democracynow.org

Stories:

After Surviving 600 Assassination Attempts & Outlasting 11 U.S. Presidents, Fidel Castro Dies at 90

We host a roundtable discussion on the life and legacy of Cuban revolutionary leader and former President Fidel Castro, who died Friday at the age of 90. He survived 11 U.S. presidents and more than 600 assassination attempts, many orchestrated by the CIA. Castro died 60 years to the day after he, his brother Raúl, Che Guevara and 80 others set sail from Mexico in 1956 to begin what became the Cuban revolution to oust the U.S.-backed Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista. The revolution would inspire revolutionary efforts across the globe and lead Castro to become one of the archenemies of the United States. Our guests are journalist and activist Bill Fletcher, a founder of the Black Radical Congress; Peter Kornbluh, director of the Cuba Documentation Project and co-author of "Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana"; and Louis A. Pérez Jr., a professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the author of several books, including "Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution."

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: Today we spend the hour looking at the life and legacy of the Cuban revolutionary leader and former Cuban president, Fidel Castro. He died Friday at the age of 90. He survived 11 U.S. presidents and more than 600 assassination attempts, many orchestrated by the CIA. The Cuban government has declared nine days of national mourning. Castro had been in poor health since 2006 and formally ceded power to his younger brother, Raúl, in 2008. Fidel Castro died 60 years to the day after he, his brother Raúl, Che Guevara and 80 others set sail from Mexico in 1956 to begin what became the Cuban revolution to oust the U.S.-backed dictator, Fulgencio Batista. Batista fled Cuba in 1959, and the Castros have led Cuba ever since. The Cuban revolution would inspire revolutionary efforts across the globe and lead Castro to become one of the archenemies of the United States. This is Fidel Castro addressing his fellow Cubans in the 1980s.

PRESIDENT FIDEL CASTRO: [translated] Revolution is having a sense of the moment. It’s changed everything that must be changed. It’s complete equality and freedom. It’s to treat and be treated like a human being. It’s emancipating ourselves for ourselves and by our own strength. It’s challenging the dominant forces inside and outside the country. It’s defending our values at any price.

AMY GOODMAN: Fidel Castro embraced communism. He called himself a Marxist-Leninist. Washington repeatedly tried to remove him from power with the ill-fated invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961 and a decades-long economic embargo. Castro denounced the U.S. blockade of Cuba in the 1988 film The Uncompromising Revolution, directed by Saul Landau and Jack Willis.

PRESIDENT FIDEL CASTRO: [translated] For the first 10 years the revolution had to survive the blockade and create possibilities of development. In these years, basic progress occurred, like eradicating illiteracy, building an educational system, getting schools to remote areas, providing teachers. In those days, we even "improvised" teachers, because there weren’t enough teachers, plans to train doctors. Of our 6,000 doctors, 3,000 in 1959 were lured to the United States. We have had to face U.S. hostility, the blockade, great challenges. I think our responses were appropriate.

AMY GOODMAN: Across the developing world, Fidel Castro is viewed as a hero who stood up to the United States and assisted Marxist guerrillas and revolutionary governments around the world. In the 1970s, he sent Cuban troops to Angola to support the government over the initial objections of Russia. Cuba helped defeat South African insurgents in Angola and win Namibia’s independence from South Africa in 1990, adding pressure on the apartheid regime. After Nelson Mandela was freed from prison in 1990, he repeatedly thanked Fidel Castro. On Saturday, the leader of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola said Castro was like Mandela.

JULIÃO MATEUS PAULO: [translated] In the world, from time to time, there will be individuals like this who appear, be it in science or politics. These individuals are like our Mandela. And when they leave us, they leave us with a gap, emptiness and longing, because, for some, Fidel Castro was a dictator, but, for us, he was not. He was a revolutionary. Regardless of anything, he was also a charismatic figure. Even his Western enemies respected him. It’s difficult for people like that to exist in today’s world. These are rare people. They are geniuses.

AMY GOODMAN: Many Cubans who fled the regime consider Castro a tyrant who demanded absolute obedience from the Cuban people through censorship of the media and by imprisoning people he deemed antisocial, including dissidents, artists and members of the LGBT community. In July 2015, President Obama re-established formal diplomatic relations with Cuba. After Castro’s death was announced Friday, Obama released a statement saying, quote, "We know that this moment fills Cubans—in Cuba and in the United States—with powerful emotions, recalling the countless ways in which Fidel Castro altered the course of individual lives, families, and of the Cuban nation. History will record and judge the enormous impact of this singular figure on the people and the world around him," unquote. Donald Trump tweeted, "Fidel Castro is Dead!" exclamation point.

In Canada, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issued a statement that described Castro as "larger than life" and a "remarkable leader," quote, "a legendary revolutionary and orator" who "made significant improvements to the education and healthcare of his island nation," unquote. He also noted that his father, Pierre Trudeau, was proud to call Fidel Castro a friend.

All of this comes as several major U.S. airlines are beginning commercial flights to Cuba this week for the first time in 55 years. The first flight is landing today. Today, as we broadcast, that flight is leaving from New York to Cuba.

In April of this year, Castro gave what would be his farewell speech. Addressing the closing of a Communist Party Congress in Havana, he defended his record, saying, quote, "Soon I’ll be like all the others. The time will come for all of us, but the ideas of the Cuban communists will remain as proof on this planet that if they are worked at with fervor and dignity, they can produce the material and cultural goods that human beings need, and we need to fight without truce to obtain them," unquote.

When we come back, we host a roundtable discussion on Fidel Castro’s life and legacy. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Cuban musician Silvio Rodríguez. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we spend today looking at the life and legacy of the Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro, who died on Friday at the age of 90. We’re joined by three guests.

Bill Fletcher Jr. is a longtime labor, racial justice and international activist, editorial board member and columnist for BlackCommentator.com, founder of the Black Radical Congress, his recent piece headlined "Black America and the Passing of Fidel Castro."

Peter Kornbluh is also with us, director of the Cuba Documentation Project at the National Security Archive. He’s the co-author with William LeoGrande of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana.

And joining us via Democracy Now! video stream, Lou Pérez Jr., professor of history at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, author of several books, including Cuba in the American Imagination: Metaphor and the Imperial Ethos and Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution.

We welcome you all to Democracy Now! Peter Kornbluh, let’s begin with you. Your reaction to the death of Fidel Castro?

PETER KORNBLUH: Well, the world has lost one of the most famous leading and dynamic and dramatic revolutionaries who ever lived. He’s going to have a very controversial legacy, but it is indisputable that he took a small Caribbean island and transformed it into a major actor on the world stage, far beyond its geographic size. He stood up to the United States. He became the David versus Goliath, withstood all of the efforts to kill him, overthrow him. And that is what he will go down in history for, in many ways.

Cuba is in a very difficult situation today, with an extraordinary transition in terms of the Cuban leadership and in terms of the leadership in the United States. It’s not clear where the relationship between Washington and Havana is going to go under Donald Trump. And in that respect, the death of Fidel now is—comes at an extremely delicate moment. But, you know, the world is going to, I think, remember Fidel as somebody who really stood for independence and sovereignty and brought a great pride and nationalism to the Cuban people.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Bill Fletcher, your immediate response when you heard that Fidel Castro had died? I mean, he was no longer the actual president; he had handed over power in 2006 to his younger brother, Raúl, who’s actually 85, and then formally ceded that power in 2008, so it’s been about a decade.

BILL FLETCHER JR.: Much as—Amy, as Peter just said, we lost a very audacious leader, an outspoken champion of national liberation, national independence. And while there are, you know, in the mainstream media many, many criticisms that are being made of Fidel Castro—and there are certainly legitimate criticisms—what the U.S. media misses is why is it that most of the world mourns his passing. It’s not just the mourning of a historic figure, but a figure who actually shook up the planet.

AMY GOODMAN: In what way?

BILL FLETCHER JR.: He did things that were really—it’s just interesting, Amy. He took a—he took a country that had been turned into a whorehouse and gambling casino for the United States, and gave that country dignity. He turned a country that was poor—remains poor—into a major location for the production of medical personnel, who have gone around the world and made themselves available to countries that could never afford that kind of assistance. He—as Peter mentioned, he combated the apartheid regime in South Africa, but, in addition, provided all sorts of assistance to forces that were fighting Portuguese colonialism and white minority rule. He helped to construct the idea of Latin American independence, working very closely with the late President Chávez of Venezuela. And this is one of the reasons that he has a special place for much of black America, that he stood up to the United States. The United States did everything that they could possibly do to destroy him, to bring him down and to bring down his government, and it did not work.

