Lausanne Global Analysis: Venezuela, North Africa, Korea, and Beyond of the Lausanne Movement for Friday, 14 September 2018

The September 2018 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis is now available!

Read the Issue Overview

Connecting influencers and ideas for global mission

SEPTEMBER 2018 ISSUE OVERVIEW

DAVID TAYLORWelcome to the September issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, which is also available in Portuguese and Spanish. We look forward to your feedback on it.

In this issue we examine Venezuela’s descent from wealth to despair and how Christians can respond to the country’s populist disaster; we consider the ‘Walking with Jesus Movement’ that seeks to respond to the crisis in the Korean church resulting from the challenges of secularisation; we analyse the lessons we can learn from the ‘vanished church’ in North Africa including the need for unity in diversity; and we address the global phenomenon of shame and how Christ is the answer.

‘The recent history of Venezuela represents the unfolding of a Faustian tragedy’, writes Wolfgang Fernandez (Director of Next Step). A nation with immense resources, whose people have lived as if there were no end to the party, now finds itself with some of the most complicated problems of any country. Most Venezuelans basically just try to survive, and an unprecedented exodus has ensued. As Venezuelans are scattered, new opportunities arise for them to be used by the Lord to bless the nations. Also, expatriates are privately sending food, emergency supplies, and funds back to support their families and others. The crisis has enabled others who have courageously chosen to stay in the country to explore fresh ways to bring hope to a broken people, starting with groups of believers that model the values of the kingdom of God. We need to equip our Venezuelan brothers and sisters to meet needs, giving hands and feet to the gospel. The nation desperately needs food and humanitarian aid but also the salt and the light of the kingdom. There is a lot of work to do, and we need the global community to assist them practically and to pray for people of peace to arise. ‘With prophetic fervor, we must broadcast everywhere the atrocities that are being carried out in this country; and with merciful hearts, let us work together with our Venezuelan brothers and sisters, to bring renewed hope to their nation’, Fernandez concludes.

‘The Korean church has achieved tremendous quantitative growth since the 1980s, but there has been too little focus on qualitative growth’, write Kisung Yoo (senior pastor of Good Shepherd Church in Seungnam, Korea) and Paul Sung Noh (missionary and mission scholar). An inability to find Christlikeness is at the heart of the Korean church’s crisis today and is the reason why the Walking with Jesus Movement (WJM) movement began. WJM, which is growing rapidly in Korean and other Asian churches, aims for people to live every moment with a sense of God’s presence and to enjoy intimacy with the Lord in daily life. WJM uses the spiritual journal as the key tool to develop a sense of presence and intimacy with the Lord. The use of information technology in keeping the journal allows people to communicate with others in cyberspace. WJM can be an answer for the global church to the challenges of secularization. It is astonishing news that Christians in Seoul, who live in a highly developed and secularized metropolitan city, have experienced living with the presence of Jesus and enjoying an intimate walk with him in their daily lives. As a first step, WJM sought to renew Korean churches and help them to overcome their moral and spiritual crisis. It has now spread to Japan, China, Taiwan, and Indonesia. In the long run, we are confident that it will spread to quench the spiritual thirst and hunger of numerous churches around the world. ‘We are working to enable the blessings of WJM to become available to the global church’, they conclude.

‘At one point, the largest cities in the Roman empire were, besides Rome, Alexandria in Egypt and Carthage in present-day Tunisia’ write Mons Gunnar Selstø (missionary with Norwegian Lutheran Mission) and Frank-Ole Thoresen (President of Fjellhaug International University College, Norway). These cities also became strongholds for the Christian church. Early Christian thinkers, such as Tertullian, Cyprian, and Augustine, were all born in North Africa and served in Carthage. With such a proud history, one might be puzzled by the outcome of the Arab expansion in the region, from the seventh century onwards. Many scholars have battled with the question of why the church could not withstand the new masters. During the 300 years leading up to the Arab expansion in the region, two separate churches had been established, and the divide between the two was growing. They would stigmatize each other as false, and efforts at unity always failed. This division highlights an important tension between the church as a global, and as a local, contextualized entity. Furthermore, several studies have demonstrated how religious conversion and the religious development of various groups have often been inter-related with greater socio-political and ethno-political dynamics. Experiences of ethnic and cultural marginalization may play a significant role in strengthening the ethnic identity of a group, in opposition to the dominator. The history of the Berber population in North Africa follows this pattern, which has also been identified in various other contexts, including in modern times. ‘Churches worldwide might gain from embracing a “unity in diversity”’, they conclude.

‘Social media have given everyone a megaphone, and reputations can be destroyed in seconds with a viral tweet. As a result, we are all becoming more sensitive to shame and its power’, writes Simon Cozens (missionary with WEC International). When we feel ashamed, we want to hide and put a distance between ourselves and the situation or people that shamed us. We cannot remove the shame from ourselves; so, we remove ourselves from the source of the shame. Baptism as death and rebirth is a powerful image for those whose old life carries the burden of shame. Furthermore, shame is a problem of community; it happens because I am deriving my identity from the people around me. You might not be able to change the opinions, but you can certainly change the people—as well as putting the old self to death, baptism is also the gateway to a new community, the community of the people of God. The gospel gives us a new society, a new family, and in our new family we are accepted without shame. We can see from this that the church itself has a key part to play in God’s solution for shame. Christ gives a brand new life to the person suffering from shame; the church gives them a brand new arena in which to live. ‘When these two things come together, real freedom is possible’, he concludes.

We hope that you find this issue stimulating and useful. Our aim is to deliver strategic and credible analysis, information and insight so that as a leader you will be better equipped for the task of world evangelization. It’s our desire that the analysis of current and future trends and developments will help you and your team make better decisions about the stewardship of all that God has entrusted to your care.

Please send any questions and comments about this issue to analysis@lausanne.org. The next issue of Lausanne Global Analysis will be released in November.

Grouping: Lausanne Global Analysis

The Lausanne Movement

The Lausanne Movement connects influencers and ideas for global mission, with a vision of the gospel for every person, an evangelical church for every people, Christ-like leaders for every church, and kingdom impact in every sphere of society. Learn about our beginnings, ongoing connections, and mission today. Learn More- About

- Our Mission

- Our Legacy

- Get Involved

- Billy Graham & John Stott

- Leadership

- Blog

- News Releases

- Email Updates

- Privacy Policy

- Contact Us

- Missional Content

- The Lausanne Covenant

- The Manila Manifesto

- The Cape Town Commitment

- Lausanne Global Analysis

- Best Of Lausanne

- Bookstore

- Lausanne Occasional Papers

- Videos from Gatherings

- Consultation Statements

- Cape Town 2010 Advance Papers

- Cape Town 2010 Global Conversation

- Lausanne Global Classroom

- Search all Lausanne Content

- Connections

- Issue Networks

- Regions

- Generations

- How to Connect with Lausanne

- Gatherings

- Upcoming Gatherings

- All Gatherings

- Younger Leaders Gathering 2016

- Cape Town 2010

- Manila 1989

- Lausanne 1974

Understanding the nation's pain and awakening hope

Wolfgang Fernandez

Venezuela represents the unfolding of a Faustian tragedy. A nation with immense resources, whose people have lived as if there were no end to the party, now finds itself with some of the most complicated problems of any country.There are important lessons to be learned here, as Venezuela has gone from a nation of great wealth to one of even greater despair.

