PRACTICAL WISDOM FOR LEADING CONGREGATIONS

"Staff Designs in the 21st Century" by John Wimberly

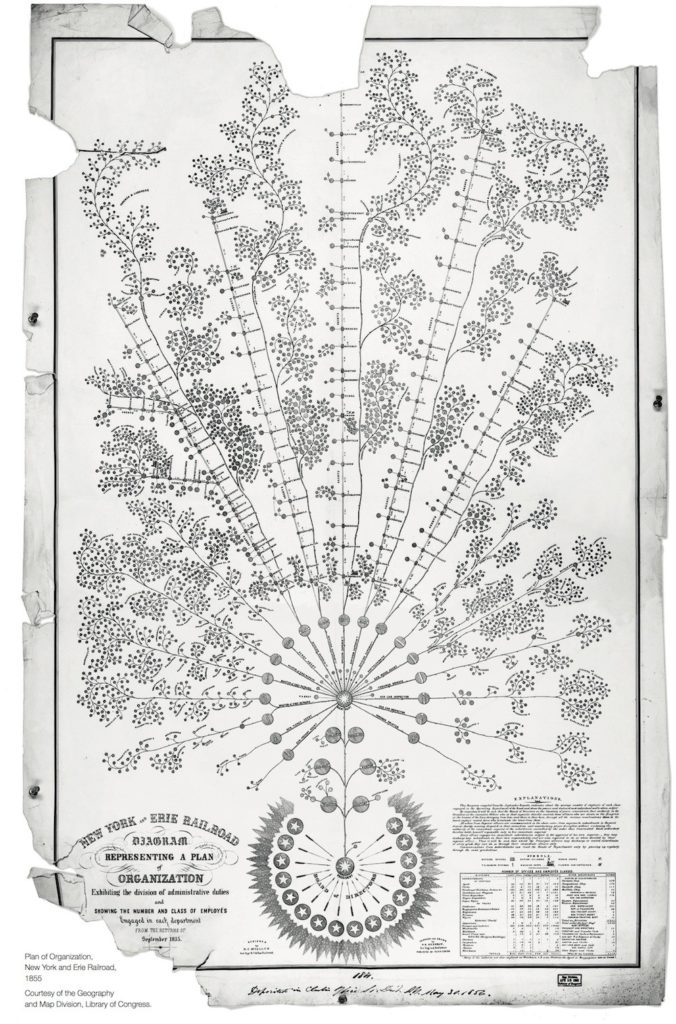

1855 Org Chart: Library of Congress

The positions that dominated church staffs in the 20th century don’t necessarily work in the 21st century. Instead of reflexively hiring an associate pastor to replace an associate who has departed, many congregations now hire people with specific skills—in communication, marketing, fundraising, and other needed specialties. Congregations and judicatories also are evaluating whether ministry work can sometimes be done better by part-time than full-time people.As a result, an increasing part of my consulting work is to help congregations and judicatories rethink their staff designs. The ministry needs of congregations today are, in many instances, significantly different from the past. What are some of the issues congregations and judicatories consider regarding how best to use their personnel budgets?

- Communications: The church secretary was once responsible for collecting articles for a monthly newsletter, assembling them into an attractive form, printing and stuffing the newsletter into envelopes, and then mailing them. Today, fewer and fewer congregations rely on hard copy dissemination of information as a primary communication tool. As a result, they need a staff person skilled at the ways people communicate today: eblasts, websites, text messages, Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. Finding a traditional secretary who has the communication skills needed today can be a challenge. Increasingly, congregations hire a person whose full- or part-time job is to handle electronic communications.

- Religious Education: Many congregations no longer have large, traditional religious education programs. Sunday morning soccer, among many other things, has sabotaged Sunday school attendance across the country. Consequently, congregations question the need for a full-time religious education person (ordained or not). Increasingly, they opt for part-time religious educators who can work at times other than Sunday mornings when programs are more likely to attract critical mass.

- Stewardship: Younger generations make contributions to congregations in ways that are very different from those who sat in the pews ten years ago. They are inclined to text a contribution, scan a QR symbol in the bulletin, or respond to an eblast with a solicitation for a particular church need. Congregations are hiring people to help them manage the transition from a pledge-based revenue stream to whatever is coming next.

- Finances: The use of financial management programs such as QuickBooks has changed the amount of time needed for handling the money as well as the skill set required to do the job. What are the roles of the Treasurer and bookkeeper in a system where the bulk of the work is done with software?