AMY GOODMAN: Lou Pérez, talk about your interest in Fidel Castro and your response to this latest development, the death of Fidel Castro.

LOUIS PÉREZ JR.: Good morning. I think it’s important to contextualize Fidel Castro. What resonates in the world, at least as much as Fidel Castro, is the Cuban revolution. And the Cuban revolution itself is a historical process that comes out of 100 years of struggle. The Cuban revolution represents the culmination of Cuban history. And behind Fidel Castro, or perhaps even ahead of Fidel Castro, are a people, a people who have been struggling for self-determination and national sovereignty for the better part of a century. So Fidel Castro happens to be the person who has the capacity to summon and bring to fruition, in culmination, a long historical process. It happens that this process culminates in the early ’60s at the same time that the decolonization of Africa and Southeast Asia and the Middle East is undergoing. And all of a sudden Cuba becomes emblematic of a global phenomenon and that there is—that probably no country in the world bore the imprint of American domination more than Cuba did in the 20th century, and so that—that Fidel Castro, with 6 million other Cubans, assumed the political position of challenging the American presence, of minimizing American influence, of expelling American capital, of breaking diplomatic relations and then withstanding, as your guests have indicated, 60 years of one failed invasion, years of covert operations, multiple assassinations and a highly punitive embargo, speaks to the resolve not only of Fidel Castro, but the resolve of the Cuban people.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Professor Pérez, the dominant discussion in the U.S. corporate media is that he was a dictator, that he was a killer, that he killed many and imprisoned dissidents. Your response to that description?

LOUIS PÉREZ JR.: I don’t know how to respond to that. There is, I think—this is an authoritarian system. This is a system that is not reluctant to use repressive means to maintain power. This is a system that has spawned a fairly extensive intelligence system, surveillance systems. And in many ways, I think Cuba offers us a cautionary tale. For 30, 40, 50 years, Cuba has been under siege from the United States. And once that idea of national security enters into the calculus of governance, you are aware that civil liberties and the freedoms of the press and freedom of political exchange shrink—and we’re experiencing this here since 9/11—so that Cuba becomes a national security state, with justification if one believes that the duty of a government is to protect the integrity of national sovereignty. And so, for 50 years, Cuba, 90 miles away from the world’s most powerful country, struggles to maintain its integrity, its national sovereignty, and in the course of these years increasingly becomes a national security state. Ironically, the United States contributes to the very conditions that it professes to abhor.

AMY GOODMAN: Peter Kornbluh, you had a chance to meet Fidel Castro. I’d also like you to give us a thumbnail sketch, a biography, if you will, of Fidel Castro—where he was born, what were the influences on his life, and how it was, 60 years to the day before he died on Friday, he made that trip, leaving Mexico with Che Guevara and his brother Raúl to begin the Cuban revolution.

PETER KORNBLUH: Well, I did have the extraordinary opportunity to spend some real time, quality time, with Fidel Castro, if you will. We organized two major conferences, one on the 40th anniversary of the Bay of Pigs invasion and one on the 40th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, brought all the surviving Kennedy administration officials to Havana, retired CIA officials, and in the case of the Bay of Pigs invasion, we even brought former members of the CIA-led brigade that had invaded Cuba to sit at a conference room table and discuss this rather extraordinary history with Fidel. And over the course of time, we had four private lunches and two state dinners, and I was able to kind of sit in front of him and listen to the history that he embodied and that he was a part of and that he changed, with the power of his personality and the force of his leadership. And we have lost a historical figure, and with him goes tremendous amount of history that only he knew and only he could share. And so, the movies and the books to come, I think, are going to be extremely important for us to evaluate and think more about the history that he helped to make and dominated, in many ways, over the last 50, 60 years.

You know, he was born to a Spanish immigrant who became a major land owner in the provinces of Cuba. He grew up a relatively privileged life. He became a lawyer. And he began to oppose the Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista, leading a kind of overthrow attempt on July 26, 1953, at the Moncada Barracks. That’s why his movement was called the July 26 Movement. That effort failed miserably, and he was thrown in jail. He miraculously was actually released under an amnesty and exiled to Mexico, where, as we know, he organized the Cuban revolution.

He received a lot of credit for sparking the revolution, but as Lou Pérez would be the first to say, there was tremendous opposition to Batista in the urban sectors, organized independently of Fidel Castro. But his landing in Cuba on December 2nd, 1956, in a small boat, the Granma, with 88 guerrillas to go into the mountains, started kind of the process going forward in a big way. You know, it was an improbable revolution. The landing—the landing party led by Fidel was attacked almost immediately, and he lost the vast majority of his men. Only 12 members of the landing group, the guerrillas that he was bringing to Cuba, survived—among them, him and Raúl and—his brother, and Che Guevara and just a handful of others. And—but he, for the force of his personality, managed to broaden the appeal, hook up with the urban revolutionaries and opposition and bring about this extraordinary revolution.

He survived assassination attempts. He might have actually been killed at the Bay of Pigs; he was—members of the brigade had him in their rifle sights. He survived there. He survived the missile crisis, in which the Kennedy administration was almost ready to obliterate Cuba to take out those Soviet missiles. And along the way, he, you know, turned his country upside down. There’s going to be a lot of debates, and is debate right now, over the legacy of his repression, of his economic decisions. Even he, later in life, acknowledged that the model that he had set forward wasn’t successful in the end for Cubans over the long term.

The Untold Story of Cuba's Support for African Independence Movements Under Fidel Castro

Across the developing world, former Cuban President Fidel Castro was viewed as a hero who stood up to the United States and assisted Marxist guerrillas and revolutionary governments around the world. In the 1970s, he sent Cuban troops to Angola to support a left-wing government over the initial objections of Russia. Cuba helped defeat South African insurgents in Angola and win Namibia’s independence from South Africa in 1990, adding pressure on the apartheid regime. After Nelson Mandela was freed from prison in 1990, he repeatedly thanked Castro. We feature excerpts of Castro speaking about Cuba’s role in Angola and South Africa, including a clip of his first meeting with anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela, and speak with Bill Fletcher, a founder of the Black Radical Congress, and Peter Kornbluh, director of the Cuba Documentation Project and co-author of "Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana."

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to the relationship between Castro and Nelson Mandela—of course, the South African president imprisoned for decades himself. In 1991, a year after he was freed and a few years before he became president, Nelson Mandela visited Cuba to thank President Fidel Castro. This is when they first met.

NELSON MANDELA: Before we say anything, you must tell me when you are coming to South Africa. You see—no, just a moment, just a moment, just a moment.

PRESIDENT FIDEL CASTRO: [translated] The sooner, the better.

NELSON MANDELA: And we have had a visit from a wide variety of people. And our friend, Cuba, which had helped us in training our people, gave us resources to keep current with our struggle, trained our people as doctors, and SWAPO, you have not come to our country. When are you coming?

PRESIDENT FIDEL CASTRO: [translated] I haven’t visited my South African homeland yet. I want it, I love it as a homeland. I love it as a homeland as I love you and the South African people.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Nelson Mandela imploring Fidel Castro to come to South Africa. And this is Fidel Castro speaking in South Africa in 1998.

PRESIDENT FIDEL CASTRO: [translated] Let South Africa be a model of a more just and more humane future. If you can do it, we will all be able to do it.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Fidel Castro speaking in South Africa, and, before that, Nelson Mandela, just after he got out of jail, visiting Castro in Cuba to invite him to South Africa. Bill Fletcher, talk about the relationship of Cuba, Fidel Castro, with the continent of Africa and liberation struggles there.

BILL FLETCHER JR.: Well, you know, it’s interesting, Amy, because there was a special relationship that existed between the Cuban revolution and Africa from almost the beginning. The Cubans were very supportive of the Algerian struggle against the French, which succeeded in 1962. They went on to support the various anticolonial movements in Africa, including in particularly the anti-Portuguese movements in Guinea-Bissau, Angola and Mozambique. And they were unquestioning in their support for the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa.

