Alban Weekly from The Duke Divinity School in Durham, North Carolina, United States "PRACTICAL WISDOM FOR LEADING CONGREGATIONS: Staying Put: A Look at the First 10 Years of Ministry" for Monday, 12 September 2016

Staying Put: A Look at the First 10 Years of Ministry

Staying Put: A Look at the First 10 Years of MinistryDuring my years in parish ministry I offered spiritual direction for clergy in the area. In the span of two years, four pastors came to me with what seemed to be the same symptoms. Each felt a sense of restlessness, malaise, and vague anxiety about the future of his or her current congregational ministry. Puzzled that their struggles seemed so similar, I looked for a common factor in these pastors' lives and their widely differing church contexts.

The only common element all four shared was the length of time they had served their current parishes. Each was in either the seventh or eighth year with one congregation. Moreover, none of these pastors had previously stayed with one parish for more than five years. Could this common thread of short pastoral tenure be the source of their restlessness?

After informal surveys, as well as conversations with pastors and denominational staff, I'm convinced that important dynamics are at work in a pastor's tenure at one church. In my view, a particular pattern marks the pastor's first 10 years in one parish. The pattern is shaped by several elements:

First, the dynamics of the corporate relationship inform how a pastor is called or appointed to a church, begins his or her ministry there, and moves into the role of pastoral leadership.

Second, the pastor's unique relationship with a congregation manifests itself in a predictable ministerial life cycle. The existence of such a cycle suggests that a pastor's experience in the parish can be anticipated and managed.

Read more from Israel Galindo »

Staying Put: A Look at the First 10 Years of Ministry

During my years in parish ministry I offered spiritual direction for clergy in the area. In the span of two years, four pastors came to me with what seemed to be the same symptoms. Each felt a sense of restlessness, malaise, and vague anxiety about the future of his or her current congregational ministry. Puzzled that their struggles seemed so similar, I looked for a common factor in these pastors’ lives and their widely differing church contexts.

The only common element all four shared was the length of time they had served their current parishes. Each was in either the seventh or eighth year with one congregation. Moreover, none of these pastors had previously stayed with one parish for more than five years. Could this common thread of short pastoral tenure be the source of their restlessness?

After informal surveys, as well as conversations with pastors and denominational staff, I’m convinced that important dynamics are at work in a pastor’s tenure at one church. In my view, a particular pattern marks the pastor’s first 10 years in one parish. The pattern is shaped by several elements. First, the dynamics of the corporate relationship inform how a pastor is called or appointed to a church, begins his or her ministry there, and moves into the role of pastoral leadership. Second, the pastor’s unique relationship with a congregation manifests itself in a predictable ministerial life cycle. The existence of such a cycle suggests that a pastor’s experience in the parish can be anticipated and managed.

First Year: “Which Door Does This Key Open?”

For most clergy, the first year at a new church is filled with excitement and challenge. You work to get to know the members (who’s who, who does what and, if it’s a small congregation, maybe even who’s related to whom). This “getting to know you” phase is accomplished by providing basic pastoral care, visiting with members, and meeting with as many church groups as possible. You blunder through discovering the “turf” that people think belongs to them, and you manage to put out a few fires—mostly issues neglected during the interim between “settled” pastors.

During the honeymoon, you work at understanding the church’s history, listening for stories that define the congregation’s personality and identity. The early months offer the perfect opportunity to “get dumb” and ask questions that you won’t be able to get away with later. Taking an “observer” stance in the first year of ministry at a new call or appointment allows you to discover the church’s rhythms, habits, and practices.

In the first year, ministry management consists of giving attention to basic pastoral and leadership functions—fixing failed administrative practices, for example. These often are simple inconveniences for which no one has taken responsibility. During the first weeks at my first executive position, I was puzzled that one of the secretaries would occasionally peek into my office and say, “Dr. Galindo, a box was just delivered. Where do you want it?”

My immediate thought was, “It’s just a box. Put it anywhere!” But I realized that what the secretary really wanted was an administrative decision. The question had less to do with where to put the box than it did with the system’s relief that someone was on board whose job it was to make decisions.

During your first year you may tinker with the worship service—but don’t tamper with it! Most churches will allow the “new” minister some leeway in tweaking the worship service. After all, they know you went to seminary, and they assume you know a little about worship and liturgy. But most ministers seem too eager to make major overhauls of worship—usually, regrettably, informed more by personal preference than by theology. Making too many changes in the worship service threatens a primary source of corporate identity, and the wise pastor will patiently take time to observe which worship practices are important to the congregation’s identity before tampering with the liturgy.

During your first year in a parish, three other ministry management details are critical. First, negotiate a fair salary package with the church, and open a retirement account. Second, get into the habit of reading all those books you didn’t finish in seminary. It’s amazing how many clergy stop reading after seminary—and it shows in their sermons! Third, find a support group; it may make the difference between thriving in ministry and suffering early burnout.

Second Year: Extend the Honeymoon

In your second year, the honeymoon is about over, so enjoy it and try to extend the goodwill. With one year’s routines under your wing, you know what’s coming next as the year rolls on. Now you can anticipate what’s around the corner in the life of the church; you can plan ahead and make wise changes.

Now you can anticipate problems and make changes to address them. Realize, however, that most of these changes will be administrative—fixing procedures already in place that are broken, streamlining current practices for efficiency and effectiveness, shoring up existing structures, and promoting better communication and integration in church ministries and organization. Basically you’ll be addressing people’s points of anxiety and solving difficulties and inconveniences. But if you try to make essential changes, you’ll likely run into quick resistance and sabotage.

The truth is that organizations and people don’t like to be changed—regardless of what they may say or ask for. Some parishioners are beginning to get to know you, and most members will take your lead with caution. Remember, they’ve seen pastors and staff come and go. At this stage, they don’t expect anything different from you. One pastor told of this experience:

I instituted a major program during my first two years at the church, and I’ll never forget what one good deacon said to me: “I hope this is the right thing for us to do because, remember, I was here long before you got here, and I’ll be here long after you’re gone.” Meaning: “Don’t leave us with something that’s going to mess us up, or that we’ll have to live with.” Guess what? He was right! I’m gone and he’s still there.

