? He told me that the Fuller Seminary School of World Missions (where he taught) had ‘10 students and 100 faculty’, explaining that he was the student learning about church growth and evangelism among the world’s diverse cultural sub-groups from ‘100 teachers’—his international student informants.

International students have played a tremendous role in the advance of missions understanding and needs, and will continue to be valuable instructors, if we are willing to listen and learn from them.They are also gifts of God to the host nation and church: an African seminary student was instrumental in the conversion of an Episcopal priest in the US, who later became a bishop and played a significant role in the evangelical stream within the US Episcopal Church. That stream has flowed into the new Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) denomination, and in turn, there is now significant interest and movement among Anglican mission and church leaders to foster ISM in the ACNA.

Local churches are discovering how enriching it is to have a ministry among international students:

- Substantial benefits and significant global impact can be achieved with a very modest ISM budget—high-yield but low (or no) financial cost.

- ISM provides a tangible dimension to a church’s mission vision, with engagement options for the congregation to participate in beyond prayer, member care, and financial support of overseas missionaries and ministries.

- A broad range of church members can be involved in ISM, from children to retirees, and utilize their varied gifts for service—hospitality, helping, administration, teaching, mercy, evangelism, leadership, etc.

- Returned or retired missionaries back home are extending their cross-cultural mission service by ministering among international students from the country or cultural-linguistic group they served overseas. We have several missionaries and other returned expatriate government or business people involved regularly in our church-based ISM. Furthermore, mission agencies may recommend or assign their candidates to participate in ISM as a pre-field cross-cultural training and learning experience.

- Many people who have had a desire to serve abroad, but are not able to for various reasons, are having a fruitful ministry with international students from the country or region of the world to which they had intended to go. They are now global missionaries at home, and sometimes in their homes.

- International student friends are ready-made language and cultural teachers for church members going to the students’ countries for long-term or short-term missions, study abroad, work, or simply a visit.

- International students may provide critical linkage to ministry/mission in their homeland, either personally after they return home or by giving a positive introduction to, and endorsement of, missionaries to their family, friends, and networks. Returnees could be gatekeepers that open the door for ministry by foreigners in their country.

Implications and responses

- What is your context of ministry, and what next steps could you consider in exploring how your ministry might include ISM in its strategic plan?

- If you are a church-based ministry, are there any ISMs in your area with which to collaborate? If not, and you have international students in your community, perhaps your members would volunteer to be ‘host-families/friends’ through the local campus International Student Services office, or language conversation partners with a language learning institute.

- If you are a campus-based ministry, how could ISM be promoted among your national students, and perhaps intentionally developed within your campus plans?

- If you are a mission agency, should ISM be adopted for your pre-field missionary training of candidates and also as a continuing option for returned and retired missionaries? How might Christian international students contribute as potential informants, mentors, and advocates before and after they return home?

Endnotes

- Editor’s Note: Downloadable PDF is available at https://www.lausanne.org/content/lop/lop-55. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See https://www.lausanne.org/gatherings/lausanne-ism-global-leadership-forum-charlotte17. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Sam George, entitled, ‘Is God Reviving Europe through Refugees?: Turning the greatest humanitarian crisis of our times into one of the greatest mission opportunities’ in May 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-05/god-reviving-europe-refugees. ↑

- Jonathan Bonk, ‘Thinking Small: Global Missions and American Churches,’ Missiology (April 2000). ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Allen Yeh, entitled, ‘The Future of Mission is from Everyone to Everywhere: a look at polycentric missiology” in this current issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2018-01/future-mission-everyone-everywhere. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Kent Parks, entitled, ‘Finishing the Remaining 29 Percent of World Evangelization: Disciple-Making Movements as a holistic and radical solution’ in May 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysishttps://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-05/finishing-the-remaining-29-of-world-evangelization. ↑

Leiton Edward Chinn has been mobilizing the church for ISM since 1977 and completed a ten-year tenure as Lausanne Catalyst for ISM in 2017. He served as President of the Association of Christians Ministering among Internationals [students] from 1999 – 2008. Leiton is married to Lisa Espineli Chinn, a former National ISM Director of InterVarsity USA, who was an international graduate student from the Philippines at Wheaton Graduate School.

Leiton Edward Chinn has been mobilizing the church for ISM since 1977 and completed a ten-year tenure as Lausanne Catalyst for ISM in 2017. He served as President of the Association of Christians Ministering among Internationals [students] from 1999 – 2008. Leiton is married to Lisa Espineli Chinn, a former National ISM Director of InterVarsity USA, who was an international graduate student from the Philippines at Wheaton Graduate School.

The Future of Mission is from Everyone to Everywhere - A look at polycentric missiology

Allen Yeh

Lausanne Global Analysis seeks to deliver strategic and credible information and insight from an international network of evangelical analysts to equip influencers of global mission. Browse all the past issues at lausanne.org/lga. The publication of the LGA is overseen by its Editorial Advisory Board. Articles represent a diversity of viewpoints within the bounds of our foundational documents. The views and opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the personal viewpoints of Lausanne Movement leaders or networks. Inquiries regarding the Lausanne Global Analysis may be addressed to analysis@lausanne.org.

---

Allen Yeh

Lausanne Global Analysis seeks to deliver strategic and credible information and insight from an international network of evangelical analysts to equip influencers of global mission. Browse all the past issues at lausanne.org/lga. The publication of the LGA is overseen by its Editorial Advisory Board. Articles represent a diversity of viewpoints within the bounds of our foundational documents. The views and opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the personal viewpoints of Lausanne Movement leaders or networks. Inquiries regarding the Lausanne Global Analysis may be addressed to analysis@lausanne.org.

---

No comments:

Post a Comment