It’s the Angolan struggle that receives a lot of attention. And one of the things that was not understood at the time by many of us in the United States, including many of us on the left, was that when Cuban troops went to Angola, they did not go at the behest of the Soviet Union. In fact, the Soviet Union was not in favor of Cuban troops going there. The Cubans went there out of a sense of solidarity. I mean, they actually believed in solidarity. And they went there to stop the invasion that was in the process of taking place between—by the South African apartheid troops and their allies in the FNLA and UNITA. And so, this relationship has been very, very strong.

And you could tell in the words of the late President Mandela that this bond, this love for the Cuban people and for the Cuban revolution—that bond also translated into a feeling in black America of a certain kind of bond, a certain support for the Cuban revolution, feeling that this was a revolution that paid attention to Africa but also paid attention to the struggle around racism within Cuba, although, obviously, there were certain limitations to that, but I would say that Cuba probably made the greatest advances in the struggle around racism of any country in the Western Hemisphere.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn Cuba’s role in Angola. This is a clip from the 2001 documentary Fidel: The Untold Story, that was directed by Estela Bravo. You hear the narrator Vlasta Vrana first.

VLASTA VRANA: Right from the beginning, Cuba’s revolutionary ideals not only spread throughout Latin America, but also forged strong ties with national liberation leaders, such as Sékou Touré, Amílcar Cabral, Julius Nyerere, Samora Machel and Agostinho Neto.

PRESIDENT FIDEL CASTRO: [translated] When the regular South African troops invaded Angola, we couldn’t stand by and do nothing. When the MPLA asked for our help, we offered them the help they needed.

VLASTA VRANA: In 1975, as Angola moved towards independence from Portugal, the CIA, along with the apartheid government of South Africa, tried to bring down the new Angolan government. At the request of the Angolan president, Fidel sent 36,000 troops to keep the South African forces from attacking Rwanda, the capital. For many Cubans, whose ancestors were African slaves, the fight in Angola was a way to repair a debt to history. In 14 years of war, over 300,000 Cubans—doctors, teachers and engineers, as well as soldiers—played an important role in Angola. More than 2,000 lost their lives. In 1988, Fidel sent in more Cuban troops for the decisive battle at Cuito Cuanavale and directed operations from Cuba. The defeat of the South African army drove a large nail into the coffin of apartheid and helped advance the struggle of the South African people.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s a clip from the 2001 documentary Fidel: The Untold Story, directed by Estela Bravo. Now let’s go to the film CIA & Angolan Revolution. In this clip, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger explains why the U.S. was concerned about the Cuban troops that Fidel Castro had sent to fight in Angola. After Kissinger, you hear Fidel Castro himself.

HENRY KISSINGER: We thought, with respect Angola, that if the Soviet Union could intervene at such distances, from areas that were far from the traditional Russian security concerns, and when Cuban forces could be introduced into distant trouble spots, and if the West could not find a counter to that, that then the whole international system could be destabilized.

PRESIDENT FIDEL CASTRO: [translated] It was a question of globalizing our struggle vis-à-vis the globalized pressures and harassment of the U.S. In this respect, it did not coincide with the Soviet viewpoint. We acted, but without their cooperation. Quite the opposite.

AMY GOODMAN: That from the film CIA & Angolan Revolution. Bill Fletcher, as we wrap up this section on Cuba in Africa?

BILL FLETCHER JR.: There’s a story that I heard, Amy, about what happened in Angola on the night of independence. And there was panic in the capital. South African troops and their allies were approaching, and no one knew what was going to happen. And then, at midnight, people went down to the docks. And out of the darkness came Cuban troops, Cuban ships, that then landed troops. And the look on the face of the person who told me this story, who witnessed this, was something that I’ll never forget—the sense that they had been saved at a critical moment in an act that had not been driven by the Soviet Union, but had been driven by a belief in solidarity and a particular relationship between Cuba and Africa. And that’s something that the U.S. mainstream media is completely ignoring at this moment.

AMY GOODMAN: And Che Guevara would be in Africa—right?—fighting for—

BILL FLETCHER JR.: Correct.

AMY GOODMAN: —leading Cuban forces, before he would ultimately die in Latin America.

BILL FLETCHER JR.: That’s correct. He went to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and was fighting a neocolonial regime that—ironically, he was working with Kabila, Laurent Kabila, in the beginning. But the forces there were very poorly organized. They weren’t really ready to carry out a revolution, and the Cuban advisers withdrew, ultimately, because the conditions were not right.

AMY GOODMAN: Speaking about Che, I thought I would turn right now to Che Guevara. I want to turn to another clip from the film Fidel: The Untold Story, directed by Estela Bravo. This is Fidel Castro talking about Che Guevara following his execution in Bolivia in 1967.

PRESIDENT FIDEL CASTRO: [translated] I dream about him often. I dream that I’m talking to him, that he’s alive. It’s a very special thing. It’s hard to accept the fact that he’s dead. Why is that? I’d say it’s because he’s always present, always present everywhere.

AMY GOODMAN: In 1997, three decades after he was killed, Che Guevara’s remains were found and returned to Cuba. Fidel Castro talked more about him in the film Fidel.

PRESIDENT FIDEL CASTRO: [translated] I dream about him often. I dream that I’m talking to him, that he’s alive. It’s a very special thing. It’s hard to accept the fact that he’s dead. Why is that? I’d say it’s because he’s always present, always present everywhere.

AMY GOODMAN: That from Fidel, by Estela Bravo. We’re going to go to break and then come back and talk about the effect of Cuba and Fidel Castro and Che Guevara in Latin America. This is Democracy Now!, as we look at the life and legacy of Fidel Castro. He died on Friday at the age of 90. Stay with us.

How Fidel Castro Showed Latin America There was a Way to Resist U.S. Imperialism

As we revisit the life and legacy of former Cuban President Fidel Castro, we examine how Cuba’s revolutionary ideals spread throughout Latin America. The failed invasion of the Bay of Pigs was widely celebrated as the first defeat of imperialism in the Americas, notes Lou Pérez, professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He says, "that victory just reverberated across Latin America and, perhaps more than anything else, suggested that a people resolved, with a leader resolved, with a capacity to resist intervention, perhaps it was indeed possible."

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. We’re hosting a roundtable discussion on Fidel Castro, who died Friday at the age of 90. We’re speaking with Bill Fletcher, who is the founder of the Black Radical Congress, Peter Kornbluh of the Cuba Documentation Project and Professor Lou Pérez Jr., author of Cuba in the American Imagination: Metaphor and the Imperial Ethos.

Professor Lou Pérez Jr., talk about the effect of Fidel Castro in Latin America. We just left this conversation about Che Guevara, his death. Talk about what Che Guevara was doing there, what he was doing for Fidel, and what Fidel—overall, Fidel Castro was doing in Latin America beyond Cuba.

LOUIS A. PÉREZ JR.: The power of Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution stands as a phenomenon of resisting the American pushback against the Cuban revolution. That is, in a region that had been—that had been repeatedly intervened militarily, in Mexico and the Central America—in Central America, political intermeddling, economic intervention in South America. The example of Cuba, especially, I think—especially with the failed invasion of the Bay of Pigs, which contributed powerfully to the consolidation and then centralization of power, and the Cubans celebrated the Bay of Pigs as the first defeat of imperialism in the Americas. And that projection, that boast, that victory, just reverberated across Latin America and, perhaps any—more than anything else, suggested that a people resolved, with a leader resolved, with a capacity to resist intervention, perhaps it was indeed possible. And when the Cubans exhort Latin America to make the Andes the Sierra Maestra of the New World, that idea—that idea of being able to affirm autonomy, agency, self-determination, national sovereignty, just resonated across the Western—across Latin America. And Che Guevara takes the model of the Cuban guerrilla war, the foco theory, the idea that a small handful of people who inter themselves in the interior, the hinterland, of a Latin American country can create what we call the subjective conditions of revolution, and from that guerrilla foco would expand a revolutionary movement that would eventually prevail and proclaim victory. The Che Guevara model of revolution essentially is the replication of the Cuban guerrilla war during the—’57 and ’58.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about what happened with Che Guevara in Bolivia and what that meant to Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution.

Will Trump Roll Back Efforts to Normalize Relations Between Havana & Washington?