- Secretarial/Administrative Work: There is still a need for administrative work in a church, but the nature of that work has changed dramatically. Several decades ago, the church secretary put together the worship bulletin. Today it can be done by pastor(s) using templates created with word processing software. Secretaries used to type letters and other documents. Now pastors do that work themselves. Secretaries sometimes managed the pastor’s calendar. Today it can be done by the pastor using web-based software accessible on a mobile phone.

- Building Maintenance: Many congregations are using or considering cleaning services instead of having a staff member do the work. Some congregations find it is a cheaper option. Other congregations find the lack of personal relationships between a janitor/sexton and the congregation too important to lose.

Think Different

While there may be some financial advantages to hiring part-time staff, managing them can be challenging. Part-time staff typically have another major time commitment in their life (another job, parenting, education, etc.). As a result, they may not be available when congregations need them.

My advice to congregations is simple: Don’t automatically replace departing staff with another person doing exactly the same work. Use staff turnover as an opportunity to examine how those dollars might be better used in a different staff configuration. After a thorough evaluation of the options, a congregation may decide to keep the same job description. But it may find that a different staff alignment optimizes their personnel dollars. Spending time thinking strategically about staff design makes hiring easier and results in a more effective staff team.

About John Wimberly

John Wimberly is the author of the new Alban book Mobilizing Congregations: How Teams Can Motivate Members and Get Things Done. He consults with congregations on issues such as the creation and implementation of strategic plans, congregational growth and the empowering use of endowments. John served congregations for 38 years, 30 of them at Western Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC. His quest for continuing personal, spiritual and professional growth led John to complete a PhD in systematic theology and an Executive MBA program.

The Death of Denominations?

At last week's General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA), conversations often turned to the question: “Is the end near for our denomination?” Each year the number of affirmative answers seems to increase. I don’t agree. I don’t think mainline denominations are in danger of dying any time soon.

Continue reading from John Wimberly »

What is the “right” ministerial staff size for a congregation of a particular size? This is a difficult question in part because the answer depends on what a congregation expects of its clergy. Some clergy tasks, like preparing a sermon, do not necessarily require more time in a 500-person congregation than they require in a 100-person congregation. But other clergy tasks, like visiting people in the hospital or hearing confessions, take up more time as the number of people increases. If people expect a visit from a clergyperson every time a member is in the hospital, or if they expect a host of professionally organized youth activities, or, more broadly, if people expect that every member will be personally known in a meaningful sense by their minister, priest, or rabbi, then congregations will have to add ministerial staff about as fast as they add people. If it takes one full-time clergyperson to do this work properly in a 100-person congregation, it will take 5 to do it properly in a 500-person congregation.

What is the “right” ministerial staff size for a congregation of a particular size? This is a difficult question in part because the answer depends on what a congregation expects of its clergy. Some clergy tasks, like preparing a sermon, do not necessarily require more time in a 500-person congregation than they require in a 100-person congregation. But other clergy tasks, like visiting people in the hospital or hearing confessions, take up more time as the number of people increases. If people expect a visit from a clergyperson every time a member is in the hospital, or if they expect a host of professionally organized youth activities, or, more broadly, if people expect that every member will be personally known in a meaningful sense by their minister, priest, or rabbi, then congregations will have to add ministerial staff about as fast as they add people. If it takes one full-time clergyperson to do this work properly in a 100-person congregation, it will take 5 to do it properly in a 500-person congregation.

The National Congregations Study can’t tell us what the right number of ministerial staff might be, but it can tell us the average number of full-time ministerial staff in congregations of various sizes. This is what the above graph portrays for three broad families of congregations. Note that “full-time ministerial staff” here does not necessarily mean seminary-trained or ordained staff. It means full-time staff who, to give the wording of the survey question on which this graph is based, “would be considered ministerial or other religious staff, such as youth ministers, other pastors, pastoral counselors, directors of religious education, music ministers, and so on.” Respondents were told not to count secretaries, janitors, school teachers, or other full-time employees not primarily engaged in religious work. The analysis behind this graph also is limited to congregations having at least 1 full-time ministerial staff person; congregations with no full-time staff are excluded.

The most obvious feature of this graph is that white Protestant churches are, at every size, more heavily staffed than Catholic churches or Black Protestant churches. The median white Protestant church with as few as 200 regularly participating adults (which in general means significantly more than 200 members) has 2 full-time ministerial staff people. Catholic and Black Protestant churches don’t reach an average of 2 full-time ministerial staff until they are twice that size.