During your second year at the church, people aren’t ready to make changes that challenge the ways they relate, think, or function. Remember, some of them have learned that all they need to do is wait you out! They’ve seen staff come and go, and they’re not yet willing to invest emotionally in you or your ideas—no matter how logical, rational, or appropriate they may be. The wise pastor who is restless for “change” will find ways to make high-profile, low-risk changes.

Ministry management in your second year should involve writing a case study of your church. By now you know enough about the church and its people to begin to understand the congregation. Categorize the church in terms of its congregational size, stance, and style. Size is an important indicator—but not because bigger is better, or because a larger church is “more real” than a small one.1 Size, while having no theological significance for the congregation’s effectiveness, is a determinative factor in faith formation. The nature of group formation and the way people relate to one another help “shape” the faith of those who are part of the group. The congregation’s size gives “shape” to its members. Understanding that dynamic will help you know what pastoral leadership to provide.

Determine your church’s stance—how it views its mission and ministry. Often a congregation’s stance is determined by its immediate context, as with the urban ministry church, the university church, the country club church, or the community church.

Sometimes a church’s stance is determined by theology, as with the mission church, the pillar church, the shepherd church, or the outreach church. Understanding the congregation’s stance will put you in touch with its values, myths, self-identity, vision, and practices.

Determine your church’s style. By style, I mean the kind of corporate spirituality your church embraces. Basic congregational spirituality styles include the head, heart, pilgrim, mystic, servant, and crusader spiritualities.

Writing such a case study will help you begin to shape and articulate a vision for your ministry tenure in this congregation. Note that the vision to be worked on at this stage concerns your ministry. The vision you will develop for the congregation comes later. Get clear about yourself first, before you attempt to shape a vision for your congregation.

Third Year: Hitting Your Stride

During your third year of ministry you’re feeling comfortable with your role. You know what needs to be done, and you know how to do it. You’ve gotten to know some of the people in your congregation, and you have some “fans” among them.

By your third year you have a clear enough idea of the parish and have gathered enough information to begin pondering what needs to be addressed in the life of the church. But heed this caution: The more clearly you make known the direction in which you want to lead the church, the more creative the resistance and sabotage will become. The wise pastor knows not to take such resistance personally, understanding that change is hard for churches.

If you are a new pastor, and have survived your first pastorate so far, you will have learned more about yourself and about church than you learned in seminary—or than you are likely to learn for most of your remaining ministry years. Why? The learning curve is steep in these first three years. And since what you need to learn is directly correlated with your survival, the learning is meaningful and powerful. Authors Michael and Deborah Jinkins point out that the quantity of new demands placed on beginning pastors correlates positively with their level of competence. Most pastors will not reach a “comfort zone” where ministry demands and competence meet until well into their third year.2

During your third year at a church, ministry management involves decisions about your stewardship of ministry. To organize the leadership functions that you will provide from now on, decide how you will invest your time and talents—on what and in whom. The demands on your time and attention seem endless, and they come from a myriad of sources. You can spend your ministry attending to problems, peccadilloes, the art of keeping people happy, the management of conflict (or the perpetual avoidance of it), and any number of other tasks that, in the end, will never yield lasting results or encourage maturity and growth in your congregation. Or you can realize that you are human and have limited personal resources—and can decide to invest yourself only in those people and ministries that will make a difference in the long run.

Fourth Year: The Year of Discontent

Something happens to most of us during our fourth year at a church. We get restless. Not uncommonly, we find ourselves sitting in the office, looking out the window, and wondering what other ministry opportunities may lie ahead of us. The fourth year is often a time of low energy. Problems at the church that were previously a challenge have become merely a nuisance; we suspect that we may be solving the same problems over and over. During this year of malaise and ennui, you may, “just in case,” update your résumé and keep it on your personal computer’s hard drive.

One hazard faced by many pastors at this point: they may start paying the price for their lack of study and purposeful work in personal growth and professional development. If all you have is a bag of tricks, you may start running out of surprises to pull out of the bag (and believe me, some parishioners will notice). This malaise and lack of purpose may explain, at least in part, the phenomenon of pervasive turnover of parish pastors before the five-year mark.

Ministry management during “the winter of our discontent” involves recapturing the passion of your calling amid the details and drudgeries of ministry’s administrative side. Now is the time to recommit yourself to reading books and journals, learning new ministry skills, and retooling for the next stages of pastoral leadership. For beginning clergy, it’s a good time to consider formal continuing education—perhaps entering a good doctor of ministry program. Seminaries require three years of ministry experience for applicants to their D.Min. programs, and for good reason—by that time new clergy are ready to learn things they were not ready to hear during their seminary tenure.

Fifth Year: The Latency Year

For most pastors the fifth year of ministry seems to be a latency year. People begin to trust you; some even like you. By now, a core group of members has come to love you. You begin to make your mark as the neighborhood pastor and find your niche in your local professional network. Having handled most administrative problems and basking in the renewed good will of a less anxious congregation, you coast a bit. You initiate creative programs or ministries and institute challenging changes. Because you enjoy by now a certain level of congregational trust, these are accepted with little resistance.

Ministry management in the fifth year includes renegotiating your salary, if you haven’t already. Many clergy are so eager to be called to a church that they are unrealistic in assessing the financial impact of a move. By now you have a more realistic idea of your personal or family financial needs. Don’t do the church a disservice by neglecting to help the board or finance committee understand the realistic financial costs of calling and keeping a good staff.

If your church does not have a sabbatical leave policy, now is the time to begin educating the congregation as to its value. Take the initiative in making possible a dialogue that will create a sabbatical leave policy.3 At the same time, inventory your personal ministry skills so that you can sharpen the competencies you’ll need for the next stage of ministry.

