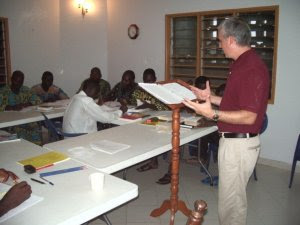

Dr. Crofford teaches a course on John Wesley's theology to students in Benin

Though my calling is to vocational Christian ministry, there have been transition times when I was very glad for my bank teller skills. It was honest work, and it provided for my family.Working as a bank teller required specialized training. Tellers must know how to process deposits, withdrawals, account inquiries, loan payments, and more. Banks hire trainers who show new recruits what to do and how to do it.

Like banks, the church also recognizes the value of training. God-called pastors require certain skills. They must know what to do and how to do it. This includes the preparation and delivery of a sermon, baptizing those of all ages, serving the Lord's Supper, making hospital visits, conducting funerals and weddings, providing pastoral counseling, and a dozen other tasks. These are vital skills for any pastor to be effective, and local churches expect that their pastor is able to perform them to an acceptable level, knowing that with time they will become more adept. In short, training is important.

Regarding business products: Simon Sinek observed:

- People don’t buy what you do. They buy why you do it.*

- Are we as a church effectively addressing this more advanced aspect of purpose?

The dangers of only training pastors and not educating them to think critically are real. Some years ago, a conservative Christian mission agency based in the United States sent missionaries to a West African nation. The mission agency equipped local leaders to plant churches throughout the country, in big cities and small villages. Within 15 years, their members numbered nearly 50,000. Over time, the mission’s priorities shifted, so they re-assigned the missionaries to other countries, leaving leadership of the churches in the hands of one of the local leaders who have proven himself capable. One day, he came across an attractive pamphlet about Jesus Christ. He read how Jesus is not God, but the first and highest being created by God. The leader began teaching what he had read inside. The growth of the church stalled and began to decline as 1/3 of its pastors left the denomination, not wishing to be part of a group that had unwittingly begun to promote a false belief. A key leader had been trained for a task but had apparently not received adequate theological education. Consequently, he was unprepared to critically engage with a contemporary manifestation of the ancient heresy of Arianism.

"History and Faith of the Biblical Communities," at Mount Vernon Nazarene University

The “what” and “how” of training are not sufficient. Pastors must understand why they do what they do, itself a natural outgrowth of studying and determining over time why they believe what they believe. Africa is awash in a sea of quasi-Christian teaching that has at-times incorporated elements of African Traditional Religion (ATR) into its thinking, particularly in how it presents the work of “prophets” who end up serving the same function as shamans. We need more than just a handful of theologians capable of separating theological wheat from chaff. Every individual - male or female - who expresses a call to ordained ministry must be given both training and theological education. They must be taught not only the content of faith but how to reflect theologically in-light of both what Scripture says and what the church has historically understood Scripture to mean. Only then can the church stay on-course through the rough seas and high winds of false doctrine. In-turn, pastors – effectively trained and theologically educated – must equip lay leaders in the church in the “what” and “how” of ministry, all the while carefully helping them to understand the “why” of our practice and belief. Orthodoxy (correct belief) and orthopraxy (correct practice) go hand-in-hand.The training only model, however well-intentioned, is inadequate. One of my supervisors told me soon after I took up my missionary teaching task: “Just give your students the information and make sure they give it back to you correctly on the exam. That’s all they need to do.” At the time, it seemed like good advice, but was it? An African teacher lamented: “The first missionaries came and gave us a book. We learned everything inside and began to teach it. Later, other missionaries came and gave us a second book that said different things than the first. So, we want you missionaries to tell us: Which book is correct?” Though the teacher was well-trained to do the work of a pastor, he was not able to critically reflect for himself and arrive at his own conclusions. He was helpless in the face of contradictory ideas advanced by writers of equal academic qualification. No amount of training could make up for the absence of critically reflective theological education.

Denominations that are growing and stable have understood that education – both in theology and the other academic disciplines – is not an enemy of faith but its enabler. Bertha Munro, the late long-time Dean of Eastern Nazarene College, was fond of telling her students: “There is no conflict between the best in education and the best of our Christian faith.” A tradesman teaches an apprentice what to do and how to do it. That is admirable and needed, yet education delves deeper, helping the student understand the rationale for belief and practice, no matter the field of service, creating a strong foundation on which a solid building can be erected.

Those who think that training ministers is enough may misunderstand the rationale behind theological education. For a student to construct a theology that is his or her own, sometimes he or she – under the gentle probing of a Seminary or University teacher – must set aside long-held beliefs that do not hold up under the closer scrutiny of a more careful reading of Scripture. To construct a durable and biblically faithful theology, some deconstruction often has to take place. This can be a painful, confusing time, but the student who perseveres will come away knowing not only what to do as a pastor and how to do it, but also why they believe what they do. That strong belief, hard-won through prayer and the wrestling of careful reflection, will undergird a ministry that lasts a life-time. Like a weight-lifter, muscle must be broken down before it can be built back up, stronger and more resilient in the process. When applied to Christian faith, this is the sacred task of theological education, a task that is sometimes called “constructive theology.”

Graduates of the ITN Diploma in Theology program, Bukavu, DRC

Though theological educators walk alongside students who are coming to understand what they believe and why, the process is not without boundaries. Dr. Thomas Noble has noted that theologians are first and foremost “theologians in service to the church” (Global Nazarene Theology Conference, Guatemala, 2002). They hold in-trust the church’s doctrinal heritage, helping reproduce it in the next generation of its clergy. For this reason, teachers of Bible, theology, church history, Christian ethics and related disciplines are carefully vetted and continually responsible to both fellow educators and church leaders who offer guidance and (when necessary) censure. Well has it been said: “While orthodoxy is not a straight line, it is a fenced-in area.” At the same time, the church must give leeway and space to theological educators, allowing them the academic freedom to carry out their calling in creative ways, always adjusting their methods to fit the changing needs of changing times, yet simultaneously maintaining the underlying integrity of “the faith that was once for all entrusted to God’s holy people” (Jude 1:3, NIV).Now more than ever, when it comes to raising up the next generation of leaders in the church, we need both training and theological education. Our pastors must know what to do and how to do it, but let us also remember the “why.” Only when we give students space – exercising patience and trusting God the Holy Spirit to guide them as they make the Christian faith their own both in heart and mind – will we reap the long-term benefit of strong clergy equipped to lead a strong church into an uncertain future.

------------------------

* Thank you to Anita Henck, for pointing me to Simon Sinek’s idea.

Gregory Crofford | April 12, 2015 at 3:41 pm | Tags: ministerial training, theological education | Categories: Christian theology in Africa, Church & Discipleship | URL: http://wp.me/p1xcy8-1cm

____________________________

No comments:

Post a Comment