In 1976, I left Venezuela to study theology in Toronto, inspired by listening to former Lausanne Associate René Padilla in Caracas to dedicate my life to world evangelisation. I never went back to live in my native country. As I worked in over 60 countries, I seldom, if ever, met a Venezuelan living outside the country—that is, until the last couple of years.

Descent into chaos

After the Second World War, Venezuela experienced an unprecedented economic boom. Oil wealth created a new environment in which money flowed freely and the nation quickly modernized. At the same time, a sense of ease and a ‘why worry’ attitude prevailed at all levels of society. Most foods were cheaper to import than to grow and process locally, despite the abundance of productive land.In 1999, leftist populist Hugo Chávez became president with broad support, offering promises of social justice and equitable distribution of wealth. At first, he addressed major issues like housing, education, and health care, but soon he turned to building his own personal ‘Bolivarian dream’. He built up the military while warning of an impending ‘Yankee’ invasion. Infrastructure projects failed and proved to be fertile ground for widespread corruption.

In 2008, the price of oil collapsed. Chávez’s promises began to reveal a lack of coherent planning, and he was unable to bring the nation to its real potential. He died unexpectedly in 2013.

Chávez, like many Venezuelans, followed a mixture of Spiritism and Catholicism (in that order). He performed a ritual exhuming the bones of the Liberator Simon Bolivar through which he sought to claim his spirit and power. Now officials openly speak of Chávez as if he were still alive. He is venerated—his image is often placed on altars next to or above Jesus Christ.

His handpicked successor, Nicolás Maduro, took over. Under his stewardship, the country has degenerated into seemingly endless chaos. Maduro has responded to the myriad problems it faces by hardening his authoritarian position and repressing any kind of protest. In May, he conducted a highly controversial election in which the majority of the population refused to vote despite his inducements. Yet Maduro took it as his mandate.

Exodus

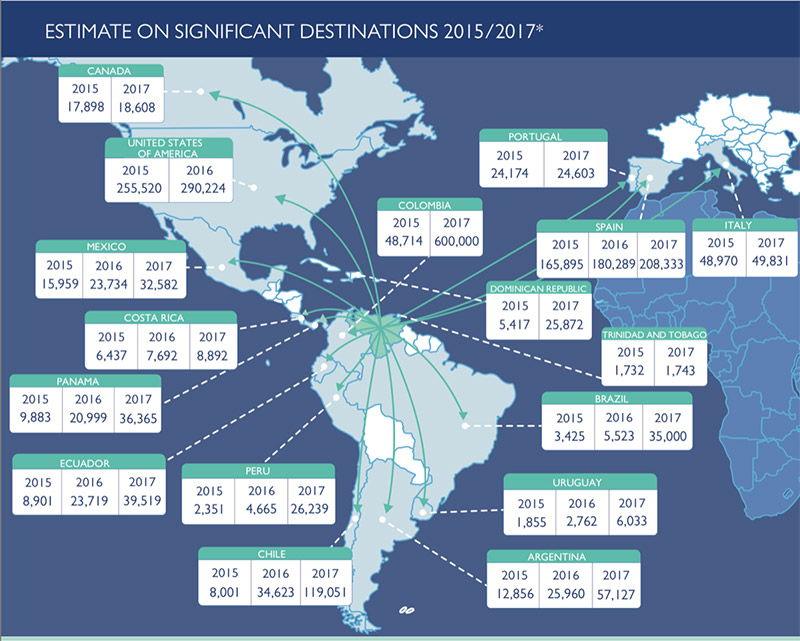

Most Venezuelans are now ‘burned out’ as they basically just try to survive, and an unprecedented exodus of Venezuelans has ensued. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), some 1,642,442 left the country between 2015 and 2017.[1]

They leave in desperation because the food supply has collapsed. The government has reduced imports by 75 percent, instead choosing to use its hard currency to pay off the national debt. Since medicine has also traditionally been imported, the cuts have severely limited the availability of medicine too. Venezuela is in the midst of a medical crisis. HIV/AIDS, Malaria, Dengue Fever, and other diseases are on the rise. At the same time, there has been an explosion of criminal violence that has seen homicide rates far higher than in Baghdad and Kabul and also an alarming increase in cases of sex trafficking.

Doing good while scattered or staying

Like myself, Venezuelans in the diaspora have found themselves in a new situation where our culture, resourcefulness, and humour have brought an interesting contribution to our new home countries. For example:Lawyers, architects, and economists find themselves selling clothes in markets in Lima, working as nannies cleaning houses in Santiago de Chile and working in restaurants in Bogota.

Gustavo Dudamel, the acclaimed director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, has made Venezuela known in positive ways.

Pastor Ramon Mendoza relocated first to Panama and now Mexico City, and serves as Latin America Director for Dynamic Church Planting International.

As our people are scattered, new opportunities arise for missions and for Venezuelans to be used by the Lord to bless the nations.

In our own family, we already have members living in ten nations; yet the majority are still in Venezuela. Some have put their faith in Jesus, others have not. All must deal with the difficult realities every day of just finding food and medical care.

By way of further example, Angel Rafael Arellano is an Industrial Psychologist who left an influential and successful career and is now in Bogota seeking to establish himself once again. There is a significant number of people like him who need the assistance and support of the local church, enabling them to bring a vital contribution to their new homes.

Yet, the crisis has also enabled others who have courageously chosen to stay in the country to explore fresh ways to bring hope to a broken people.

One of my many cousins, Pastor Abihail Lara, serves in Colonia Tovar. He sees that the internal situation now is far more complex than it often seems from the outside. For example:

Inflation is estimated by the IMF to be the highest in the world at 13,000 percent this year.[2]

There is no cash and the banking system is regularly interfered with by the government.[3]

The instability has resulted in constant insecurity, with 30 percent of the population unemployed and some 87 percent now living below the poverty line.

Efforts to bring hope to Venezuela

These pressures are forcing Christian ministries to think of new ways to impact people’s daily lives, starting with groups of believers that model the values of the Kingdom of God.

One model that seeks to live out this new perspective of service is developing in Pastor Lara’s community, La Colonia Tovar. Nexus, a new social enterprise engaging in agricultural projects together with local leaders, is growing fast crops and raising chickens and pigs, resulting in substantial blessings. The community of believers is expanding, demonstrating that help can come from inside the country.