Sixth Year: Ministry Redirection

As several elements converge in the sixth year of ministry, it may become a time of ministry redirection. If you are a staff member in your sixth year at a church, the senior pastor has probably left by now. The new demands on you to function at higher levels of leadership make ministry challenging, exciting—and scary. Your job may include “breaking in” the interim pastor and, eventually, the new senior pastor.

During this year it’s not uncommon for both pastor and staff members to rework their résumés. Some begin considering serious inquiries from other churches, perhaps even paying a visit or two at the invitation of a search committee. This temptation to accept a new call may signal that the ministry groove you’ve created is becoming a ministry rut. It’s time to begin asking yourself questions about essential changes in your ministry leadership roles and professional goals. Will you stay in the parish ministry for the rest of your working years? Do you want to go into teaching? Will you specialize, perhaps in pastoral care and counseling? If you are an associate or assistant minister, will you seek a sole or senior pastor position? If you are a sole pastor, will you take on the challenges of leading a multiple staff? Is it time to move on to a bigger church?

Ministry management in the sixth year can include an episode of housecleaning. Start throwing out clutter—the dated stuff that has accumulated on your desk, in your files, in your library, in the church organizational structures, and in the church buildings. By now you know whether you

can throw out that ugly blue flower vase in the sanctuary without incurring the wrath of a member whose great-aunt Alice donated it. Since you know enough about “personal” and “public” territories in your church, you can safely start throwing out junk that has accumulated around the church buildings over the years. But perhaps the most important ministry management you’ll do in the sixth year is to explore seriously your sabbatical options. Be mindful, however, that as you begin to plan your sabbatical you’ll likely encounter some sabotage—from yourself and from the congregation. You’ll both develop a certain level of separation anxiety. Tell yourself that this reaction is natural. Don’t let it stop you from benefiting from an important resource for you and your church.

Seventh Year: Recharge or Burnout?

If you serve on a pastoral staff, the new senior pastor is probably on board by now. Your new boss will either take up the church’s vision and support your philosophy and approach to ministry, or will want to bring in his or her own vision of ministry. It’s time to call the district office, update the résumé, and perhaps even put out some “feelers.” If you and the new pastor have meshed and you decide to stay on, you’ll need to renegotiate your relationship and leadership function with the church.

If you’re the pastor, you’ll probably find yourself saying, “I can’t believe it’s been seven years!” And if you’re anything like those four pastors who came to me for spiritual direction, you’ll start feeling some stirrings that will blossom full-blown next year.

As for ministry management in your seventh year, it’s time for your sabbatical. Take it—no matter what.

The Eighth Year: The Pivotal Year

If you have made it to the eighth year of ministry in your congregation and decide to stay, something fascinating and powerful happens. You’ll feel an emotional shift in your relationship with your congregation—and the members will feel it also. In your eighth year you’ll notice that a whole generation of children who have grown up in the church are beginning to leave. You’ll find yourself officiating at the funerals of people who are now friends—not just “church members.” Perhaps for the first time, you’ll begin to understand what the metaphor of “pastor” really means.

At this point you will realize that the people in your congregation are the products of your ministry, and you’ll wonder what difference you are making. This realization is powerful, and it can be overwhelming.

This shift in the pastoral relationship is what drove those four ministers to seek help. All four intuitively sensed that they and their ministries were on the verge of something different and new. They were in touch with the notion that staying in their respective places of ministry, regardless of the context, would require a new way of relating and ministering. For some, the prospect of entering into a more intimate relationship with their congregations was frightening. For others, standing on the border of uncharted territory aroused fears about their competence.

Ninth Year: The Year of Commitment

If you navigate successfully the relational and emotional shifts of the eighth year, you can make an emotional commitment to your congregation. You settle comfortably into the realization that this is your church and your home. You belong here. Your congregation, meanwhile, senses whether you are staying or going, and will respond accordingly.

Your relationship with the congregation now undergoes a definite shift. It becomes deeper, more honest, more intimate, and more vulnerable. As a result of this shift, ministry becomes more about relationships and less about management. And it is that shift, I believe, that so frightened the four pastors who came to me. Ministry as management is easy, really. Clergy training does fairly well in equipping pastors for the management of ministry. But the heart of ministry, like the heart of the gospel, is not management but relationship. And having a more intimate relationship with people is more frightening than standing behind the façade of professionalism and competence in “managing” people. Tragically, too few clergy are able to make the shift. Too many seem willing to abort the possibility of a long tenure at one congregation, opting instead for the safety of minister-as-manager in a string of short-term pastorates.

Tenth Year: Ministry Begins

If you have lasted up to the tenth year and have invested well in your tenure of ministry, you and your congregation share a mutual relationship of trust, a shared corporate identity, and a common vision of ministry. Your relationship with the congregation can provide the resources to begin working on whom you can become. Because your pastoral leadership function will take on new directions, now is the time to quit recycling sermons. More important, now is the time to begin thinking about the life of this congregation two or three generations into the future.

Now is the time your ministry begins.

—————

NOTES1. See Alice Mann, The In-Between Church: Navigating Size Transitions in Congregations (Bethesda, Md.: Alban Institute, 1998). See also Gary L. McIntosh, One Size Doesn’t Fit All: Bringing Out the Best in Any Size Church (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Revell, 1999).

2. Michael and Deborah Jinkins, “Surviving Frustration in the First Years of Ministry,”Congregations (January/February 1994): 6–9.

3. See A. Richard Bullock and Richard J. Bruesehoff, Clergy Renewal: The Alban Guide to Sabbatical Planning (Bethesda, Md.: Alban Institute, 2000).