These differences do not by themselves imply that white Protestant churches are overstaffed, or that Catholic and Black Protestant churches are understaffed. The differences surely indicate a combination of traditional differences in clergy roles across these groups, differences among these groups in the expectations people have of their clergy, and differences in the resources available for paying staff. Whatever is behind these differences, though, the results clearly indicate that white Protestant congregations have more full-time ministerial staff per capita than either Catholic or Black Protestant congregations.

The other interesting, though less obvious, feature of this graph is that these lines, which represent the best fit to the data, bend downward, meaning that larger congregations, per capita, have somewhat fewer full-time ministerial staff than smaller congregations. For white Protestant churches, I mentioned above that a 200-person church has, on average, 2 full-time ministerial staff. The average number of full-time ministerial staff does not double to 4 until we reach congregations with 500 regularly participating adults, and it doesn’t double again to 8 until we reach 1,150 people. A congregation with 1,000 regularly participating adults is 5 times larger than a 200-adult congregation, but, roughly speaking, it has not quite 4 times as many full-time ministerial staff. The numbers are smaller, but the pattern is similar, for Catholics and for Black Protestants. Larger congregations have fewer per capita full-time ministerial staff than smaller congregations.

Does this mean that, whatever the differences across religious traditions in what people expect of clergy, larger congregations within at least these three broad religious groups are in general more efficient than smaller congregations? It is difficult to say. The number of full-time staff is not the only factor that would be relevant in an overall assessment of congregational efficiency. And if having fewer per capita ministerial staff means that people are served less well in larger than in smaller congregations, then a lower staff-to-member ratio represents no gain in efficiency. To be more efficient means that we do more with less; doing less with less is not increasing efficiency. Knowing whether or not larger congregations are more efficient than smaller congregations requires knowing, among other things, whether people in them are served at least as well as people in smaller congregations even though the ministerial staff is proportionally smaller.

Read more from Mark Chaves »

The Death of Denominations?

At last week's General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA), conversations often turned to the question: “Is the end near for our denomination?” Each year the number of affirmative answers seems to increase. I don’t agree. I don’t think mainline denominations are in danger of dying any time soon.

Continue reading from John Wimberly »

IDEAS THAT IMPACT: STAFFING

Faith & Leadership

A learning resource for Christian leaders and their institutions from Leadership Education at Duke Divinity

In this archive column, sociologist Mark Chaves asks what data collected as part of the National Congregations Study might suggest about whether there is a "right" sized staff.

Mark Chaves: What's the "right" sized staff?

Can you hire fewer people per worshiper the bigger your congregation is?

The National Congregations Study can’t tell us what the right number of ministerial staff might be, but it can tell us the average number of full-time ministerial staff in congregations of various sizes. This is what the above graph portrays for three broad families of congregations. Note that “full-time ministerial staff” here does not necessarily mean seminary-trained or ordained staff. It means full-time staff who, to give the wording of the survey question on which this graph is based, “would be considered ministerial or other religious staff, such as youth ministers, other pastors, pastoral counselors, directors of religious education, music ministers, and so on.” Respondents were told not to count secretaries, janitors, school teachers, or other full-time employees not primarily engaged in religious work. The analysis behind this graph also is limited to congregations having at least 1 full-time ministerial staff person; congregations with no full-time staff are excluded.

The most obvious feature of this graph is that white Protestant churches are, at every size, more heavily staffed than Catholic churches or Black Protestant churches. The median white Protestant church with as few as 200 regularly participating adults (which in general means significantly more than 200 members) has 2 full-time ministerial staff people. Catholic and Black Protestant churches don’t reach an average of 2 full-time ministerial staff until they are twice that size.

These differences do not by themselves imply that white Protestant churches are overstaffed, or that Catholic and Black Protestant churches are understaffed. The differences surely indicate a combination of traditional differences in clergy roles across these groups, differences among these groups in the expectations people have of their clergy, and differences in the resources available for paying staff. Whatever is behind these differences, though, the results clearly indicate that white Protestant congregations have more full-time ministerial staff per capita than either Catholic or Black Protestant congregations.