However, since many have left, there is a need to train new leaders with willing hearts to serve holistically. This moved Pastor Lara to create another entity, Hagios, an online ministry for theological formation[4]:

Hagios is equipping pastors, who have a calling for theological education, to train others without pulling them out of their communities where their neighbours need them.

It is the first indigenous Venezuelan theological training program and reaches into various contexts where traditional training programs do not exist.

From any smart device a pastor or leader can access the Hagios platform and be trained without having to leave home.

The Hagios Team

Hagios has also started a project for growing ‘Hagios communities’: small groups of online students who meet face-to-face seeking to find ways to influence their social and church environments.Among expatriates, several people have initiated food drives and emergency items collections and are privately shipping them to Venezuela. The government is allowing this while openly rejecting offers of help from the US and EU. Others are able to send funds back from outside to support their families. The amounts are quite significant.

Our family’s contribution is been implemented in partnership with Nexus , the enterprise Pastor Lara has established. We have raised funds in the US to buy prime land which is being used to grow fast crops of nutritious vegetables. Funds have also been raised to build pig and chicken houses. These products are being used to feed the local community of believers and their needy neighbours. A portion is also being sold in the open market as a means to generate revenue for seed, although cash is useless as the inflationary trends make prices go up every day.

Agriculture has never been a priority in Venezuela. At this time more people are turning to it but the soil is generally fallow. A great deal of soil repair must be carried out. Organic technologies are desperately needed to make this viable.

How to bless Venezuela

The best strategy to awaken the ways of the Kingdom of God in Venezuela is to equip people to meet needs, giving hands and feet to the gospel. There is no question that the nation desperately needs food and humanitarian aid. Yet, while we meet immediate needs, we must encourage the men and women of God who are suffering the same adversities to acquire a new awareness of service and commitment to modeling Jesus in all dimensions of society, so that they may be the salt and the light for which Venezuela is longing (Matt 5:13-15).

As a Venezuelan, I know that I am not alone; there are many others leading efforts to meet needs from the outside. The best results are being achieved relationally, drawing minimum attention.

There is a lot of work to do and we need the global community to assist us practically wherever possible and to pray for people of peace to arise. Globally, we must own the pain of the Venezuelan people as much as we share the pain of injustice and inequality everywhere. With prophetic fervor, we must broadcast everywhere the atrocities that are being carried out in this country; and with merciful hearts, let us work together with our Venezuelan brothers and sisters, to bring renewed hope to their nation.

How to respond to Populism

In light of the emergence of populist political leaders globally, we must recognize the pitfalls and opportunities for the gospel. Populist leaders such as Chávez, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Donald Trump in the United States, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and also the leaders of Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and most recently Italy, seem generally to end up pitting people against each other. These leaders have given a voice to groups that feel marginalized and powerless, but they also seek to use them to gain power. The re-emergence of Populism is resurrecting demons we thought were buried at the end of the Second World War.

Harvesting the produce for distribution

Populists often pin present troubles on those who are easily caricatured as the embodiment of society’s woes. The easiest targets are immigrants, refugees, and minorities of all types. These people represent the very ones Jesus taught us to care for as a demonstration of the mercy and love of the Father. It is important to recognize that it is often the failure of Christians to set a tone of compassion which has left society without a clear sense of guidance as to how to deal with the others in our midst.Populist leaders see that gap, but, instead of solving the problem, they use the problem to present themselves as ‘saviors’. We as people of the Kingdom must recognize that the demagoguery of Populism is incapable of delivering solutions and instead serves only to further polarize societies. We must repent of our sin of indifference and prejudice and eagerly seek to embrace those who are targeted by Populists.

The 65 million refugees globally represent a massive opportunity that we must embrace and creatively seek to accommodate in our communities.[5] By modeling reconciled communities we could answer the questions no one else is answering.

Endnotes:

- Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, http://robuenosaires.iom.int/sites/default/files/Informes/National_Migration_Trends_Venezuela_in_the_Americas.pdf. ↑

- International Monetary Fund, http://www.imf.org/en/Countries/VEN. ↑

- Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-03/venezuela-orders-arrest-of-eleven-executives-from-banesco-bank. ↑

- Hagios, http://hagios.tk/. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Cindy M. Wu entitled, ‘When We Too Were Strangers’, in the May 2018 issue of Lausanne Global Analysishttps://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2018-05/we-too-were-once-strangers. ↑

Overcoming the challenges of secularization

Kisung Yoo & Paul Sung Noh

Korean churches are facing a crisis; and a discrepancy between faith and life is one of the main causes. The Korean church has achieved tremendous quantitative growth since the 1980s, but there has been too little focus on qualitative growth. It has failed to encourage members to living a distinctive lifestyle, and the salt lost its saltiness. Inconsistency between faith and life has become the main reason for Christians leaving their faith and the church. This inability to find Christlikeness is at the heart of the Korean church’s crisis today and is the reason why the Walking with Jesus Movement (WJM) movement began.

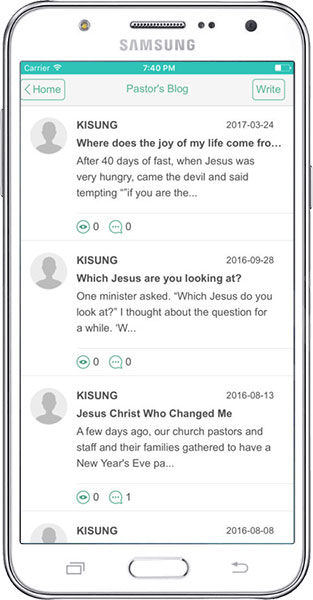

WJM is a rapidly growing movement in Korean and other Asian Churches. WJM aims for people to live every moment with a sense of God’s presence and to enjoy the intimacy with the Lord in daily life. Because of its quintessential purpose and its use of cyberspace, it can be seen as a 21st-century cyber monastery movement.

Rev Kisung Yoo, Senior Pastor,

Good Shepherd Church,Seoul

This movement was started by Rev Kisung Yoo, the senior pastor of Good Shepherd Church in Seoul. He asserts that it is possible for believers to experience the presence of the Lord 24 hours a day in their normal mundane life and to enjoy intimacy with him. He uses the spiritual journal as a tool to develop the sense of presence and intimacy with the Lord. Keeping a spiritual journal every day is the most crucial part of the WJM.WJM origins

Rev Yoo’s belief stems from his own special spiritual experience. It started when he read Frank C. Laubach’s Prayer Diary. Frank Laubach was born in 1884 and was a missionary in the Philippines for 45 years. He did not feel spiritual satisfaction in spite of his long religious life and wondered if ‘living every moment with a sense of God’s presence and feeling its intimacy’[1] were possible.