-------

IDEAS THAT IMPACT: COMMON MINISTRY CHALLENGES

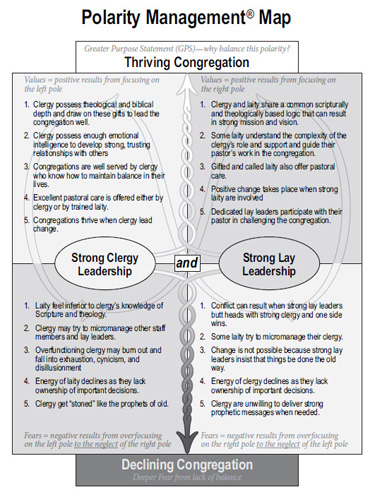

Failure to ThriveThriving congregations have found ways to empower their clergy and to empower their laity. It is important to do both. One way is to reproduce this polarity on a single sheet of paper and ask for an hour's discussion at the next board meeting. The question that needs to be asked at such a time is this: "Are we managing this polarity well or managing it poorly?"

Read more from Roy Oswald & Barry Johnson »

Failure to Thrive

John and Brigetta were pastors of neighboring congregations. Even though they represented different denominations, their congregations were quite similar. Both had approximately 110 members attending Sunday worship, and both congregations had been stuck at that number for the past eight years. John and Brigetta knew each other well, as they belonged to the same clergy support group, yet their leadership styles differed greatly.

Brigetta was a tough-thinking woman who made most of the decisions at Good Samaritan Church. She had a strong, driven, Type-A personality. Brigetta had a clear vision of where the congregation should be headed, and she worked tirelessly at getting laypeople to carry out her vision. Although she had great ideas, she continually encountered lackluster support for these proposals from the board and committee members. Some lay leaders had tried to revise some of her ideas to make them more relevant to congregational needs, but she insisted on their doing things her way. Brigetta repeatedly rebuffed their attempts to gain some ownership of her plans by incorporating some of their own, and in the end, they acquiesced to her. Over time, members who had leadership capacities simply stopped serving on congregational boards and committees. Brigetta had not noticed that lay leaders lacked enthusiasm because they felt they were treated as lackeys whose purpose was to carry out her vision. She, on the other hand, complained to her colleagues that she wished she had just a few capable lay leaders who wanted to do something to make the congregation thrive.

John was laid-back and easygoing. He also had a natural proclivity to pursue peace at all costs. Early in his tenure at St. John’s, he had tried exercising leadership but had found himself quickly overruled by strong-willed lay leaders who disagreed with the changes he wanted to make. After several attempts with the same results, he decided to offer the congregation excellent pastoral care and leave the leadership of the congregation in the hands of the strong lay leaders. He saw himself as carrying out the directions his lay leaders set for him, and he seemed willing to pay this price to keep the peace. Besides, these lay leaders were an intimidating bunch. They were tough, successful executives in their corporate settings, and in their opinion John knew little about either leadership or management. Sometimes he knew that what they were proposing would not work, because he was in touch with a much broader segment of the congregation. But he would bite his tongue and go along with their proposals, though his heart was not in them, and he gave only token support to implementing their ideas.

The Polarity to Be Managed

Here were two congregations going nowhere. In each case, there was no partnership between clergy and lay leaders. The congregations were stuck on alternate poles of this polarity, and both were experiencing more and more of the downside of their respective poles.

A polarity is a pair of truths that are interdependent. Neither truth stands alone. They complement each other. Congregations often find themselves in power struggles over the two poles of a polarity. Both sides believe strongly that they are right. People on each side assume that if they are right, their opponents must be wrong—classic “either/or” thinking. Either we are right or they are right—and we know we are right! When people argue about the two truths, both sides will be right, and they will need each other to experience the whole truth.

Let’s take a look at each quadrant in the “Strong Clergy Leadership and Strong Lay Leadership” polarity in detail:

The Upside of Strong Clergy Leadership

The Upside of Strong Clergy Leadership Clergy possess theological and biblical depth and draw on those gifts to lead the congregation well

Clergy possess enough emotional intelligence to develop strong, trusting relationships with others

Congregations are well served by clergy who know how to maintain balance in their lives

Excellent pastoral care is offered

Congregations thrive when clergy lead congregational change

Strong prophetic messages are delivered when necessary

The Upside of Strong Lay Leadership

- Clergy and laity share a common scripturally and theologically based logic that can result in strong mission and vision

- Some laity understand the complexity of the clergy’s role and support and guide their pastor’s work in the congregation

- Gifted and called laity also offer pastoral care

- Positive change takes place in a congregation when strong lay leaders are involved

- Dedicated lay leaders participate with their pastor in challenging the congregation

- Some laity may feel inferior to clergy in their knowledge of scripture, theology, and congregational life

- Clergy may try to micromanage other staff members and lay leaders

- Overfunctioning clergy may burn out and fall into exhaustion, cynicism, and disillusionment

- Lay leaders’ energy declines because they lack ownership of important decisions

- Clergy are, so to speak, stoned to death like the prophets of old

- Conflict can result when strong lay leaders butt heads with strong clergy, and one side wins

- Some laity try to micromanage their clergy

- Change is not possible because strong lay leaders insist that things be done the old way

- The energy of clergy declines as they lack ownership of important decisions

- Clergy are unwilling to deliver strong, prophetic messages

single sheet of paper and ask for an hour’s discussion at the next board meeting. The question that needs to be asked at such a time is this: “Are we managing this polarity well or managing it poorly?” If there is consensus that the congregation is managing it poorly, the board can ask for suggestions of action steps that might bring the two poles into better balance. If the suggestions are not particularly robust, a task force can be appointed to study the polarity and bring recommendations. Managing this polarity is worth that expenditure of energy.

____________________________________________

Adapted from Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities by Roy M. Oswald and Barry Johnson, copyright © 2010 by the Alban Institute. All rights reserved.

____________________________________________

FEATURED RESOURCES

Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities

Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities by Roy M. Oswald and Barry Johnson

A polarity is a pair of truths that need each other over time. When an argument is about two poles of a polarity, both sides are right and need each other to experience the whole truth. This phenomenon has been recognized and written about for centuries in philosophy and religion, and the research is clear: leaders and organizations that manage polarities well outperform those who don’t.