President-elect Donald Trump has condemned the thawing of relations between the United States and Cuba, and after the death of leader Fidel Castro, he called him a "brutal dictator who oppressed his own people for nearly six decades." Trump has also vowed to withdraw from diplomatic relations if he believes his new demands go unmet in the future. We speak with Peter Kornbluh, co-author with William LeoGrande of "Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana."

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to today and the response of the U.S. leaders. You had President Obama actually tweeting, I believe, after Donald Trump, the president-elect, did. First he [Trump] tweeted, "Fidel Castro is Dead!" exclamation point, then condemned the late Cuban leader. In a statement issued hours after Castro’s death, the statement read—not clear who wrote it or tweeted it: "[T]he world marks the passing of a brutal dictator who oppressed his own people for nearly six decades. Fidel Castrol’s legacy is one of firing squads, theft, unimaginable suffering, poverty and the denial of fundamental human rights." And then—that was Donald Trump. This is Donald Trump’s senior adviser, Kellyanne Conway.

KELLYANNE CONWAY: We’re allowing commercial aircraft there. We pretend that we’re actually doing business with the Cuban people now, when really we’re doing business with the Cuban government and the Cuban military. He’s been very clear that the major priority now is to make sure Cubans on Cuba have the same freedoms that Cubans here in America have, which is political, religious and economic freedom, make sure those political prisoners are finally released into freedom, and make sure the American fugitives face the law.

AMY GOODMAN: So that’s Kellyanne Conway. Peter Kornbluh, can you respond to her description and also talk about what this means for today, as this all takes place in this period leading into a Donald Trump presidency, and what this means?

PETER KORNBLUH: I can. But let me just follow up on Lou Pérez’s point by saying a very personal anecdote. When news, very early Saturday morning, came in that Fidel Castro had died, I spoke to a very special friend of mine from Peru, and she said to me, "For all—most of my life, he was a hero to me for standing up to the United States." And certainly throughout Latin America and much of the Third World, that, I think, was a prevalent thought about Fidel’s passing. He stood up to the United States. He gave pride, nationalism, self-determination, sovereignty, independence to Cuba, but also created a model and an aspiration for many other peoples and many other countries in the Third World that had been under the thumb of the United States for many years.

You know, we’re in a very delicate moment right now with the election of Donald Trump. Trump, in September, went to Miami and tried to garner hardline Cuban-American votes by saying that he was going to rescind and reverse all of the executive orders that Barack Obama had made to move the process of normalization of relations with Cuba forward, and that he would reverse those, that process, unless the Cubans gave in to our demands, gave in to our—and made concessions to the United States. And I can tell you, from being in Cuba often, that the word "concession" is a true four-letter word in Cuba. It leads to almost an explosive negative reaction, the idea that Cuba would ever make any concessions to the United States. That is the pride they have in their revolution. What Obama has done is not made a bad deal with Cuba. He hasn’t made any deal with Cuba at all. He had said to the Cubans, "We are going to move forward in the interests of U.S. policy, in the interests of our relations with the rest of Latin America and in our own interests that we should have a different relationship with you, and we think it’s going to have an impact on your society, on your economy and on your politics over the long term. But we’re going to move forward towards normal relations, and you can join us if you want, or if you don’t want to, you don’t have to."

And the Cubans have always wanted normal relations with the United States. The secret declassified history of Fidel’s efforts to reach out to the United States, in between speeches denouncing imperialist Yankees, is very clear in the book that Bill LeoGrande and I did, Back Channel to Cuba. Fidel wanted the validation for the Cuban revolution of having a peaceful coexistence with the United States. And as Lou Pérez so importantly pointed out, Cuba preferred not to live in the shadow of the security threat from the colossus of the North. They would much prefer not to have the threat of U.S. intervention hanging over them. And that’s what normal relations would eventually mean to them. And now we have a situation where Trump may want to roll back these great gains, that are happening this very moment with these direct flights to Havana and tens of thousands of Americans going—

AMY GOODMAN: Landing as we speak for the first time, direct flights.

PETER KORNBLUH: Landing as we speak. I mean, this is a dramatic moment, and it’s really the moment in which U.S. citizens and citizens around the world are going to have to really organize to press for a continuation of this very important process of peace and dignity and harmony between the United States and Cuba, which is now being threatened by the position of the incoming president, Donald Trump.

AMY GOODMAN: And your response to the description of Fidel Castro as a brutal dictator, Peter?

PETER KORNBLUH: Well, listen, Fidel Castro was an authoritarian. He ruled with an iron fist. There was repression and is repression in Cuba. In his—in Fidel’s kind of argument, he did it in the name of a different kind of democracy, a different kind of freedom—the freedom from illness, the freedom from racism, the freedom from social inequality. And Cuba has a lot of very positives that all the other countries that we don’t talk about don’t have. There isn’t gang violence in Cuba. People aren’t being slaughtered around the streets by guns every day. They defeated the Zika virus right away. There is universal healthcare and universal education. So, this is the debate over the legacy of Fidel Castro. But the more—

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we’re going to—we’re going to have to leave it there, but I thank you so much for being with us. And then we’ll continue this discussion. Thanks to our guest Peter Kornbluh, director of the Cuba Documentation Project at the National Security Archive, co-author of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana. Thanks to Lou Pérez, professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, author of Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution. And Bill Fletcher, columnist for BlackCommentator.com, founder of the Black Radical Congress.

Headlines:

Fidel Castro, Leader of Cuban Revolution, Dies at 90

The Cuban government has declared nine days of national mourning following the death of Fidel Castro. He died on Friday at the age of 90. His death came 60 years to the day after he, his brother Raúl, Che Guevara and 80 others set sail from Mexico in 1956 to begin what became the Cuban revolution to oust the U.S.-backed Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista. Batista fled the island in 1959, and the Castros have led Cuba ever since. The Cuban revolution would inspire revolutionary efforts across the globe and lead Castro to become one of the archenemies of the United States. It is said he survived over 600 assassination attempts, many orchestrated by the CIA. Across the developing world, Fidel Castro was viewed as a hero who stood up to Washington and offered support for anticolonial struggles. Bolivian President Evo Morales spoke about Fidel Castro on Saturday.

President Evo Morales: "Fidel as a man, Fidel as a brother, a great human being. Fidel as a politician, a great revolutionary. Fidel Castro is a great teacher in principles and values, a teacher of revolutionaries. His fight has not only been for the Cuban people nor for the people of Latin America. The fight of Fidel has been for the people of the world that fought for freedom."

Sello Hatang of the Nelson Mandela Foundation also praised Castro.

Sello Hatang: "To the people of Cuba, your pain is ours. Fidel Castro belonged to you as much as he belonged to us. And we all believe that—we all know that at some point one has to transition to the other world. And I think, in his case, he is a proud man, having helped many struggles around the world to achieve freedom."

In a prepared statement, President Obama said, "History will record and judge the enormous impact of this singular figure on the people and the world around him." Meanwhile, President-elect Donald Trump tweeted, "Fidel Castro is Dead!" He later described Castro as "a brutal dictator who oppressed his own people for nearly six decades."

TOPICS:

Trump Claims Millions of Illegal Voters Cost Him Popular Vote

In political news, President-elect Donald Trump is claiming that millions of people illegally voted in the November 8 election, but offered no evidence to support his claim. On Sunday, Trump tweeted, "In addition to winning the Electoral College in a landslide, I won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally." While Trump did win the Electoral College, Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton’s lead in the popular vote has now reached over 2 million and is expected to grow to 2.5 million.

TOPICS:

Clinton Team Joins Jill Stein Effort for Election Recount

On Saturday, Hillary Clinton’s legal team said it had agreed to participate in a recount of Wisconsin votes after the state’s election board approved the effort requested by Green Party candidate Jill Stein. Stein requested the recount after some computer scientists and election lawyers raised the possibility that hacks could have affected the results.

Dr. Jill Stein: "Today we filed our petition for a recount, a hand recount, of the ballots in the presidential race in the state of Wisconsin. So this is very exciting, because we are standing up as a grassroots campaign and a grassroots movement. We are standing up for a voting system that we deserve, that we can have confidence in, that has integrity and security, and that we know is not subject to tampering, malfeasance, hacking and so on. So we’re standing up to say that we deserve that in this election and actually in every election."