Then, in 1930, he submitted himself to feeling the presence of God in every moment for one year. After six months of spiritual experiment, he succeeded in grasping God’s presence in each moment. He said, ‘I resolved that I would succeed better this year with my experiment of filling every minute full of thinking of God than I succeeded last year.’[2]

Prayer Diary by Frank C. Laubach

Challenged by Laubach’s spiritual experience, Rev Yoo and his wife, Rebecca Park, conducted a full-scale experiment to sense the presence of the Lord 24 hours a day and feel intimacy with Jesus for a month in 2009, using his sabbatical month.During the whole month, they gazed upon Jesus from morning until evening and tried to sense the presence of the Lord. Then they wrote how they experienced the Lord in daily life in a diary. This simple writing was the beginning of a spiritual journal. Through the experiment, they started to feel the presence of the Lord deeply and built up intimacy with the Lord that endures to this day. The experience of dwelling in the Lord gave them a tremendous security in the Lord, and resulted in remarkable changes in their lives:

In my youth, I was challenged by the truth that Jesus lives in me. Since that time, the desire for this amazing truth has grown stronger and stronger, constantly seeking and searching for the Lord in me. I began to write a spiritual journal during the journey. Through Frank Laubach, I realized how important it is continually to look upon Him. Looking at Jesus, I have walked with Him at home, at work, and in everyday life and experienced the Lord intimately.[3]

Spiritual journal

Rev Yoo shared his experience with his church members. He developed the spiritual journal into a spiritual development program. The spiritual journal is a simple record of how one thinks about and experiences Jesus in daily life, following four guideline questions in the form of a prayer or a diary:- When do you think of Jesus in a day?

- How do you feel when you think of Jesus in a certain situation and what happens or changes when you acknowledge him?

- What special things can you remember during the day and how did Jesus work at those moments?

- What has happened when you obeyed (or disobeyed) the promptings of Holy Spirit (Jesus) given to you?

The spiritual journal has faced criticism from some from a conservative theological background that it does not emphasize the objectivity of the Word of God and that its subjectivity slides into mysticism. However, Rev Yoo is adamant that the Word of God is at the core of the spiritual diary. Some critics also express concern about dualism, the separation of life and spirituality, suggesting that it leads to a lack of social participation, like medieval mysticism. However, this is also a misunderstanding of WJM. The spiritual diary aims to change Christians’ lives as they accompany the Lord in their daily activities.

IT importance

A key factor in the growth of the WJM movement was the building of a website and creating a journal writing app. The using of IT in keeping the journal allows people to communicate with others in cyberspace:Chatrooms in cyberspace group four to seven people.

They can share their daily life with the Lord beyond time and space limitations.

The spiritual diary app has also changed the quality of the small group meetings. Because small group members share their everyday life using the app, they can have deeper fellowship in the group. It thus functions as a monastery in cyberspace.

Korean church crisis

Korean churches are facing falling numbers and a wider crisis. Futurist Choi Yunsik has said:

The feast of the Korean church is over. Not only are Korean churches in spiritual stagnation, but, much worse, they are plummeting. If we do not renew our efforts to cut the bones [work very hard], an 8.7 million Christian population in 2005 will be reduced to 3 or 4 million by 2050, and Sunday schools will be reduced to 300-400 thousand[4].

Korean churches, which experienced a remarkable revival in the last century, are facing a crisis because they have failed to raise disciples who can live the life of Jesus in Korean society:

- The media is full of stories of sexual and financial scandals involving pastors and other Christians.

- They built large church buildings and gathered many crowds, but their lifestyle was not different from the world.

- The inability to find Christlikeness is at the heart of the Korean church’s crisis today and is the reason why the WJM movement began.

An answer to the challenges of secularization

These problems afflict churches outside Korea too. Asian and other churches have experienced a sharp decline in numbers and a spiritual crisis in the face of secularization. Francis Chan, as a representative of Western Christians, issued a powerful warning to Chinese Christians at the first ‘Mission China Conference’ in Hong Kong in 2015 not to follow the path of the Western Churches, which are losing their spiritual power due to secularization.The WJM movement can be an answer for the global church to the challenges of secularization. It is astonishing news that Christians in Seoul, who live in a highly developed and secularized metropolitan city, have experienced living with the presence of Jesus and enjoying an intimate walk with him in their daily lives.

It is possible to build up Christlikeness in a Christian’s life by living in the presence of the Lord amid a secular society, where money, sex, power, and other personal desires are competing for one’s attention. The spiritual diary is key to this:

The problem of the Korean church is that the pastors neglect the right relationship with Jesus while caring only for the right knowledge of Jesus. We have a lot of knowledge about Jesus. However, it is really shameful that there is no intimacy with Jesus. Korean Christians suffer from spiritual thirst because they do not have intimacy with the Lord. Then they can easily fall into Satan’s temptation of money, sex, and power. The only way to defeat this temptation is to stand on Jesus Christ only. We should not stay in the stage of knowing Jesus well. Rather we should reach the stage of enjoying close and intimate relationship with the Lord. That is why we must continue to develop our sense of knowing the presence of the Lord[5].

By doing this, the WJM movement is also pursuing the original essence of the Christian faith. It is a core teaching that Christ is incarnated and dwells in us. Establishing right relationship with Jesus Christ who dwells in Christians and seeking intimacy with him are the essential means of enjoying our salvation.

It is easy to find movements which sought the presence of the Lord and intimacy with him in early church history. Notably, the monastic movement pursued intimacy with the Lord. David Brainerd, John Wesley, and George Muller used spiritual journals as tools for practising companionship with the Lord. The WJM is not that different from them, but it can be much more effective because of its use of technology.+

Growing influence

Since the spiritual diary app was launched in November 2010, over 900 churches and 70,000 people in 137 countries have joined the movement. On average, 40,000 people are sharing their journal each day, and journal writers are continuing to grow.Rev Yoo’s book, The Spiritual Journal, is now published in Korean, English, Japanese, Chinese, and Indonesian, with Spanish and Portuguese to follow. The WJM occasionally holds spiritual journal conferences, sharing ideas on practical spiritual life and how to walk with Jesus. There have been 20 such conferences in Korea and Asian countries including Taiwan, China, Indonesia, and Japan at the request of churches there.

Now the WJM is developing multilingual websites and apps for the spiritual journal, enabling foreign users such as English and Chinese to write their spiritual diary easily[6].

Outlook

As the first step, the WJM movement sought to renew Korean churches and help them to overcome their moral and spiritual crisis. It has now spread to Korea, Japan, China, Taiwan and Indonesia. In the long run, we are confident that it will spread from Korean and Asian regions to quench the spiritual thirst and hunger of numerous churches around the world.

Implications

The WJM is a fundamental movement of Christianity that seeks the presence of, and intimacy with, Christ in a Christian’s daily life. The spiritual journal, in particular, provides an excellent tool of spiritual discipline that enables Christians to walk with Christ in a secularized society. We are working to enable the blessings of the WJM to become available to the global church.