Leadership in Congregations

Leadership in Congregations Edited by Richard Bass

This book gathers the collected wisdom of more than ten years of Alban research and reflection on what it means to be a leader in a congregation, how our perceptions of leadership are changing, and exciting new directions for leadership in the future. With pieces by diverse church leaders, this volume gathers in one place a variety of essays that approach the leadership task and challenge with insight, depth, humor, and imagination.

Choosing Partnership, Sharing Ministry: A Vision for New Spiritual Community

Choosing Partnership, Sharing Ministry: A Vision for New Spiritual Community by Marcia Barnes Bailey

Partnership invites us on a journey that can transform us as leaders, as human beings, and as the church. Bailey invites pastors and congregations to a new understanding of ministry, leadership, and the church that challenges hierarchy by fully sharing responsibilities, risks, and rewards in mutual ministry. Partnership unleashes the Spirit to create a new vision and reality among us, moving us one step closer to living into God’s reign.

The Spirit-Led Leader: Nine Leadership Practices and Soul Principles

The Spirit-Led Leader: Nine Leadership Practices and Soul Principles by Timothy C. Geoffrion

Designed for pastors, executives, administrators, managers, coordinators, and all who see themselves as leaders and who want to fulfill their God-given purpose, The Spirit-Led Leader addresses the critical fusion of spiritual life and leadership for those who not only want to see results but also desire to care just as deeply about who they are and how they lead as they do about what they produce and accomplish. Geoffrion creates a new vision for spiritual leadership as partly an art, partly a result of careful planning, and always a working of the grace of God.

-------

Beating the Odds: Successfully Following a Long-Term Pastor

Every pastoral transition includes three players -- the preceding pastor, the congregation, and the new pastor. The most successful transitions occur when all three are fully committed to making the change work. The most disastrous transitions occur when none of the three play their parts well. The majority, of course, fall somewhere in between these extremes.

Read more from Rick Danielson »

Beating the Odds: Successfully Following a Long-Term Pastor

On a cold, winter Sunday morning, I entered my church study following worship and was startled to hear the door slam shut behind me. The woman facing me as I turned was an influential church leader. Her face burned as she thrust an angry index finger in my direction. With barely controlled words, she vented fury over the morning worship service. Beginning with unhappiness over a new song, she broadened her tirade to include a list of recent changes that had “ruined the church.” Before spinning on her heels to exit, she delivered the immortal words: “My husband grew up in this church, and I have been here for twenty-five years. We were here long before you came, and we will be here after you’re gone!”

Sinking into my chair, I shook my head and reviewed the events of the prior seven months. At age twenty-nine, I had been appointed to a mid-sized church with enormous potential for growth. The prospects had excited me and I had thrown myself into the new work with unbridled enthusiasm. The Staff Parish Relations Committee’s expressed desire for church growth had become my personal mandate. The results had been gratifying; within six months the church had left its twenty-year plateau to rise a full 50 percent in average worship attendance. New ministries and new groups had been started, and new members were sharing their gifts freely. I was flying high.

My feet touched the ground abruptly when I realized that not everyone was rejoicing. Longtime members complained that they did not know everyone anymore. New people put a strain on inadequate facilities. Generational issues erupted into open conflict. People questioned my motives publicly, accusing me of trying to build my own kingdom. Finally, an elderly man made explicit what I did not see for myself: most members were resolute in their desire to be a “small country church in the suburbs.” In retrospect, I realize that the waves of opposition I felt from some members had come as an immediate response to the first months of growth.

I wish this story had a happier ending. My tenure was only two years. I found a less stressful place to minister and watched from a distance as much of the growth that had occurred at my previous parish evaporated. It was easy to blame the unmotivated, unimpassioned people of the church for my departure, but as time passed I began to examine my own role. I had ignored the dynamics of following a well-loved, long-term pastor. I had discounted the impact of being the church’s first baby-boomer pastor. I had made a serious error in assuming that the Staff Parish Relations Committee spoke for the whole church, and I had neglected to know and love the people before setting off with my own agenda.

From a new position of humility, I began to ask questions. Would I have stayed longer if I had understood the unique dynamics of following a long-term pastor? Could I have built stronger relationships with members in order to create a base of support? I came to recognize that I had seriously underestimated the impact of following a strong pastor who had led the church for twelve years. My personality, age, leadership style, and ministry priorities differed significantly from his, but I had never considered how they would affect my ability to minister in that congregation. Unfortunately, insight came when it was too late to apply it to my own situation.

When Success Comes Unexpectedly

In the years that followed, I watched other pastoral transitions with great interest. Some matches of pastor and people were blissful from the start; others were unqualified disasters. And often the common wisdom regarding pastoral succession proved false, as was true in the case of the “Bishop of Danville.”

We used to speculate and laugh about the prospects at pastors’ meetings: who could ever replace Cal Sheasley when he finally retired? For twenty-five years the so-called Bishop of Dansville had reigned in southern Livingston County in New York. He reluctantly took the two-point charge of pastoring the Dansville and Sparta Center United Methodist Churches with the promise of something better if he could get the churches out of the red. By the time that happened, he realized he had found a home and had no intention of leaving. The churches responded to his leadership by growing in strength and number. He became pastor, in a sense, to all the people of Dansville, an inseparable part of the fabric holding the community together.

But even lengthy pastorates do not last forever. Sheasley’s ongoing heart problems cinched his decision to retire. But who could possibly replace a man who had grown so large in the hearts and minds of the people of Dansville?

Jamie Stevens received the call while attending a conference out of state. The bishop’s cabinet wanted him to consider taking the Dansville charge. Stevens’s heart sank. His current ministry had been fruitful, and his roots had grown deep. But in the days that followed he could not shake the certainty that this was God’s appointment for him. He agreed to go.