The other interesting, though less obvious, feature of this graph is that these lines, which represent the best fit to the data, bend downward, meaning that larger congregations, per capita, have somewhat fewer full-time ministerial staff than smaller congregations. For white Protestant churches, I mentioned above that a 200-person church has, on average, 2 full-time ministerial staff. The average number of full-time ministerial staff does not double to 4 until we reach congregations with 500 regularly participating adults, and it doesn’t double again to 8 until we reach 1,150 people. A congregation with 1,000 regularly participating adults is 5 times larger than a 200-adult congregation, but, roughly speaking, it has not quite 4 times as many full-time ministerial staff. The numbers are smaller, but the pattern is similar, for Catholics and for Black Protestants. Larger congregations have fewer per capita full-time ministerial staff than smaller congregations.

Does this mean that, whatever the differences across religious traditions in what people expect of clergy, larger congregations within at least these three broad religious groups are in general more efficient than smaller congregations? It is difficult to say. The number of full-time staff is not the only factor that would be relevant in an overall assessment of congregational efficiency. And if having fewer per capita ministerial staff means that people are served less well in larger than in smaller congregations, then a lower staff-to-member ratio represents no gain in efficiency. To be more efficient means that we do more with less; doing less with less is not increasing efficiency. Knowing whether or not larger congregations are more efficient than smaller congregations requires knowing, among other things, whether people in them are served at least as well as people in smaller congregations even though the ministerial staff is proportionally smaller.

Read more from Mark Chaves »

Many congregations spend considerable time in the creation of job descriptions without asking the fundamental questions required to effectively design a staff role. Here, former Alban senior consultant Susan Beaumont applies wisdom from the Harvard Business School to this part of congregational life.

Many congregations spend considerable time in the creation of job descriptions without asking the fundamental questions required to effectively design a staff role. Robert Simmons of the Harvard Business School recommends addressing these four basic questions in the design of any staff position.1What resources will the staff member be able to control in order to accomplish assigned tasks? (Span of Control)

What measures will be used to evaluate the staff member’s performance? (Span of Accountability)

Who does the staff member need to interact with and influence to achieve goals? (Span of Influence)

How much support can the staff member expect when he or she reaches out to others for help? (Span of Support)

The Span of Control

The span of control defines the range of resources (people, assets, infrastructure) for which a staff member is given decision-making rights. Typically the span of control is established by assigning reporting relationships (who does this staff member report to and who reports to this staff member), assigning budget line items of responsibility, and setting spending limits. Different staff members should have different levels of authority when it comes to making decisions about allocating resources, but every member should have some defined level of freedom for decision making in their area of responsibility.

Entry level or inexperienced staff members will typically be assigned a narrow span of control, meaning that they have narrow decision-making rights. As a staff member grows in wisdom and experience, the congregation can widen the span of control as a form of leadership development. However, it is important that the span of control in each staff role relate logically to the span of control in corresponding staff positions. Your head of staff should always have a span of control that exceeds the span of control of every other staff member. A staff member should never have a span of control wider than the person to whom she reports.

A common question that emerges around the issue of span of control is this one. What is the appropriate number of people for any one person to supervise? There is no easy, uniform response to that question. Generally speaking, it is important to consider the number and ease of required contacts, the degree of specialization in the positions that report to a supervisor, and the ability to communicate with direct reports. Bear in mind that the number of potential interpersonal relationships between a supervisor and subordinate increases exponentially with each added direct report. This holds true because supervisors must contend with the direct relationships, with a group relationship, and with the cross relationships between each of the people that report to them. It is easier to supervise a group of people with very similar areas of specialization (e.g. youth small group leaders) than it is to supervise people with very different specializations. It is simpler to supervise people in close physical proximity than it is to supervise people who work at a distance. It is easier to supervise people who are very much alike in terms of temperament, background, and experience. The greater the diversity, the greater the distance, and the greater the variety of specializations the smaller the number of direct reports ought to be.

The Span of Accountability

The span of accountability refers to the measurable goals that a staff member is expected to achieve and the range of trade-offs available to affect those measures. A narrow span of accountability generally involves simplistic, easily definable measures: a line item in the budget, enrollment or attendance numbers, number of groups or classes offered, etc. In a narrow span there are few variables or trade-offs that can impact the outcome being measured. A wider span of accountability uses broader measures that incorporate many variables of congregational life. Examples include the general level of giving, overall worship attendance, and spiritual growth of the membership. The wider the span of accountability, the greater number of variables and the greater the number of trade-offs that must be managed.