Specifically, the WJM hopes to serve the global church in cooperation with leaders in the Lausanne Movement. We invite advice and cooperation from Lausanne leadership in order to plan to serve the global church together. We strongly believe that our own journey and experience could be used as a tool to serve thousands of churches worldwide for the glory of Our Lord.

Endnotes:

- Renovare, https://renovare.org/articles/living-each-moment-with-a-sense-of-gods-presence-frank-laubach ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Kisung Yoo, The Spiritual Journal, (WJM Resource), 2. Author’s translation. ↑

- Yunsik Choi, Future Map of Korean Church 2040, 39. Author’s translation. ↑

- Yoo, The Spiritual Journal, 1. Author’s translation. ↑

- Diary with Jesus, http://en.diarywithjesus.com/home?lang=en, Journal with Jesus, http://en.journalwithjesus.org/home?lang=en. ↑

Embracing a theology of 'unity in diversity'

Mons Gunnar Selstø & Frank-Ole Thoresen

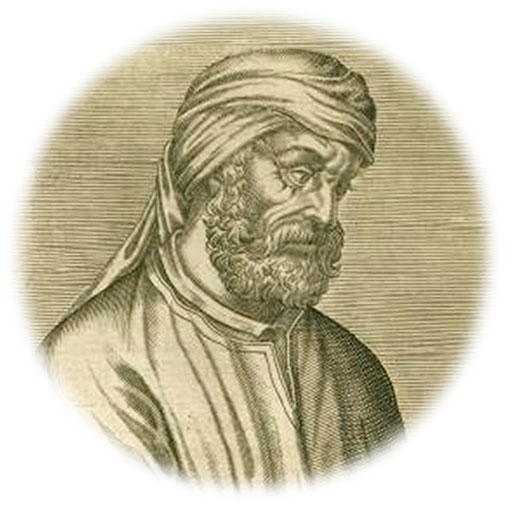

The story of how the early church expanded through Asia Minor and found a foothold in Europe is common knowledge. However, the story of how it expanded on the opposite side of the Mediterranean through North Africa is less well known. At one point, the largest cities in the Roman empire were, besides Rome, Alexandria in Egypt and Carthage in present-day Tunisia.These cities also became strongholds for the Christian church. Early Christian thinkers, such as Tertullian, Cyprian, and Augustine, were all born in North Africa and served in Carthage. With such a proud history, one might be puzzled by the outcome of the Arabic expansion in the region, from the seventh century onwards. Many scholars have battled with the question of why the church could not withstand the new masters.

There are several factors that might form part of the answer. However, we have singled out two that might also have something to teach us in our time:

- The fact that it might be misleading to speak of one church. During the 300 years leading up to the Arab expansion in the region, two separate churches had been established, and the divide between the two was growing. They would stigmatize each other as false, and efforts at unity always failed. This division highlights an important tension between the church as a global, and as a local, contextualized, entity.

- Native resentment towards foreign rulers and their religious identity. The local Berber population apparently chose a ‘religion of difference’—alternative church affiliation played into a national Berber identity and political opposition.

Augustine and the Donatists

Contextualization or unity?The Donatist movement, which gained a foothold among the Berbers, arose after Christianity became the official Roman religion. The Catholic Church remained politically and culturally faithful to the Roman empire, while the Donatist Church would represent a more nationalistic ecclesiastical movement. It was shaped by the indigenous Berber community. It took a firm and conservative dogmatic stance, but incorporated a more charismatic form of expression. The Donatist Church took pride in its African heritage, Tertullian’s teaching on radical discipleship and the purity of Christian life, and its identity as a martyr church.

Tertullian

The Catholic Church, on the other hand, emphasized the universality of the church, Tertullian’s teaching on church unity, and its servanthood to society. It worked eagerly to adapt to a new status as the church of the Roman Empire.The conflict between the Catholic and Donatist churches may thus be considered to represent the tension between the church as a global and a local entity, and the Donatists were considered a threat to the unity of the church.[1] It featured:

a religio-political tension between the ‘global’ Romanized church and the church as a contextually integrated faith; and

a tension between uniformity of language and expression, and the need to maintain a local Christian identity.

However, for present-day missionary work, we may ask whether unity needs to imply organizational unity and Christian cultural uniformity. Perhaps the missionary should rather encourage a ‘unity in diversity’,[2] where cultural characteristics are stimulated and not seen as a hindrance to Christian unity.

We should also pay greater attention to the Donatist Church’s history when we speak of the North African church—not the least because the Donatist Church remained in place in the face of the Muslim expansion, while the Catholic Church fled.

Further, we are tempted to imagine with L.R. Holme:

If the Church had only succeeded in getting hold of the great mass of the Berber tribes, if it could only have enlisted under the banner of Christ all the enthusiasm that afterwards supported the cause of Islam, it might well have been that not only would the Saracens have never succeeded in crushing African Christianity after the conquest of the province, but they might never have conquered the province at all. As it was, the teaching which appealed strongly to the Berber mind was condemned by the leaders of the Church as imperfect, and those who taught and believed it were subject to the ban of the ecclesiastical and secular authorities.[3]

Although it may sometimes be painful for those involved in missions when an indigenous church seeks separation and independence, or establishes practices that are unfamiliar and foreign, yet, the modern missionary should ask whether the church is simply coming of age.

Church between cultural center and periphery

The Berbers were traditionally nomadic and remained largely a rural group. They were never tempted by the culture of the cities, which was strongly influenced, and dominated by the Roman immigrants and their cultural heritage. Berber societies were organised according to tribal structures, inherently opposing the Roman-controlled, centralized state.Over the centuries, the cities in North Africa increasingly became administrative centers, populated by the political, financial, military, and religious elite. The Catholic Church, Latin language, and the Roman way of living dominated in every aspect. Thus, the Berbers, although representing the indigenous population and constituting the ethnic majority, remained culturally peripheral, lacking influence as well as political, financial, and cultural representation.

Several studies have demonstrated how religious conversion and the religious development of various groups have often been interrelated with greater socio-political and ethno-political dynamics, and, accordingly, must be interpreted through such frameworks.[4]

Experiences of ethnic and cultural marginalisation may play a significant role in strengthening the ethnic identity of a group, in opposition to the dominator.

The history of the Berber population in North Africa follows a recognizable pattern in this regard. When the Roman occupying power discouraged and persecuted Christians during the first three centuries, surprisingly, Christianity found a foothold and thrived among the Berber population. Later, after the Catholic Church became the religion of the state from the year AD 380, the Berbers turned from the Catholic Church to Donatism, and persecution continued. Thus, religious following and religious identity continued to constitute an element of opposition to foreign rulers in the area throughout this considerable timespan.

