AMY GOODMAN: A federal jury in Oregon Thursday acquitted antigovernment militia leaders Ammon and Ryan Bundy, and five of their followers, of conspiracy and weapons charges related to their armed takeover of a federal wildlife refuge earlier this year. The stunning verdict shocked federal prosecutors, who called the 41-day occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge a lawless scheme to seize federal property by force. This is the Bundys’ attorney Matt Schindler, followed by one of the defendants, Neil Wampler.

MATTHEW SCHINDLER: It was a very powerful thing to have individuals with nothing come and fight the federal government in this building, rely on nothing more than the truth, and prevail.

NEIL WAMPLER: We simply have to keep on trucking here and build on the tremendous victory that has occurred here today for our rights and for rural America.

AMY GOODMAN: The occupation forced federal employees onto administrative leave, cost the federal government over $4 million, alarmed local residents. It also angered the Paiute Tribe, which has treaty rights to the land the militia occupied. The tribe says militia members mishandled tribal artifacts, bulldozed sacred sites. Militia leaders Ammon and Ryan Bundy still face federal charges related to an armed standoff in Nevada in 2014.

Joining us now to discuss the Bundy verdict in light of the ongoing protests in North Dakota, how the two were handled so differently, are Kieran Suckling, executive director of the Center for Biological Diversity—he is joining us from Tucson—and Steve Russell, a retired judge and professor, and citizen of the Cherokee Nation. His latest piece for Indian Country Today Media Network is "Malheur v. DAPL: Jury Nullification or Prosecutor Overreach?"

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Steve Russell, let’s go first to you in Austin. Talk about what’s happened in this verdict, the acquittal of the Bundy brothers, and what’s happening in North Dakota, why you wrote about them together.

STEVE RUSSELL: Well, I think you, of all people, who might have wound up being a defendant, would understand that the water protectors maybe headed in the same direction. They may have to ask a jury to do justice—that is, to go past the law and do the right thing. That’s what we call jury nullification. You can find many legal scholars who have a lot of scorn for that, but it exists, and it has to do with things other than all-white juries turning the Klan loose after they’ve killed somebody.

AMY GOODMAN: What was your reaction to the acquittal of the Bundy brothers?

STEVE RUSSELL: Well, it appeared to me that most of the elements of the crime were on video. I’m down here in Texas. All I know is what I saw. But I don’t know what the jury saw. And since I’m a judge, I’m really reluctant to criticize a jury verdict without having sat there and watched the evidence. I can imagine a poor presentation of the case, but I can’t assume there was a poor presentation. It could have been the jury having their little sagebrush rebellion, or it could have been a poor presentation. I can’t tell.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, in this case, in the case of what took place in Oregon, there’s no question of the—this was an armed militia. They proudly displayed their weapons.

STEVE RUSSELL: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: Compare it to North Dakota.

STEVE RUSSELL: Well, in North Dakota, the Standing Rock people are saying, "Please come, please help us, but leave your weapons at home." We’ve been through this before. We went through this with what we call Wounded Knee II, where there were actions taken to try to defend tribal lands, but they were violent actions, and that didn’t work out too well. And speaking of which, I keep thinking back to Wounded Knee I, the last great massacre of the Indian Wars in 1890. Those people were coming from Standing Rock. And here we are. It just blows my mind.

AMY GOODMAN: Kieran Suckling, you were in Oregon at the time. You went to the standoff. You’re with the Center for Biological Diversity in Arizona. Talk about what you saw in Oregon and your reaction to the acquittal.