In the months following Sheasley’s announcement that he would be retiring, he prepared the churches for his leaving. He explained that he would no longer be baptizing their children or otherwise functioning in a pastoral role. One year before his retirement, he had led the church to replace the aging parsonage with a beautiful new home. He and his wife Norma paid the price of moving twice in twelve months in order to provide an adequate parsonage for the new pastor. “Cal determined before he left that he would do whatever it took to be an asset to me,” says Stevens. “He had a clear-cut plan in place that he made absolutely clear to both churches before he left and long before I was introduced to the people.”

Although Sheasley stepped aside from the role of pastor, he did not leave the community. He worshiped at first with another congregation, but returned a few months later at Stevens’s invitation. Norma Sheasley offered her resignation as church organist, but Stevens persuaded her to stay. The Sheasleys remain an active and beloved part of the Dansville congregation and Cal Sheasley occasionally takes on leadership roles at Stevens’s invitation. Sheasley refers to Stevens as his pastor and is determined to fully support him in that role.

Some said the appointment would not work, that only a short-term interim pastor could follow Sheasley’s twenty-five-year legacy. They have been proven wrong. Stevens is quick to give Sheasley the credit, remarking that he loved the churches more than he loved himself. As a result, says Stevens, “They were allowed to love me without feeling they were betraying Cal.” Considering his own role, Stevens states, “I really came in without a lot of preconceived notions and definitely without any concerns. So I was free to be what I needed to be—who I am.” The churches, in turn, welcomed their new pastor with open arms as a testimony to the effective and faithful ministry of Cal Sheasley.

Conventional wisdom says a former pastor should distance himself or herself from a congregation recently served as much as possible. It also claims that those unfortunates who follow a long-term pastor are destined to become unintentional interims. What else does such “wisdom” teach us? Consider the issue of change. Don’t make changes during the first year, right? Unless you listen to other experts, who advocate early changes to establish leadership. Deciding who is correct on such matters can be maddening until you realize that there are no simple, hard-and-fast, works-every-time rules for pastoral transitions. Imagining that there are only distracts from a more important issue: as in all of life, who you are in a time of transition matters far more than what you do.

When Gifted People Fail

Ever wonder why highly respected people with a proven track record can bomb so spectacularly when they move to a new position? Is it because they got in over their heads? Because they were lacking specific, needed leadership tools? Perhaps so, but it is just as likely—or more so—that they neglected underlying matters related to character. Consider the furor that erupted at another United Methodist church in New York when a new pastor took the reigns.

Years ago, when Pastor A had his introductory meeting with a group of leaders from the church, he asked what the people in the congregation were proud of. He thought they might comment on their Sunday school program or the church’s mission involvement. Their answer surprised him. “This room,” they replied, explaining that a recent remodeling project had transformed a drafty and unattractive space into a beautiful memorial chapel and lounge. For the next fourteen years, Pastor A led the church into new areas of ministry and greater levels of spiritual vitality. But he never forgot to affirm their past and always tried to honor the things they valued—including the memorial chapel.

When Pastor A moved on to a denominational position, Pastor B was called to serve the church. His prior ministry experience had been fruitful and he was ready to see great things happen in his new setting. Soon after arriving, he met with the trustees in the memorial chapel. “This room is the perfect location for the church nursery,” he remarked. The trustees had reservations. The memorial committee was upset, and when the women’s fellowship heard the plan a full-scale rebellion broke out. Pastor B responded forcefully by reminding them that he was the resident expert on church growth and that they would be wise to follow his suggestions. In the end he won the battle and the chapel became a nursery, but by then he had moved on to another church to escape the conflict that had ensued at the church as the result of his insistence on this particular change.

The Keys to Success

As the result of my own early experience as the successor to a long-term pastor and my observations of other pastorates that came on the heels of a long-tenured predecessor, my interest in what it took to successfully follow a long-term pastor deepened and I decided to examine the subject even more closely. I interviewed pastors and studied churches where a long-term pastorate had ended and a new pastor had taken up the reigns either successfully or unsuccessfully. I came to understand that congregations, outgoing pastors, and their incoming successors form an interrelated system. Each has a specific role in the transition.

Regarding former pastors, I discovered that the choices outgoing pastors made in relating to the congregation and supporting the new pastor were much more important than whether or not the former pastor remained in the church and community. It was also obvious that a healthy process of grieving and letting go of the predecessor’s role as pastor was critical for the congregation to be able to welcome and follow the new pastor.

While each player in the transition is necessary, it became increasingly obvious that the incoming pastor has the power to make or break the transition in most situations. The pastors themselves confirmed this truth as they told their stories. Five themes became clear through my research, which included interviews with twenty clergy.

1. Ego strength undergirds effective leadership. One pastor expected resistance to the significant changes he initiated in the first months at his new parish. When chaos reigned after four weeks, this confident pastor reminded himself that the changes were necessary. When the personal attacks came and he wasn’t sure when—or if—the battles would end, he calmly persisted with his plan. Within several months the church turned a corner. The pastor’s strong but not cocky leadership had won the respect of the congregation and led them to a much more fruitful ministry.

Another pastor was enormously bothered by the presence of his predecessor in the congregation. Week after week his resentment deepened and references by parishioners to the former pastor chipped away at his confidence. He and his wife sank into depression, asking, “What have we done wrong? Why won’t they accept us?” When asked about his experience of several years, the pastor answered every question by referring to the impossible situation his predecessor had created.

Ego strength might be defined as having a strong sense of self that allows one to act with confidence and not be unduly influenced by others or by situations beyond one’s control. More often than not, pastors expressing that kind of ego strength succeed in their new assignments.

2. There is no substitute for love. One congregation I studied sent people to spy on the young woman they had recently appointed to be their next pastor. She was preaching that Sunday on her favorite topic: love. They returned to spread the word, “She’s got the right message!” Beaten down by a self-proclaimed “prophet,” the people warmed to the new pastor, who not only preached love but showed through her actions how much she cared for them.