A similar pattern has been identified in various other contexts, including in modern times. One such example is the history of religious development in parts of Eastern Africa. Several studies have demonstrated how opposition to the historically dominant group, the Orthodox Christian Amhara people, played a significant part in forming the religious fabric of present-day Ethiopia[5]:

- As the Amhara colonized western and southern parts of the country, the religious composition of the area changed.

- However, most ethnic groups did not embrace Orthodox Christianity. They rather turned to alternative interpretations to the religion of the colonizers.

- The numerically strong and spiritually vibrant Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus, for instance, has a majority of members from the ethnic Oromo population who experienced persistent cultural marginalization under Amhara rulers.

Furthermore, it may indicate that God is at work in shifting conditions, and that God relates to us as people of cultures and societies. It is therefore interesting to note that a similar dynamic may be taking place in the North African region at present:

The number of Arab Christian believers are few.

However, for several years, there have been regular reports of quite a few Berbers turning to Christianity in North Africa.[6]

It is noteworthy that David Garrison, for instance, emphasizes the impact of employing the Berber language among the Christians, as opposed to the official program of Arabization and suppression of traditional Berber culture.[7]

Further Lessons for the Contemporary Church

Every cross-cultural missionary brings with him or her a heritage, regarding both theology and culture. Often the two may be difficult to distinguish, since religion is also an integral part of culture. Accordingly, no missionary is culturally unbiased, and our gospel message tends to carry cultural predispositions. There is no difference in this regard, whether our theological and cultural heritage is Korean, Nigerian, or Norwegian. A simple reproduction of our church heritage in other cultures may well become an ‘ecclesiological imperialism’, where we, perhaps unwittingly, impose our tradition on others. We should rather ask ourselves what part of our message is indispensable, and what is not.

Cross-cultural missionaries also need to consider the aspects of political, financial, and power representation. Being cultural outsiders, there is no ‘neutral space’. We always represent something. Although we may not be able to remove such representation, the missionary should be attentive to it, and seek to counteract the influence of such elements. Otherwise we may contribute to alienating the church from its context.

The trailblazer of twentieth-century missiology, Paul Hiebert, championed the importance of ‘self-theologizing’.[8] Every young church needs to develop a contextual theology, one that makes cultural sense and gives answers to questions of cultural relevance. Missionaries should encourage such a development, even if the local leaders may not always reach the same conclusions as would the missionary. This may be a painful process, as the history of the Berber church has emphasized. However, it may also be a process of growth for the missionary, as our church heritage is challenged and may develop further in dialogue with new perspectives.

Churches worldwide might gain from embracing a ‘unity in diversity’. In the contemporary Western world, this challenge is just as valid with regard to emerging immigrant churches in their midst. The ‘majority churches’ of the West must consider how they can relate to the new immigrant churches in such a manner that the influx of Christians from the Global South may make a positive contribution towards reinvigorating and reinterpreting Christianity in the West.[9]

Endnotes:

- Chris J. Botha, “The Extinction of the Church in North Africa,” in Journal of Theology for Southern Afrika 57 (December 1986): 24-31. ↑

- Harding Meyer, That All May Be One: Perceptions and Models of Ecumenicity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 93. ↑

- L. R. Holme, The Extinction of the Christian Churches in North Africa, 1st Edition 1898 (Leopold Classic Library, 2016), 253. ↑

- Øyvind M. Eide, Revolution and Religion in Ethiopia. The Growth and Persecution of the Mekane Yesus Church 1974-1985 (Oxford: James Currey Ltd, 2000), 15-22, 85-93. ↑

- Hassen Mohammed, The Oromo of Ethiopia. A History 1570-1860 (Cambridge, 1990), 77. Arne Tolo, Sidama and Ethiopian. The Emergence of the Mekane Yesus Church in Sidama. Studia Missionalia Upsaliensia (LXIX. Uppsala, 1998), 279-82. ↑

- Bruce Maddy-Weitzman, “The Berber Awakening” in The American Interest, Volume 6, Number 5 (1 May 2011), and similarly David Garrison, A Wind in the House of Islam: How God is Drawing Muslims Around the World to Faith in Jesus Christ (Colorado: Wigtake Resources, 2014), 81-98. ↑

- Ibid., 93-94. ↑

- Paul G. Hiebert, Anthropological Insights for Missionaries (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1985), 193-224. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Sam George entitled, ‘Is God Reviving Europe through Refugees?’, in May 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysishttps://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-05/god-reviving-europe-refugees. ↑

Read or Listen

Kyoko learnt to think of herself as below those around her. She made friends with other burakumin, but she was always careful around people she did not know. She did not feel like she really fit in; everywhere she went she carried a sense of shame.

When Kyoko first heard about God, she wondered why God had made her a burakumin. However, as she learnt about how Jesus ‘emptied himself’ and ‘became nothing’, she came to believe in a God who loved buraku and non-buraku Japanese equally. She has been set free from her shame.

Ronson gives the examples of Justine Sacco, the American PR executive who was publicly derided on the Internet after an ill-advised joke which ‘ruined her life’[2], and Adria Richards, who faced a public backlash after shaming two computer developers behaving inappropriately at a conference.

Here in Australia, one Melbourne man found his ‘name smeared’ after a false accusation about him was shared thousands of times on Facebook.

Social media have given everyone a megaphone, and reputations can be destroyed in seconds with a viral tweet. As a result, we are all becoming more sensitive to shame and its power[3].

Typical reactions to shame

Roberto (again, not his real name) moved to Australia from South America twelve years ago. He speaks reasonable English with a strong Hispanic accent, although his children sound just like their Australian friends. Some time ago he suffered racist abuse from co-workers at the school where he worked, and not long after reporting it to the management and going through a process of arbitration, he found himself terminated and is now unemployed. He feels ashamed of his language, his inability to provide for his family, and the isolation he has endured as a foreigner.

Some friends tried to share the gospel with him, but the idea of God taking away his sin did not resonate at all—he sees himself not as a sinner, but as sinned against! What is the gospel for Roberto?

Let us first listen to what Roberto and Kyoko said about their situations. ‘I felt like I wanted to disappear’. ‘I just want to stay in the house and never go out’. ‘I felt like it would be better if I had not been born’. These, according to psychologist Michael Lewis, are classic reactions to the feeling of shame and humiliation. When we feel ashamed, we want to run away, to hide, to put a distance between ourselves and the situation or people that shamed us. We cannot remove the shame from ourselves; so we remove ourselves from the source of the shame. If we are shamed by our society, then we remove ourselves from society.

Günter Seidler describes the experience of shame as the desire ‘to remain invisible or in extreme cases to be extinguished’[4]. Figuratively speaking, we drive the shameful person into non-existence; we put the person who was shamed to death. Ronson writes about how the victims of Internet shaming talk about themselves as being ‘destroyed’, ‘annihilated’ and ‘killed’[5].