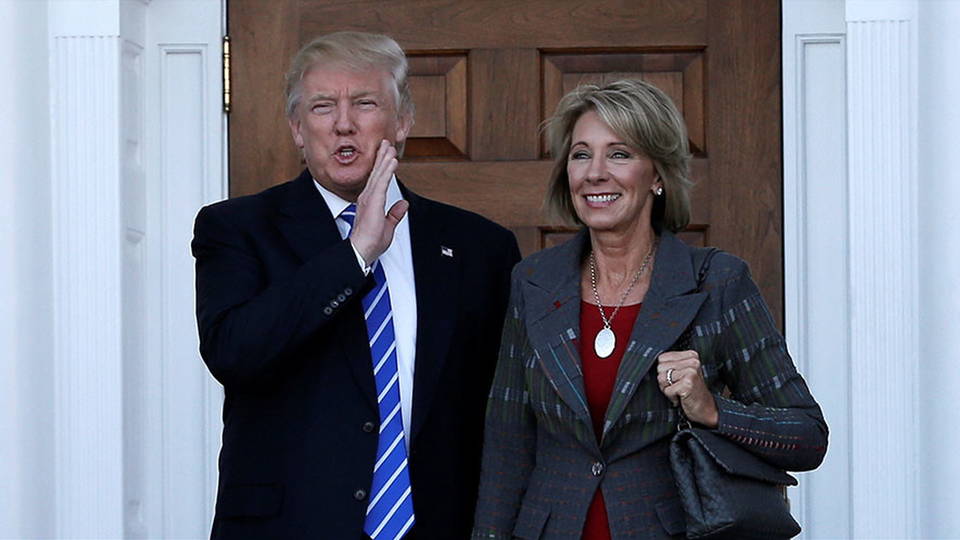

Trump Taps Billionaire Charter School Advocate Betsy DeVos as Education Secretary

Donald Trump has tapped conservative billionaire Betsy DeVos to serve as education secretary. DeVos is the former chair of the Michigan Republican Party and a longtime backer of charter schools and vouchers for private and religious schools. American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten criticized the pick. She said, "In nominating DeVos, Trump makes it loud and clear that his education policy will focus on privatizing, defunding and destroying public education in America." DeVos’s father-in-law is the co-founder of Amway and a longtime supporter of right-wing causes. Her brother is Erik Prince, founder of the mercenary firm Blackwater.

TOPICS:

Israel Praises Nikki Haley Pick as U.N. Ambassador

Donald Trump has named South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley as the next U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. The daughter of Indian immigrants, Haley is widely seen as a foreign policy novice. Israel was one of the first countries to welcome her nomination. Last year, Haley became the first governor to sign legislation against the BDS, or Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions, movement, an international campaign to pressure Israel to comply with international law and respect Palestinian rights.

TOPICS:

Trump Aide Criticizes Romney as Potential Secretary of State Pick

This comes as Donald Trump has yet to announce his pick for secretary of state. Former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney and former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani are said to be in the running. On Sunday, one of Donald Trump’s top advisers, Kellyanne Conway, publicly criticized Romney during an appearance on "Meet the Press."

Kellyanne Conway: "People feel betrayed to think that Governor Romney, who went out of his way to question the character and the intellect and the integrity of Donald Trump, now our president-elect, would be given the most significant Cabinet post of all: secretary of state. And that is a decision that only one man can make."

TOPICS:

Army Corps of Engineers to Close Access to Standing Rock Protest Camp

In news from North Dakota, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has announced it plans to close public access to the site of the Standing Rock protest camp on December 5. For months, indigenous water protectors have camped out in the area to fight the $3.8 billion Dakota Access pipeline, which would carry crude from the Bakken oilfields of North Dakota through South Dakota, Iowa and Illinois. In a statement Sunday, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said it had "no plans for forcible removal" of protesters, but the agency said anyone who remained would be considered unauthorized and could be subject to various citations. Dave Archambault II, the chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, said in a statement that the tribe was "deeply disappointed" by the decision.

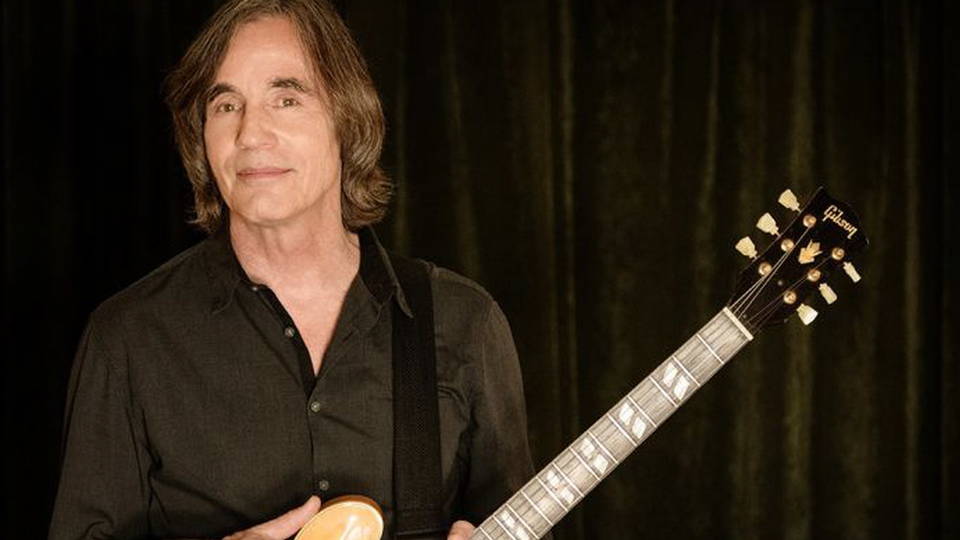

Jackson Browne Plays Anti-DAPL Concert in North Dakota

Meanwhile, on Sunday night, musical legends Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt performed a benefit concert for the Standing Rock protesters. Jackson Browne made headlines last month when he signed an open letter to Kelcy Warren, CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, which owns the pipeline. Warren also owns a small music label, Music Road Records, which once released a Jackson Browne tribute CD. Browne said, "I do not support the Dakota Access pipeline. I will be donating all of the money I have received from this album to date, and any money received in the future, to the tribes who are opposing the pipeline." In the press release about the Jackson Browne tribute album, pipeline owner Kelcy Warren wrote, "I don’t know of anybody that admires Jackson more than me."

U.N.: Half a Million Children Live in Besieged Areas

In news from Syria, the United Nations is warning that about half a million children are now trapped in besieged areas and are "almost completely cut off from sustained humanitarian aid and basic services." The U.N. report estimates there are 100,000 trapped children in the rebel-held areas of Aleppo, which witnessed intense fighting over the weekend. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, two rebel-held areas of eastern Aleppo have fallen to government forces in what’s been described as the biggest defeat for the opposition in Aleppo since 2012.

TOPICS:

Pentagon Reports First U.S. Combat Death in Syria

In other news from Syria, the Pentagon has announced the U.S. military has suffered its first combat death in Syria. The military said a Special Operations Forces member was killed by an improvised explosive device in northern Syria on Thursday.

TOPICS:

Obama Moves to Expand Military Operations in Somalia

With less than two months remaining in office, President Obama has quietly moved to expand U.S. military operations in Somalia. According to The New York Times, the administration has decided to deem the militant group al-Shabab to be part of the armed conflict that Congress authorized after the September 11, 2001, attacks, even though al-Shabab did not exist as an organization at the time. The move will make it easier for U.S. forces to intensify airstrikes and counterterrorism operations.

TOPICS:

Israel Announces Plan to Build 500 New Settlement Homes in Jerusalem

Israel has announced plans to build 500 new settlement homes in occupied East Jerusalem in violation of international law. It is the first announcement of new settlement construction since the election of Donald Trump, who has claimed all of Jerusalem is part of Israel. Palestinian lawmaker Mustafa Barghouti criticized the move.

Mustafa Barghouti: "The declaration of the establishment of 500 new settlement units is only the beginning of a very dangerous step to legalize and build more than 30,000 new settlement units in the area of Jerusalem. More than that, this Israeli government is planning to legalize and initiate 120 new settlements in addition to the 159 settlements."

TOPICS:

47th National Day of Mourning Held on Thanksgiving at Plymouth Rock

On Thursday, an estimated 1,000 indigenous people and allies gathered at Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts, for the 47th National Day of Mourning. This year’s gathering—the largest ever—was held in solidarity with the water protectors at Standing Rock, North Dakota. Speakers included Moonanum James, co-leader of the United American Indians of New England.