Generally speaking, the span of control and the span of accountability ought to be established in tandem with one another. People should never be held accountable for things over which they have no control. However, a congregation that wants to encourage a creative and entrepreneurial spirit will try to set the span of accountability just a little bit wider than the span of control. This gap encourages risk taking and greater creativity. However, if the gap becomes too wide, employees become discouraged and frustrated at being held accountable for things outside their control.

The Span of Influence

The span of influence describes the width of the net that an individual needs to cast in gathering data, collecting new information, and attempting to influence the work of others. A staff member with a narrow span of influence does not need to pay much attention to people outside of his area of responsibility to do his job effectively. An individual with a wide span must interact with and extensively influence people in other areas of ministry. Generally speaking, in faith communities we are always seeking to enhance the community by building greater interconnectedness and wider spans of influence. However, at times it can be a waste of congregational resources, and even distracting to congregational mission, to encourage specialized entry level functions to influence all aspects of congregational life.

A congregation that is interested in increasing the span of influence among its staff members can take several actions. The job description can be rewritten to suggest a broader area of influence. Goals can be set that require broader interaction of staff members. Cross-functional teams can be established to tackle emerging projects and problems. The span of influence should be set a little wider than the span of control to encourage staff members to work across boundaries and solicit help from one another.

The Span of Support

The span of support refers to the amount of help an individual staff member can expect from people in other parts of the congregation. When the span of support is narrow, staff members are very highly focused on their own performance and accomplishment of goals. A wider span of support emphasizes shared responsibilities through purpose, mission, and strong group identification. A congregation cannot adjust a job’s span of support in isolation because it is largely determined by the staff’s sense of shared responsibilities, which in turn stems from a congregation’s culture and values. In most cases, all of a congregation’s staff will operate with a wide span of support, or none will. Various practices and policies of the congregation can help to create or destroy a shared sense of purpose and support among staff members. A clearly defined mission, fair and equitable pay practices, and clearly defined roles and responsibilities all contribute to wider spans of support within a congregation. Keeping the spans of control, accountability, influence, and support properly defined and aligned within a congregation can be challenging. However, thinking about your staff positions along these four dimensions will allow for better alignment of staff roles with congregational objectives. Over time each of the spans will likely shift in response to changes in congregational circumstances and strategies. Being intentional about revisiting and revising the four spans will enhance the effectiveness of your staff.

NOTE

1. Robert Simmons, “Designing High Performance Jobs,” Harvard Business Review(July-August 2005): 55-62.

Read more from Susan Beaumont »

After clarifying the differences between teams and committees, readers learn the important steps needed to set-up new teams. Leaders who simply create a team without attention to the formation process increase the likelihood of team failure. Using real-world examples and case studies, Wimberly addresses problems teams can expect to experience, as well as ways to resolve those issues. He highlights the surprising similarities between how teams and congregations function, both positively and negatively, providing keen insights from the business world and showing how they can be used to solve issues in congregations.

Here readers will find both the theory and practice of making a successful transition to a congregation doing its work through highly motivated, efficient teams.

Learn more and order the book »

The span of control defines the range of resources (people, assets, infrastructure) for which a staff member is given decision-making rights. Typically the span of control is established by assigning reporting relationships (who does this staff member report to and who reports to this staff member), assigning budget line items of responsibility, and setting spending limits. Different staff members should have different levels of authority when it comes to making decisions about allocating resources, but every member should have some defined level of freedom for decision making in their area of responsibility.

Entry level or inexperienced staff members will typically be assigned a narrow span of control, meaning that they have narrow decision-making rights. As a staff member grows in wisdom and experience, the congregation can widen the span of control as a form of leadership development. However, it is important that the span of control in each staff role relate logically to the span of control in corresponding staff positions. Your head of staff should always have a span of control that exceeds the span of control of every other staff member. A staff member should never have a span of control wider than the person to whom she reports.

A common question that emerges around the issue of span of control is this one. What is the appropriate number of people for any one person to supervise? There is no easy, uniform response to that question. Generally speaking, it is important to consider the number and ease of required contacts, the degree of specialization in the positions that report to a supervisor, and the ability to communicate with direct reports. Bear in mind that the number of potential interpersonal relationships between a supervisor and subordinate increases exponentially with each added direct report. This holds true because supervisors must contend with the direct relationships, with a group relationship, and with the cross relationships between each of the people that report to them. It is easier to supervise a group of people with very similar areas of specialization (e.g. youth small group leaders) than it is to supervise people with very different specializations. It is simpler to supervise people in close physical proximity than it is to supervise people who work at a distance. It is easier to supervise people who are very much alike in terms of temperament, background, and experience. The greater the diversity, the greater the distance, and the greater the variety of specializations the smaller the number of direct reports ought to be.