In some countries, this is more than just a metaphor. In Japan, an individual who is shamed or humiliated will often remove himself from society through self-imposed ostracism or even suicide. Around 20,000 – 30,000 Japanese people choose to end their own lives every year. The reasons are naturally varied, and Japan’s relative lack of access to mental health services means that clinical depression is not dealt with in the same way as in the West. However, among the complex web of reasons for suicide, financial and job-related worries seem to be most common. Financial failure or loss of employment, leading to a feeling of being unable to provide for one’s family, brings a sense of shame that can be impossible to bear.

In the Middle East, too, the solution to shame is sometimes found through death. On 16 March 2008 in Iraq, Rand Abdel-Qader was stabbed to death by her own father. Her brothers helped to kill her and throw her into a pit, while her uncles stood around to spit on her corpse. She had brought shame on her family by talking with a British soldier, and the only way to restore the family’s honour was for her shameful body to be removed from society.

In the Middle East, too, the solution to shame is sometimes found through death. On 16 March 2008 in Iraq, Rand Abdel-Qader was stabbed to death by her own father. Her brothers helped to kill her and throw her into a pit, while her uncles stood around to spit on her corpse. She had brought shame on her family by talking with a British soldier, and the only way to restore the family’s honour was for her shameful body to be removed from society.

Baptism as death and rebirth

When we share a gospel of sin being forgiven and relationship being restored, we often assume that someone’s life just needs patching up a little. Jesus takes away your sin, and you go on living. However, if we look at the gospel that Paul preached, we find something far more radical: you have died. Your life up until this point is over. When you went down into the waters of baptism, you were united with Christ in his death. When you came up out of the water, you were united with Christ in his resurrection and given a new life and a new identity. Christ gives the shamed person exactly what they long for—the gift of death.

Baptism as death and rebirth is a powerful image for those whose old life carries the burden of shame. In fact, it always has been: between the second and fourth centuries, converts to Christianity were baptised naked. Cyril of Jerusalem explains the link between nakedness, baptism and the removal of shame:

As soon, therefore, as you enter in, you put off your garment; and this was an image of putting off the old man with his deeds. Having stripped yourselves, you were naked; in this also imitating Christ, who hung naked on the Cross, and by His nakedness spoiled principalities and powers, and openly triumphed over them on the tree. You were naked in the sight of all, and were not ashamed; for truly you bore the likeness of the first-formed Adam, who was naked in the garden and was not ashamed.[6]

The church as God’s solution

However, how does dying and being reborn spiritually help Roberto and Kyoko practically? Roberto is still unemployed. Kyoko is still a member of an outcast group.

The answer is that shame is a problem of community; it happens because I am deriving my identity from the people around me, just like Adam and Eve who took their eyes off their Maker and had their eyes opened to one another. Shame is only a problem for me because of the opinions of my peers, my in-group, and the people I care about. You might not be able to change the opinions, but you can certainly change the people: as well as putting the old self to death, baptism is also the gateway to a new community, the community of the people of God.

Norman Kraus, a former missionary to Japan, wrote that when dealing with shame, ‘the changed pattern of relationships is an essential part of the gospel of salvation itself’[7]. The gospel does not just change who we are, but it gives us a new society, a new family, and in our new family we are accepted without shame.

This is why it is so important for the people of God to avoid playing the shame game, and to relate to one another by God’s standards, not by the world’s. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians is full of warnings about the dangers of factionalism, judgment, and comparison in the Christian community. Instead, he replaces these things with the image of one body, working together, the weaker members indispensable, and the more shameful members treated with special honour.

We can see from this that the church itself has a key part to play in God’s solution for shame. Christ gives a brand new life to the person suffering from shame; the church gives them a brand new arena in which to live. When these two things come together, real freedom is possible.

Kyoko has now become a missionary in India, where she helps another group of ‘untouchables’ to see that Jesus is not ashamed of them. Roberto is still not yet a Christian, but he has found a group of Christian men that he continues to journey with—men who do not see his employment status or immigration status, but see him as he really is, as a bearer of the image of God.

Feature image from ‘THE “ETA 穢多”, “BURAKUMIN 部落民”, and “HININ 非人” – The Non-Human Outcasts of Old Japan‘ Source: Okinawa Soba (Rob) (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Simon Cozens is a missionary with WEC International. After seven years as a church planter in Japan, he taught at a missionary training college in Tasmania for three years before returning to the UK. His book, Looking Shame in the Eye, will be published by InterVarsity Press in the middle of 2019.Read or Listen

Simon Cozens is a missionary with WEC International. After seven years as a church planter in Japan, he taught at a missionary training college in Tasmania for three years before returning to the UK. His book, Looking Shame in the Eye, will be published by InterVarsity Press in the middle of 2019.Read or Listen

How the gospel transforms the untouchable to the touched-by-grace

Simon Cozens

Her only fault was that she was born in the wrong part of town. Because of the district in Japan where Kyoko (not her real name) came from, she was considered a ‘burakumin’, one of the ‘untouchables’. Hundreds of years ago, these districts were home to leatherworkers, tanners, gravediggers, and other professions considered unclean to Japanese society. Even today, people from the outcast areas can suffer discrimination in their search for jobs, housing, and marriage partners. It is not uncommon for parents to use private investigators to check out the background of their children’s intended partners, and for matches to be called off if a buraku link is discovered.Kyoko learnt to think of herself as below those around her. She made friends with other burakumin, but she was always careful around people she did not know. She did not feel like she really fit in; everywhere she went she carried a sense of shame.

When Kyoko first heard about God, she wondered why God had made her a burakumin. However, as she learnt about how Jesus ‘emptied himself’ and ‘became nothing’, she came to believe in a God who loved buraku and non-buraku Japanese equally. She has been set free from her shame.

So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed

by Jon Ronson

Online shaming

Kyoko’s experience is, of course, not unique to Japan. After I left Japan and moved to Australia, I realised that similar dynamics of shame, humiliation, and rejection are everywhere. Jon Ronson, who wrote a book entitled, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, about the phenomenon of online shaming, believes that we are ‘at the start of a great renaissance of public shaming’[1]:Ronson gives the examples of Justine Sacco, the American PR executive who was publicly derided on the Internet after an ill-advised joke which ‘ruined her life’[2], and Adria Richards, who faced a public backlash after shaming two computer developers behaving inappropriately at a conference.

Here in Australia, one Melbourne man found his ‘name smeared’ after a false accusation about him was shared thousands of times on Facebook.

Social media have given everyone a megaphone, and reputations can be destroyed in seconds with a viral tweet. As a result, we are all becoming more sensitive to shame and its power[3].

Typical reactions to shame

Roberto (again, not his real name) moved to Australia from South America twelve years ago. He speaks reasonable English with a strong Hispanic accent, although his children sound just like their Australian friends. Some time ago he suffered racist abuse from co-workers at the school where he worked, and not long after reporting it to the management and going through a process of arbitration, he found himself terminated and is now unemployed. He feels ashamed of his language, his inability to provide for his family, and the isolation he has endured as a foreigner.