Moonanum James: "In the spirit of Crazy Horse, in the spirit of Metacom and in the spirit of Geronimo, but, above all, in the spirit of the water protectors at Standing Rock, and rest assured of this: We are not panicking. We are not conquered. We are as strong as ever. Ho!"

TOPICS:

-------

Donate today:

Follow:

CELEBRATE 20 YEARS OF DEMOCRACY NOW!

Democracy Now!'s 20th Anniversary Celebration

SPEAKING EVENTS

Senior TV Producer

-------

207 West 25th Street, 11th Floor

New York, New York 10001, United States

-------

Democracy Now! Daily Digest: A Daily Independent Global News Hour with Amy Goodman & Juan González for Friday, November 25, 2016

democracynow.org

Stories:

A Tribute to Blacklisted Lyricist Yip Harburg: The Man Who Put the Rainbow in The Wizard of Oz

AMY GOODMAN: Today’s program was actually produced for radio in 1996 with Errol Maitland and Dan Coughlin. Special thanks to Gary Helm, Brother Shine and Julie Drizen. ... Read More →

-------

Donate today:

Follow:

CELEBRATE 20 YEARS OF DEMOCRACY NOW!

Democracy Now!'s 20th Anniversary Celebration

SPEAKING EVENTS

-------

Democracy Now! Daily Digest: A Daily Independent Global News Hour with Amy Goodman & Juan González for Friday, November 25, 2016

democracynow.org

Stories:

A Tribute to Blacklisted Lyricist Yip Harburg: The Man Who Put the Rainbow in The Wizard of Oz

His name might not be familiar to many, but his songs are sung by millions around the world. Today, we take a journey through the life and work of Yip Harburg, the Broadway lyricist who wrote such hits as "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" and who put the music into The Wizard of Oz. Born into poverty on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Harburg always included a strong social and political component to his work, fighting racism and poverty. A lifelong socialist, Harburg was blacklisted and hounded throughout much of his life. We speak with Harburg’s son, Ernie Harburg, about the music and politics of his father. Then we take an in-depth look at The Wizard of Oz, and hear a medley of Harburg’s Broadway songs and the politics of the times in which they were created. [includes rush transcript]

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: Today, we pay tribute to Yip Harburg. His name may not be familiar to many, but his songs are sung by millions around the world, like jazz singer Abbey Lincoln and Tom Waits, Judy Collins, and Dr. John from New Orleans, Peter Yarrow, that’s Al Jolson, and our beloved Odetta.

"Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" may well be a new anthem for many Americans. The lyrics to that classic American song were written by Yip Harburg. He was blacklisted during the McCarthy era. During his career as a lyricist, Yip Harburg used his words to express anti-racist, pro-worker messages. He’s best known for writing the lyrics to The Wizard of Oz, but he also had two hits on Broadway: Bloomer Girls, about the women’s suffrage movement, and Finian’s Rainbow, a kind of immigrants’ anthem about race and class and so much else.

Today, in this Democracy Now! special, we pay tribute to Yip Harburg’s life. Ernie Harburg is Yip’s son and biographer. He co-wrote the book Who Put the Rainbow in The Wizard of Oz?: Yip Harburg, Lyricist. I met up with Ernie Harburg at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center years ago when they are exhibiting Yip Harburg’s work. Ernie Harburg took me on a tour.

ERNIE HARBURG: The first place is business about words, and one of them is that the songs, when they were written back in those days, anyhow, always had a lyricist and a composer, and neither one of them wrote the song. They both wrote the song. However, in the English language, you know, you have "This is Gershwin’s song," or "This is" — they usually say the composer’s song. I’ve rarely ever heard somebody say, "This is Yip Harburg’s song" or "Ira Gershwin’s song." Both of them would be wrong. The fact is, two people write a song.

So I’m going to talk about Yip’s lyrics and then lyrics in the song. Now the first thing we’re looking at here is an expression really of Yip’s philosophy and background, which he brings to writing lyrics for the songs. And what it says here is that songs have always been man’s anodyne against tyranny and terror. The artist is on the side of humanity from the time that he was born a hundred years ago in the dire depths of poverty that only the Lower East Side in Manhattan could have when the Russian Jews, about two million of them, got up out of the Russian’s shadows and ghettos, and the courageous ones came over here and settled in that area of what we now know as the East Village. And Yip knew poverty deeply, and he quoted Bernard Shaw as saying that the chill of poverty never leaves your bones. And it was the basis of Yip’s understanding of life as struggle.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go back to how Yip got his start.

ERNIE HARBURG: Yip was, at a very early age, interested in poetry, and he used to go to the Tompkins Square Library to read, and the librarians just fed him these things. And he got hooked on every one of the English poets, and especially O. Henry, the ending. He always has a little great ending on the end of each of his songs. And he got hooked on W.S. Gilbert, The Bab Ballads.

And then, when he went to Townsend High School, they had them sitting in the seats by alphabetical order, so Yip was "H" and Gershwin was "G", so Ira sat next to Yip. One day, Yip walked in with The Bab Ballads, and Ira, who was very shy and hardly spoke with anybody, just suddenly lit up and said, "Do you like those?" And they got into a conversation, and Ira then said, "Do you know there’s music to that?" And Yip said, "No." He said, "Well, come on home."

So they went to Ira’s home, which was on 2nd Avenue and 5th Street which is sort of upper from Yip’s poverty at 11th and C. And they had a Victrola, which is like having, you know, huge instruments today, and played him H.M.S. Pinafore. Well, Yip was just absolutely flabbergasted, knocked out. And that did it. I mean, for the both of them, because Ira was intensely interested that thing, too.

That began their lifelong friendship. Then Ira went on to be one of the pioneers, with 25 other guys, Jewish Russian immigrants, who developed the American Musical Theater. And it was only after — in 1924, I think, that Ira’s first show with George Gershwin, his brother, that they started writing together.

AMY GOODMAN: The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess in 1940.

ERNIE HARBURG: Yip’s career took a kind of detour, because when the war, World War I, came and Yip was a socialist and did not believe in the war, he took a boat down to Uruguay for three years. I mean, he refused to fight in the thing. That’s shades of 1968 and the Vietnam War, right?

AMY GOODMAN: And why didn’t he believe in World War I?

ERNIE HARBURG: Because he was a full, deep-dyed socialist who did not believe that capitalism was the answer to the human community and that indeed it was the destruction of the human spirit. And he would not fight its wars. And at that time, the socialists and the lefties, as they were called, Bolsheviks and everything else, were against the war.

And so, when he came back, he got married, he had two kids, and he went into the electrical appliance business, and all the time hanging out with Ira and George and Howard Dietz and Buddy De Sylva and writing light verse for the F.P.A Conning Tower. And the newspapers used to carry light verse, every newspaper. There were about twenty-five of them at that time, not two or three now owned by two people in the world, you know. And they actually carried light verse. Well, Yip and Ira and Dorothy Parker, the whole crowd, had light verse in there, and, you know, they loved it.

So, when the Crash came and Yip’s business went under, and he was about anywhere from $50,000 to $70,000 in debt, his partner went bankrupt. He didn’t. He repaid the loans for the next 20 or 15 years, at least. Ira and he agreed that he should start writing lyrics.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s talk about what Yip is most known for: Finian’s Rainbow, The Wizard of Oz. Right here, what do we have in front of us?

ERNIE HARBURG: We have a lead sheet. We are in the gallery of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and there’s an exhibition called "The Necessity of Rainbows," which is the work of Yip Harburg. And we are looking at the lead sheet of "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" which came from a review called Americana, which—it was the first review, which was—had a political theme to it: at that time, the notion of the forgotten man. You have to remember what the Great Depression was all about. It’s hard to imagine that now. But when Roosevelt said, "One-third of the nation are ill-clothed, ill-housed and ill-fed," that’s exactly what it was. There was at least 30 percent unemployment at those times. And among blacks and minorities, it was 50, 60 percent. And there were breadlines and—

Now, the rich, you know, kept living their lifestyle, but Broadway was reduced to about 12 musicals a year from prior, in the '20s, about 50 a year, OK? So it became harder. But the Great Depression was deep down a fact of life in everybody's mind. And all the songs were censored—I use that loosely—by the music publishers. They only wanted love songs or escape songs, so that in 1929 you had "Happy Days Are Here Again," and you had all of these kinds of songs. There wasn’t one song that addressed the Depression, in which we were all living. And this show, the Americana show, Yip was asked to write a song or get the lyrics up for a song which addressed itself to the breadlines, OK?