The Span of Accountability

The span of accountability refers to the measurable goals that a staff member is expected to achieve and the range of trade-offs available to affect those measures. A narrow span of accountability generally involves simplistic, easily definable measures: a line item in the budget, enrollment or attendance numbers, number of groups or classes offered, etc. In a narrow span there are few variables or trade-offs that can impact the outcome being measured. A wider span of accountability uses broader measures that incorporate many variables of congregational life. Examples include the general level of giving, overall worship attendance, and spiritual growth of the membership. The wider the span of accountability, the greater number of variables and the greater the number of trade-offs that must be managed.

Generally speaking, the span of control and the span of accountability ought to be established in tandem with one another. People should never be held accountable for things over which they have no control. However, a congregation that wants to encourage a creative and entrepreneurial spirit will try to set the span of accountability just a little bit wider than the span of control. This gap encourages risk taking and greater creativity. However, if the gap becomes too wide, employees become discouraged and frustrated at being held accountable for things outside their control.

The Span of Influence

The span of influence describes the width of the net that an individual needs to cast in gathering data, collecting new information, and attempting to influence the work of others. A staff member with a narrow span of influence does not need to pay much attention to people outside of his area of responsibility to do his job effectively. An individual with a wide span must interact with and extensively influence people in other areas of ministry. Generally speaking, in faith communities we are always seeking to enhance the community by building greater interconnectedness and wider spans of influence. However, at times it can be a waste of congregational resources, and even distracting to congregational mission, to encourage specialized entry level functions to influence all aspects of congregational life.

A congregation that is interested in increasing the span of influence among its staff members can take several actions. The job description can be rewritten to suggest a broader area of influence. Goals can be set that require broader interaction of staff members. Cross-functional teams can be established to tackle emerging projects and problems. The span of influence should be set a little wider than the span of control to encourage staff members to work across boundaries and solicit help from one another.

The Span of Support

The span of support refers to the amount of help an individual staff member can expect from people in other parts of the congregation. When the span of support is narrow, staff members are very highly focused on their own performance and accomplishment of goals. A wider span of support emphasizes shared responsibilities through purpose, mission, and strong group identification. A congregation cannot adjust a job’s span of support in isolation because it is largely determined by the staff’s sense of shared responsibilities, which in turn stems from a congregation’s culture and values. In most cases, all of a congregation’s staff will operate with a wide span of support, or none will. Various practices and policies of the congregation can help to create or destroy a shared sense of purpose and support among staff members. A clearly defined mission, fair and equitable pay practices, and clearly defined roles and responsibilities all contribute to wider spans of support within a congregation. Keeping the spans of control, accountability, influence, and support properly defined and aligned within a congregation can be challenging. However, thinking about your staff positions along these four dimensions will allow for better alignment of staff roles with congregational objectives. Over time each of the spans will likely shift in response to changes in congregational circumstances and strategies. Being intentional about revisiting and revising the four spans will enhance the effectiveness of your staff.

NOTE

1. Robert Simmons, “Designing High Performance Jobs,” Harvard Business Review(July-August 2005): 55-62.

Read more from Susan Beaumont »

FROM THE ALBAN LIBRARY

This is an in-depth look at the power teams bring to congregational work. Wimberly demonstrates that younger generations in particular are much happier working in a team, rather than a committee environment. Congregations using teams are able to mobilize members across generations for both short and long term tasks.After clarifying the differences between teams and committees, readers learn the important steps needed to set-up new teams. Leaders who simply create a team without attention to the formation process increase the likelihood of team failure. Using real-world examples and case studies, Wimberly addresses problems teams can expect to experience, as well as ways to resolve those issues. He highlights the surprising similarities between how teams and congregations function, both positively and negatively, providing keen insights from the business world and showing how they can be used to solve issues in congregations.

Here readers will find both the theory and practice of making a successful transition to a congregation doing its work through highly motivated, efficient teams.

Learn more and order the book »

Follow us on social media:

Copyright © 2018. All Rights Reserved.

Alban at Duke Divinity School

1121 West Chapel Hill Street,Suite 200

Durham, North Carolina 27701, United States

No comments:

Post a Comment