Another pastor spewed contempt throughout an interview: The people of the congregation were deceitful, resistant, ungrateful, and lazy. His predecessor had given him a bad deal. The sneer on his face spoke volumes. There was no love for the people God had sent him to serve. The observations he described were formed on arrival, and the bitterness he felt toward his predecessor was deep. Little improvement in the situation appears likely unless there is a change of heart in the pastor himself.

People respond to love. One pastor was told by a search committee at their first meeting, “We just want someone who likes people.” Perhaps saying that all that matters is love is overly simplistic, but without love for the congregation no pastor can succeed.

3. Self-awareness makes for effective pastoring. One pastor made numerous references to her own style, personality, and ministry priorities. She was candid about some of her limitations and shared mixed feelings about having her predecessor present in the church. From an outsider’s standpoint, the match of pastor and congregation after a particularly long prior pastorate did not look promising. But in fact the transition has been quite successful, most likely due to the new pastor’s conscious awareness of how her own attitudes and feelings might be influencing her.

Another pastor believed he had all kinds of insights into the dysfunction of his congregation. He said the people were unwilling to let him lead despite his excellent efforts. The more he talked, however, the more questions I had about his self-awareness since he could not see the rather obvious role he played in the breakdown of communication in the church.

Without self-awareness, pastors continue to repeat unhealthy patterns and never see the relationship between their actions and the response of the congregation. Understanding one’s assets and liabilities is especially critical when navigating the tricky waters following a long pastorate.

4. Understanding congregational dynamics is half the battle. One pastor could not comprehend why his congregation did not respect his authority. Yet he obviously did not understand how the congregation functioned, what they valued, and what they needed in a leader. He listed the problems he saw in the church but had no clue how to address them. Sadly, the conversation was a sort of “exit interview” among the boxes packed for his new assignment.

Another pastor I interviewed spoke of the dynamics of the congregation she served in terms of its systems. She understood the impact of the church’s history and the need to address issues previously unresolved. In four years the congregation made significant needed changes as the pastor wisely utilized the existing systems of the church to guide the people toward a better future.

Pastors need the capacity to see

the big picture of the church if they are to succeed in any new pastorate. Understanding the dynamics of a specific congregation is especially crucial when following a long-term pastor, since those dynamics are deeply rooted.

5. Persistence can turn the tide. Study participants who, in effect, succeeded themselves after a rocky start illustrate the importance of persistence. One such pastor was sure he was destined to be an “unintentional interim” but never felt a particular call to leave. To his surprise, the dynamics shifted after several years and he began to experience a powerful and fruitful ministry. He would have missed out on the blessing of the years that followed his rough start if he had left too soon. Unfortunately, some pastors appear to burn bridges early in their pastorates, making eventual bonding with the congregation difficult or impossible.

The Power of Three

Every pastoral transition includes three players—the preceding pastor, the congregation, and the new pastor. The most successful transitions occur when all three are fully committed to making the change work. The most disastrous transitions occur when none of the three play their parts well. The majority, of course, fall somewhere in between these extremes. Perhaps the new pastor’s predecessor is moderately supportive or neutral in his or her influence, the congregation adopts a wait-and-see attitude, or the new pastor struggles for months or years with his or her own feelings about the change. When enough factors eventually tip the balance for good, a positive relationship forms. Conversely, situations with potential for success eventually disintegrate without the necessary ongoing efforts to succeed.

No absolute formula for success or failure in pastoral transitions can be stated. It appears, however, that the predecessor can have tremendous influence for good. It also seems clear that the lack of that can be compensated for if the congregation and the new pastor play their parts well. The congregation seems to be the most flexible of the three, responding to the influence of the predecessor and/or successor, but it is unlikely that a successful transition can occur if the congregation is not at least moderately supportive the new pastor at the start.

Ultimately, the most critical player in every transition is the new pastor. If she or he deploys wisdom, skill, character, and love, the likelihood is great that the transition will eventually succeed despite obstacles placed by the predecessor or the congregation. Far better, though, for all three to cooperate for the sake of God’s work.

________________________

Questions for Reflection

- Does your congregation have a plan for affirming the ministry of your departing pastor?

- How will you welcome a new pastor into the life of your church?

- Do you know the basic “character qualities” for a new pastor as you face a time of transition?

- If your former pastor had a tenure of ten years or more, what impact do you anticipate that having on the transition?

LAST CHANCE: DENOMINATIONAL LEADERSHIP APPLICATION DEADLINE SEPTEMBER 19

Denominational Leadership

A Program of Leadership Education at Duke Divinity School

October 31 - November 3, 2016 | Chapel Hill, NC

It seems like only yesterday that you were the pastor of a congregation, and now you are offering leadership to your denomination at the regional or national level. Not only are the scope and scale of your responsibilities different, so too are your available resources and the ways you can lead effectively. This four-day educational event is designed so you can consider your practice of leadership and be equipped with the tools and strategies you need to navigate the complexities and changing landscape of denominational and institutional life today.

People of all denominations who are transitioning into executive-level positions within denominational governing bodies or who have been in their role fewer than three years are welcome to apply for this selective program.

Read more and apply »

PROGRAMS

DENOMINATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Overview

Taking part in Denominational Leadership inspired American Baptist official Larron Jackson that Christian leaders need to move beyond church walls to truly fulfill their mission.

The program challenged him “to see ministry not simply along denominational lines, but to hear Christ’s voice afresh in this age in which we are called to minister,” he said. “I got more than I had hoped I would get from it. A whole lot more.”

READ HIS STORY »

FEATURES

‘I CAME AWAY WITH A NEW ZEAL’

Larron JacksonMinistry and missions coach, Denver cluster, American Baptist Churches USA

Denominational Leadership participant

For the Rev. Dr. Larron Jackson, taking part in Denominational Leadership crystallized a question he already had been considering: How can we be faithful to our traditions and yet break free to witness for Christ in this time?