And so, he, at that time, was working very closely with Jay Gorney. Jay had a tune, which he had brought over with him when he was eight years old from Russia, and it was in a minor key, which is a whole different key. Most popular songs are in major. And it was a Russian lullaby, and it was da, da, da, da, da, da, da, da, da. And Jay had — somebody else had lyrics for it: "Once I knew a big blonde, and she had big blue eyes. She was big blue" — like that. And it was a torch song, of which we talked about. And Yip said, "Well, could we throw the words out, and I’ll take the tune?" Alright.

And if you look at Yip’s notes, which are in the book that I mentioned, you’ll see he started out writing a very satiric comedic song. At that time, Rockefeller, the ancient one, was going around giving out dimes to people, and he had a—Yip had a satiric thing about "Can I share my dime with you?" You know? But then, right in the middle, other images started coming out in his writings, and you had a man in a mill, and the whole thing turned into the song that we know it now, which is here and which I can read to you. And if you do this song, you have to do the verse, because that’s where a lot of the action is.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you sing it to me?

ERNIE HARBURG: Alright, I’ll try. It won’t be as good as Bing Crosby or Tom Waits.

[singing] They used to tell me

I was building a dream,

And so I followed the mob,

When there was earth to plow

Or guns to bear,

I was always there

Right on the job.

They used to tell me

I was building a dream,

With peace and glory ahead,

Why should I be standing in line,

Just waiting for bread?

YIP HARBURG: [singing] Once I built a railroad

I made it run,

Made it race against time.

Once I built a railroad;

Now it’s done.

Buddy, can you spare a dime?

AMY GOODMAN: Yip Harburg singing in 1975.

YIP HARBURG: [singing] Once I built a tower

To the sun,

Brick and rivet and lime;

Once I built that tower;

Now it’s done.

Brother, can you spare a dime?

AMY GOODMAN: When was this song first played?

ERNIE HARBURG: In 1932. And in the Americana review, every critic, everybody took it up, and it swept the nation. In fact, paradoxically, I think Roosevelt and the Democratic Party really wanted to tone it down and keep it off the radio, because playing havoc with trying to not talk about the Depression, which everybody did. You remember the Hoover thing, not only "Happy Days Are Here Again," but "Two Chickens in Every Pot," and so forth. Nobody wanted to sing about the Depression either, you know.

AMY GOODMAN: Yet, Yip Harburg was a supporter of FDR.

ERNIE HARBURG: Yes. But politics are politics, you know, and the thing was that, in fact, historically, this was, I would say, the only song that addressed itself seriously to the Great Depression, the condition of our lives, which nobody wanted to talk about and nobody wanted to sing about.

AMY GOODMAN: Ernie Harburg, son of Yip Harburg. When we come back from our break, we’ll talk about The Wizard of Oz, Finian’s Rainbow and other shows.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We continue with our Democracy Now! special, on our journey of Yip Harburg’s life with his son, Ernie Harburg. Ernie talks about how Yip Harburg wrote the lyrics to The Wizard of Oz.

ERNIE HARBURG: Actually, Yip did more than the lyrics. When they were—when Yip and Harold Arlen were called in to do the score of The Wizard of Oz, it was Yip who had this executive experience in his electrical appliance business and also had become a show doctor, so he was—that is, when a show wasn’t working, you would call somebody and try to fix it up. He had an overview of shows and he had an executive talent. And so, he was always what they called a "muscle man" in a show, alright? And he’d already worked with Bert Lahr in a great song, "The Woodchopper’s Song," and—

AMY GOODMAN: Wait a second. Bert Lahr, the lion?

ERNIE HARBURG: The lion. Bert Lahr and most of these people were from vaudeville and burlesque. And Yip knew them in the ’20s, but he actually worked with Bert Lahr in this light — Walk a Little Faster and another review. I forget that name, but he and—Yip and Arlen gave Bert songs to sing, which allowed him to satirize the opera world, if you want, or a send-off of rich, you know. And so, they had that relationship.

Also, Yip knew Jack Haley, the tin woodman. And Yip also worked with Bobby Connolly as a choreographer in the early '30s on his shows, who was also the choreographer for The Wizard of Oz. So he had a cast here with Arlen who were, you know, sort of Yip's men. You know what I mean? So, when Yip went to Arthur Freed, the producer, who was too busy to work on this musical, and Mervin LeRoy had nothing to do with it, practically, because he had never done a musical before, so it became a vacuum in which the lyricist entered, because he was all ready to do so. Yip was always an active, you know, organizer.

And so, the first thing he suggested was that they integrate the music with the story, which at that time in Hollywood they usually didn’t do. They’d stop the story, and you’d sing a song. They’d stop the story and sing a song. That you integrate this—Arthur Freed accepted the idea immediately. Yip then wrote—Yip and Harold then wrote the songs for the 45 minutes within a 110-minute film. The munchkin sequence and into the Emerald City and on their way to the wicked witch, when all the songs stopped, because they wouldn’t let them do anymore. OK? You’ll notice then the chase begins, you see, in the movie.

AMY GOODMAN: Why wouldn’t they let them do anymore?

ERNIE HARBURG: Because they didn’t understand what he was doing, and they wanted a chase in there. So, anyhow, Yip also wrote all the dialogue in that time and the setup to the songs, and he also wrote the part where they give out the heart, the brains and the nerve, because he was the final script editor. And there was eleven screenwriters on that. And he pulled the whole thing together, wrote his own lines and gave the thing a coherence and a unity, which made it a work of art. But he doesn’t get credit for that. He gets "lyrics by E.Y. Harburg," you see? But, nevertheless, he put his influence on the thing.

AMY GOODMAN: Who wrote The Wizard of Oz originally, the story?

ERNIE HARBURG: Yeah, Frank L. Baum was an interesting kind of maverick guy, who at one point in his life was an editor of a paper in South Dakota. And this was at the time of the Populist revolutions or revolts, or whatever you want to call it, in the Midwest, because the railroads and the eastern city banks absolutely dominated the life of the farmers, and they couldn’t get away from the debts that were accumulated from these. And Baum set out consciously to create an American fable so that the American kids didn’t have to read those German Grimm fairy stories, where they chopped off hands and things like that. You know, he didn’t like that. He wanted an American fable.

But it had this underlay of political symbolism to it that the farmer—the scarecrow was the farmer. He thought he was dumb, but he really wasn’t; he had a brain. And the tin woodman was the result—was the laborer in the factories. With one accident after another, he was totally reduced to a tin man with no heart, alright, on an assembly line. And the cowardly lion was William Jennings Bryan, who kept trying—was a big politician at that time, promising to make the world over with the gold standard, you know? And the wizard, who was a humbug type, was the Wall Street finances, and the wicked witch was probably the railroads, but I’m not sure. Alright?

So it was a beautiful match-up here with Frank Baum and Yip Harburg, OK, because in the book, the word "rainbow" was never once mentioned. And you can go back and look at it. I did three times. The word "rainbow" is never once mentioned in the book. And the book opens up with Dorothy on a black-and-white world, that Kansas had no color. Just read the first paragraph in it.

So, when they got to the part where they had to get the song for the little girl, they hadn’t written it yet. They had written everything else. They hadn’t written the song for Judy Garland, who was a discovery by one of Yip’s collaborators, Burton Lane. And nobody knew the wonder in her voice at that time. So they worked on this song, and at that time, Ira, Yip, Larry Hart and the others thought that the composer should create the music first. Now, they were both locked into—the lyricist and the composer were locked into the storyline and the character and the plot development. So they both knew that at this point there was a little girl in trouble on the Kansas City environment, alright, and that she yearned to get out of trouble, alright? So Yip gave Harold what they call a "dummy title." It’s not the final title, but it’s something that more or less zeroes in on what the situation is all about and what—this little girl is going to take a journey, alright? So Yip gave him a title: "I Want to Get on the Other Side of the Rainbow."