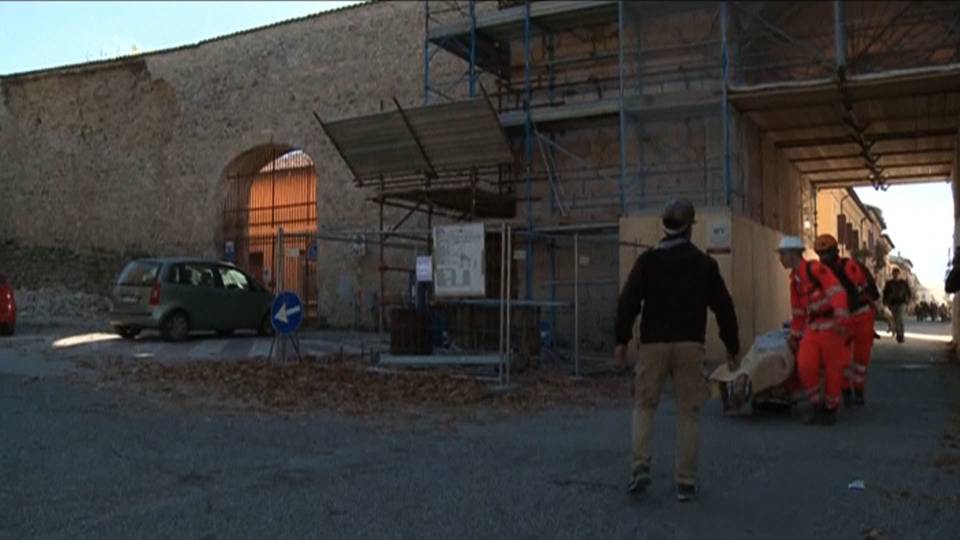

KIERAN SUCKLING: Yeah, I went up to the occupied site while the militia was there to counterprotest them. And it was an extraordinary scene—you know, 50, 60 armed men running around with assault rifles, like blatant racism wherever you would go, you know, threats to kill the feds, threats to kill myself and other protesters who were there. It was a very, very belligerent, violent group.

So, when the verdict came down and they were acquitted of all crimes, I was—I was shocked. I was—I was devastated. And it really made me afraid for our public land managers throughout this country, who now are going to be threatened more by these militia forces, emboldened by this verdict.

AMY GOODMAN: Why do you think they were acquitted, Kieran?

KIERAN SUCKLING: I think it was a jury nullification. I think that the prosecutor had a difficult time convincing the jury that these were armed, dangerous people, when the FBI had allowed them free rein to come and go from the compound for 41 days, to travel interstate, to get mail delivery, to get food delivery. And surely, the jury was like, "Well, I don’t understand. The FBI treated them like royalty, and now you’re telling me that they’re armed criminals." I think that led the jury to just say, "We don’t care whether they’re guilty or not."

AMY GOODMAN: Kieran, talk about—

KIERAN SUCKLING: Even presented as nice white Christians.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about your relationship with the Bundys and the work you’ve done for nearly two decades in Nevada, in Utah and now Oregon.

KIERAN SUCKLING: Yeah, I mean, this whole battle started in 2014 when the Bundy clan had a different armed standoff with the BLM over cattle grazing down there. And we were fighting the Bundys over that, because they had refused to pay their grazing fees, they were damaging Native American sites. And so, having, in their mind, succeeded in holding off the feds with guns there, they then proceeded to go to Utah, to a place called Recapture Canyon, and go in there with guns. This is a very sacred Native American site, that was closed down, car access, to protect it. And the Bundys went in there and tried to create an armed standoff. They failed to incite the government there, so then they moved on to Oregon. I mean, this is a group of armed men seeking revolutionary standoffs with the federal government, going from state to state to state.

AMY GOODMAN: And compare how they’re dealt with by the government, by the police, by the FBI, with how the Native Americans are dealt with at Standing Rock. We’ve seen the images—

KIERAN SUCKLING: Well—

AMY GOODMAN: —of the armored personnel carrier, of the LRAD, the sound cannons, military equipment, a fully armed riot police squad that are the sheriff’s deputies, that are called in from all over to deal with these Native Americans and their allies who are fighting this pipeline.

KIERAN SUCKLING: Yeah, I mean, the difference is incredible. I mean, these men, in 2014, had an armed standoff with federal agents, pointed rifles at them, and then were allowed, free, for two years, to go and promote other armed standoffs. They get to Oregon, and they were allowed, for 41 days, to come and go for that compound. They weren’t stopped. Their water was supplied. The mail line was kept open. The electricity was kept open. They could travel interstate to promote more insurrection. It’s just incredible to see what happens if you’re white and you’re associated with ranching, how you can do what you want, whereas peaceful Native American protesters are just brutalized immediately by the police.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, what message do you think this sends in Oregon? What are your concerns right now, Kieran, and why this is so important to you, why you’ve gotten involved with this issue for these decades?

KIERAN SUCKLING: Well, the message is loud and clear that armed men with guns are going to be allowed to go and take the public land that belongs to all Americans. They’re going to be allowed to go and destroy Native American sacred sites with impunity. And this verdict is essentially open season on our public lands, on the people that go and manage those public lands. And it’s created a very dangerous, volatile and, I think, fundamentally racist situation.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Kieran Suckling, I want to thank you for being with us, from the Center for Biological Diversity, speaking to us from Tucson, Arizona, and Steve Russell, retired judge and professor, citizen of the Cherokee Nation, speaking to us from Austin, Texas.

To see our interview on what’s happening right now in Morocco, a nation that’s risen up over the killing of a fish seller this weekend, you can go to democracynow.org.

[WEBINAR] Talk Brain Health - November 2 from National Alliance for Caregiving of Bethesda, Maryland, United States "Let's Talk Brain Health! from the National Alliance for Caregiving for Monday, 31 October 2016

[WEBINAR] Talk Brain Health - November 2 from National Alliance for Caregiving of Bethesda, Maryland, United States "Let's Talk Brain Health! from the National Alliance for Caregiving for Monday, 31 October 2016