“We do wonderful in the sanctuary. We have our traditions, our music, the sermons — everything comfortable. But how do we go out and sing the Lord’s song in a different land? How do we go out and talk to people?” he said.

Jackson is a former NFL offensive guard who detailed his rough-and-tumble path to the pulpit in his autobiography, “The Ghetto, the Gridiron and the Gospel.” He heeded a call to ministry in 1978, at the end of his football career, and earned an M.Div. from the Candler School of Theology and a doctorate from Union Theological Seminary.

An official in the American Baptist Churches USA, Jackson said participating in the four-day-long program in 2013 “has really created an unrest in my spirit, but it’s a good unrest.”

Sessions with faculty members Dave Odom and Marlon Hall were particularly inspiring, he said, driving home the idea that ministry has to change to survive — and to fulfill its mission.

“I think both of them challenged us to see ministry not simply along denominational lines, but to hear Christ’s voice afresh in this age in which we are called to minister,” he said.

“I came away with a new zeal — I’ve been telling everyone about the leadership experience we had together.”

Jackson said there were a number of rich aspects in the Denominational Leadership program: the educational experience, thinking about denominations in new ways and engaging with other leaders from different traditions.

“I got more than I had hoped I would get from it,” he said. “A whole lot more.”

-------

It seems like only yesterday that you were the pastor of a congregation, and now you are offering leadership to your denomination at the regional or national level. Not only are the scope and scale of your responsibilities different, so too are your available resources and the ways you can lead effectively. This four-day educational event is designed so you can consider your practice of leadership and be equipped with the tools and strategies you need to navigate the complexities and changing landscape of denominational and institutional life today.

People of all denominations who are transitioning into executive-level positions within denominational governing bodies or who have been in their role fewer than three years are welcome to apply for this selective program.

This event will offer participants:

a variety of learning experiences designed to develop their individual leadership capacity;

the opportunity to learn about their leadership by receiving 360-degree feedback;

ways of understanding change processes and transition times;

strategies for practicing innovation at the regional or national level;

tools for responding to challenges that are particular to the work of a denominational executive, including managing personnel processes, having “critical conversations” and offering difficult feedback; and

times to network with colleagues in similar positions.

The faculty for this event include those with extensive experience working with denominations and other organizations. The event will feature special guest speakers such as Marlon Hall, pastor and Christian leader of the Awakenings Movement in Houston.

Please explore the other menu items to learn more about this program.

What We Offer

- ONLINE OFFERINGS

- Faith & Leadership

- PROGRAMS

- Executive Certificate in Religious Fundraising

- Sourcing Innovation

- Foundations of Christian Leadership

Questions We Answer

We know that you grapple with many difficult questions as a Christian leader. We want to help. Complex concerns about ministry can’t be fully addressed here, of course, but we provide a starting point for engaging the deep issues.

CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP

What is distinctly Christian about being a Christian leader?How do my Christian convictions shape the way that I lead? It is the end — the goal, the purpose, the telos — that shapes Christian leadership and makes it most distinctively Christian. Our end is to cultivate thriving communities that bear witness to the inbreaking reign of God that Jesus announces and embodies in all that we do and are.

LEARN MORE »

INSTITUTIONS

By thinking in a way that holds the past and future in tension, not in opposition. L. Gregory Jones coined the phrase “traditioned innovation” to describe a biblical way of leading that integrates the transformative work of Christ into our ongoing identity as the people of God rooted in biblical Israel’s calling.

LEARN MORE »

MANAGEMENT

The immediacy of a crisis makes it tempting to roll up our sleeves and work harder. But some problems are “wicked” — without clear starting and ending points, crossing social and conceptual boundaries — and require unconventional strategies.

LEARN MORE »

MORE QUESTIONS WE ANSWER »

FROM THE ALBAN LIBRARY

Ministers often find themselves caught in the day-to-day pressures of leading a congregation and yearn to experience the unfolding of their professional lives from a larger perspective. Four Seasons of Ministry serves as a guide for what you will find on your ministerial journey and gives meaning to the routine and repetitive tasks of ministry. Authors Bruce G. and Katherine Gould Epperly, each of whom has over 25 years of experience in various pastoral roles, invite clergy to see their ministries in the present as part of a life-long adventure in companionship with God, their loved ones, and their congregations. There is a time and a season to every ministry. Healthy and vital pastors look for the signs of the times and the gifts of each swiftly passing season, but they also take responsibility for engaging the creative opportunities of each season of ministry. Those who listen well to the gentle rhythm of God moving through their lives and the responsibilities and challenges that attend the passing of the years, vocationally as well as chronologically, will be amazed at the beauty and truth that shapes and characterizes the development of their ministries.

Ministers often find themselves caught in the day-to-day pressures of leading a congregation and yearn to experience the unfolding of their professional lives from a larger perspective. Four Seasons of Ministry serves as a guide for what you will find on your ministerial journey and gives meaning to the routine and repetitive tasks of ministry. Authors Bruce G. and Katherine Gould Epperly, each of whom has over 25 years of experience in various pastoral roles, invite clergy to see their ministries in the present as part of a life-long adventure in companionship with God, their loved ones, and their congregations. There is a time and a season to every ministry. Healthy and vital pastors look for the signs of the times and the gifts of each swiftly passing season, but they also take responsibility for engaging the creative opportunities of each season of ministry. Those who listen well to the gentle rhythm of God moving through their lives and the responsibilities and challenges that attend the passing of the years, vocationally as well as chronologically, will be amazed at the beauty and truth that shapes and characterizes the development of their ministries. Learn more and order the book »

-------

Follow us on social media:

VISIT OUR WEBSITE

Alban at Duke Divinity School

VISIT OUR WEBSITE

Alban at Duke Divinity School

1121 West Chapel Hill Street, Suite 101

Durham, North Carolina 27701, United States

-------

-------

No comments:

Post a Comment