Some friends tried to share the gospel with him, but the idea of God taking away his sin did not resonate at all—he sees himself not as a sinner, but as sinned against! What is the gospel for Roberto?

Let us first listen to what Roberto and Kyoko said about their situations. ‘I felt like I wanted to disappear’. ‘I just want to stay in the house and never go out’. ‘I felt like it would be better if I had not been born’. These, according to psychologist Michael Lewis, are classic reactions to the feeling of shame and humiliation. When we feel ashamed, we want to run away, to hide, to put a distance between ourselves and the situation or people that shamed us. We cannot remove the shame from ourselves; so we remove ourselves from the source of the shame. If we are shamed by our society, then we remove ourselves from society.

Günter Seidler describes the experience of shame as the desire ‘to remain invisible or in extreme cases to be extinguished’[4]. Figuratively speaking, we drive the shameful person into non-existence; we put the person who was shamed to death. Ronson writes about how the victims of Internet shaming talk about themselves as being ‘destroyed’, ‘annihilated’ and ‘killed’[5].

In some countries, this is more than just a metaphor. In Japan, an individual who is shamed or humiliated will often remove himself from society through self-imposed ostracism or even suicide. Around 20,000 – 30,000 Japanese people choose to end their own lives every year. The reasons are naturally varied, and Japan’s relative lack of access to mental health services means that clinical depression is not dealt with in the same way as in the West. However, among the complex web of reasons for suicide, financial and job-related worries seem to be most common. Financial failure or loss of employment, leading to a feeling of being unable to provide for one’s family, brings a sense of shame that can be impossible to bear.

Baptism as death and rebirth

When we share a gospel of sin being forgiven and relationship being restored, we often assume that someone’s life just needs patching up a little. Jesus takes away your sin, and you go on living. However, if we look at the gospel that Paul preached, we find something far more radical: you have died. Your life up until this point is over. When you went down into the waters of baptism, you were united with Christ in his death. When you came up out of the water, you were united with Christ in his resurrection and given a new life and a new identity. Christ gives the shamed person exactly what they long for—the gift of death.

Baptism as death and rebirth is a powerful image for those whose old life carries the burden of shame. In fact, it always has been: between the second and fourth centuries, converts to Christianity were baptised naked. Cyril of Jerusalem explains the link between nakedness, baptism and the removal of shame:

As soon, therefore, as you enter in, you put off your garment; and this was an image of putting off the old man with his deeds. Having stripped yourselves, you were naked; in this also imitating Christ, who hung naked on the Cross, and by His nakedness spoiled principalities and powers, and openly triumphed over them on the tree. You were naked in the sight of all, and were not ashamed; for truly you bore the likeness of the first-formed Adam, who was naked in the garden and was not ashamed.[6]

The church as God’s solution

However, how does dying and being reborn spiritually help Roberto and Kyoko practically? Roberto is still unemployed. Kyoko is still a member of an outcast group.

The answer is that shame is a problem of community; it happens because I am deriving my identity from the people around me, just like Adam and Eve who took their eyes off their Maker and had their eyes opened to one another. Shame is only a problem for me because of the opinions of my peers, my in-group, and the people I care about. You might not be able to change the opinions, but you can certainly change the people: as well as putting the old self to death, baptism is also the gateway to a new community, the community of the people of God.

Norman Kraus, a former missionary to Japan, wrote that when dealing with shame, ‘the changed pattern of relationships is an essential part of the gospel of salvation itself’[7]. The gospel does not just change who we are, but it gives us a new society, a new family, and in our new family we are accepted without shame.

This is why it is so important for the people of God to avoid playing the shame game, and to relate to one another by God’s standards, not by the world’s. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians is full of warnings about the dangers of factionalism, judgment, and comparison in the Christian community. Instead, he replaces these things with the image of one body, working together, the weaker members indispensable, and the more shameful members treated with special honour.

We can see from this that the church itself has a key part to play in God’s solution for shame. Christ gives a brand new life to the person suffering from shame; the church gives them a brand new arena in which to live. When these two things come together, real freedom is possible.

Kyoko has now become a missionary in India, where she helps another group of ‘untouchables’ to see that Jesus is not ashamed of them. Roberto is still not yet a Christian, but he has found a group of Christian men that he continues to journey with—men who do not see his employment status or immigration status, but see him as he really is, as a bearer of the image of God.

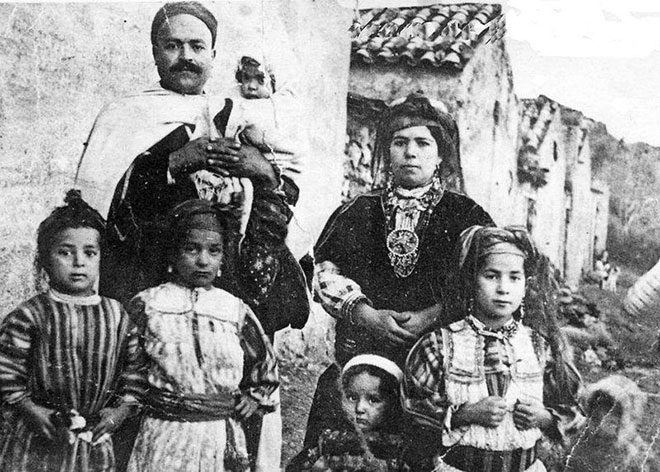

Untouchables of India, Malabar, Kerala (1906).

Endnotes:- J. Ronson, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (London: Picador, 2015), 9. ↑

- Ibid., 69. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Jayson Georges entitled, ‘The Good News for Honor-Shame Cultures’, in the March 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis. https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-03/the-good-news-for-honor-shame-cultures. ↑

- G. H. Seidler, G H, In Other’s Eyes: An Analysis of Shame (Madison, CT: International Universities Press, 2000), 207. ↑

- Ronson, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, 175. ↑

- Cyril of Jerusalem, Mystagogical Cathecisis II – On the Rites of Baptism, 59-60. ↑

- C. N. Kraus, Jesus Christ Our Lord: Christology from a Disciple’s Perspective (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1990), 241. ↑

Feature image from ‘THE “ETA 穢多”, “BURAKUMIN 部落民”, and “HININ 非人” – The Non-Human Outcasts of Old Japan‘ Source: Okinawa Soba (Rob) (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Lausanne Global Analysis seeks to deliver strategic and credible information and insight from an international network of evangelical analysts to equip influencers of global mission. Browse all the past issues at lausanne.org/lga. The publication of the LGA is overseen by its Editorial Advisory Board. Articles represent a diversity of viewpoints within the bounds of our foundational documents. The views and opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the personal viewpoints of Lausanne Movement leaders or networks. Inquiries regarding the Lausanne Global Analysis may be addressed to analysis@lausanne.org.

***

No comments:

Post a Comment