YIP HARBURG: Now, here’s what happened, and I want you to play this symphonically! OK, I said, "My god, Harold! This is a 12-year-old girl wanting to be somewhere over the rainbow. It isn’t Nelson Eddy!" And I got frightened, and I said, "I don’t—let’s save it. Let’s save it for something else. But don’t—let’s not have it in." Well, he felt—he was crestfallen, as he should be. And I said, "Let’s try again." Well, he tried for another week, tried all kinds of things, but he kept coming back to it, as he should have. And he came back, and I was worried about it, and I called Ira Gershwin over, my friend. Ira said to him, he said, "Can you play it a little more in a pop style?" And I played it, with rhythm.

OK, I said, "Oh, well, that’s great. That’s fine." I said, "Now we have to get a title for it." I didn’t know what the title was going to be. And when he had [sings] dee-da-dee-da-da-da-da, [talking] I finally came to the thing, the way our logic lies in it, "I want to be somewhere on the other side of the rainbow." And I began trying to fit it: "On the other side of the rainbow." When he had a front phrase like daa-da-da-da-da — now, if you say "eee," you couldn’t sing "eee-ee." You had to sing "ooooh." That’s the only thing that would get a—and I had to get something with "oh" in it, see: "Over the rain" — now, that sings beautifully, see. So the sound forced me into the word "over," which was much better than "on the other side."

JUDY GARLAND: [singing] Somewhere over the rainbow

Way up high,

There’s a land that I heard of

Once in a lullaby.

ERNIE HARBURG: Anyhow, Yip—Arlen worked on it. He came up with this incredible music, which, if anybody wants to try it, just play the chords alone, not the melody, and you will hear Pachelbel, and you will hear religious hymns, and you will hear fairy tales and lullabies, just in the chords. No one ever listens to that, but try it, if you play the piano.

And at any rate, on top of these chords, then Harold started the thing off with an octave jump: "Somewhere" — OK, and Yip had no idea what to do with that octave jump. Incidentally, Harold did this in Paper Moon, too, if you remember. Let’s see how did that start?

YIP HARBURG: [singing] It’s only a paper moon

Sailing over a cardboard sea

But it wouldn’t be make-believe

If you believed in me

ERNIE HARBURG: And Harold was a great composer. So Yip wrestled with it for about three weeks, and finally he came up with the word. You see, this is what a lyricist does: the word, to hit the storyline, the character, the music. It’s an incredible thing. "Some-where." Alright, and then when you put in an octave, you get "some-where," OK, and you jump up, and you’re ready to take that journey. Alright? Where? "O-ver the rainbow." OK? And then you’re off!

It’s not a love song. It’s a story of a little girl that wants to get out. She’s in trouble, and she wants to get somewhere. Well, the rainbow was the only color that she’d see in Kansas. She wants to get over the rainbow. But then, Yip put in something which makes it a Yip song. He said, "And the dreams you dare to dream really do come true." You see? And that word "dare" lands on the note, and it’s a perfect thing, and it’s been generating courage for people for years afterwards, you know?

JUDY GARLAND: [singing] Somewhere over the rainbow

Skies are blue,

And the dreams that you dare to dream

Really do come true.

ERNIE HARBURG: That’s the way that the whole score came.

AMY GOODMAN: Was it a hit right away?

ERNIE HARBURG: No, it wasn’t. This was supposed to be an answer, MGM’s answer to Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, and of about 10 major critics at that time when The Wizard of Oz came out, I would say only two liked the show. The other eight said it was corny, that it was heavy, that Judy Garland was no good, and so forth. Oh, yeah. You could read again in the book, Who Put the Rainbow on The Wizard of Oz?, by Harold Meyerson and Ernie Harburg. But it persisted, you know? And then, in 1956, when television first started saturating the nation—

AMY GOODMAN: More than 20 years later.

ERNIE HARBURG: More than 20 years later. I don’t think they even had their money back from the show, see? MGM sold the film rights to CBS, who then put it on. And it hit the top of the—it broke out every single record there was, and it’s been playing every year since then. And, of course, it went around the world, and it’s become a major artwork, which is, I must say, an American artwork, because the story, the plot with the three characters, the brain, the heart, the courage, and finding a home is a universal story for everybody. And that’s an American kind of a story, alright? And Yip and Harold put these things into song.

AMY GOODMAN: Who did the munchkins represent?

MUNCHKINS: [singing] We represent the Lollipop Guild

The Lollipop Guild, the Lollipop Guild.

And in the name of the Lollipop Guild...

ERNIE HARBURG: Oh, you mean political thing? I think they represent the little people, you know, the people. And that’s they way they were—it came on in the book. You see, the book, if you’re a purist, you wouldn’t like the film. It’s just like anything else. There are societies of people who meet and discuss the books. OK, there’s even a society for the winkies, which are the guards around the wicked witch’s, you know, castle. There really is! They meet once a year. And they’re serious! They don’t like the picture, because it didn’t follow the book, see, because Yip and the writers changed it, as Hollywood will.

AMY GOODMAN: Was the book a little bit more favorable to the winkies?

ERNIE HARBURG: No—well, yes! The winkies were good people, and they were played up there. If you go back and read the book, you will see that they were a lovely, decent kind of people, yes. That was one thing. I guess it wasn’t PC there, you know?

But, nevertheless, when you read a good novel, and you see the film, there’s hardly any relationship between the two. All these lines from the film have entered the American language in a way that people don’t even know where they came from. You know, "Gee, Toto, looks like we’re not in Kansas anymore." Or, you know, "Come out, come out, wherever you are," which in the ’70s started taking on, when the gay movement started, this line started meaning different things, you see?

GLINDA: [singing] Come out, come out, wherever you are

And meet the young lady, who fell from a star.

ERNIE HARBURG: So the songs keep growing with the times. People interpret them, you know?

AMY GOODMAN: How did Yip feel in the late 1950s, when it was a hit, when people started hearing it all over the world?

ERNIE HARBURG: Well, I think they were quite surprised, along with the film moguls, you know, and the fact that—years and years later, he and Harold both said that they did not know what depth and strength that that song "Over the Rainbow" had. And also, one other one, the song "Ding! Dong! The Witch Is Dead" is a universal liberation, a freedom, cry for freedom, you know, which isn’t seen like that, but it—one time, when some tyrannical owner of an airlines company stepped down, all the employees started singing "Ding! Dong! The Witch Is Dead."

So people use these words. And during the war, World War II, "We’re Off to See the Wizard" was sung by troops marching, you know? But nobody knows that Yip wrote the words, you see. Now, Harold wrote the music, and the songs were Yip and Harold. That’s it.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. If you’d like a copy of today’s show, you can go to our website at democracynow.org. Back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We continue on our tour through the life of lyricist Yip Harburg with his son Ernie Harburg.

ERNIE HARBURG: We’re walking through the gallery here at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, which has "The Necessity of Rainbows," dedicated to the works of Yip Harburg, the lyricist. And we’re now looking at the various exhibitions.

And while we’re looking for Finian’s Rainbow, I want to tell you that in 1944, Yip conceived and co-wrote the script and put on a show called Bloomer Girl, which was way ahead of its time, because Bloomer Girl was Dolly Bloomer, who was an actual suffragette in 1860 who stood up and invented pants. And it was radical in those days. And the show was about Dolly Bloomer, and she ran an underground railroad, bringing slaves up, and she had an underground paper, and she was an incredible woman. And this was a political show. Some great songs in there. Maureen McGovern does "Right as the Rain" in a great way. Lena Horne does "Eagle and Me," which was the first song on Broadway that wasn’t a blues lamentation about the black-white situation. It was a call to action. "We gotta be free, the eagle and me." OK? And Dooley Wilson, who was in Casablanca, sang that.

So, again, Yip managed to get his philosophy into his show, which was the second truly integrated American musical after Oklahoma. And while, you know, it hasn’t been played around, it’s still marked that historically. After that came Finian’s Rainbow.

AMY GOODMAN: You mean blacks and whites playing in the cast.

ERNIE HARBURG: No, not in there. In Finian’s Rainbow, I mean that it was a political statement. Bloomer Girl was a political statement, and it was a smash hit. In 1946, Yip conceived the idea, the story, the script for Finian’s Rainbow, which was meant to be an anti-racist and, in a certain sense, anti-capitalist show also.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s find it.

ERNIE HARBURG: Alright, let’s go.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s find Finian’s Rainbow.

ERNIE HARBURG: Here’s Cabin in the Sky, which is the first all-black Hollywood film in the '40s, which Yip and Harold did also. "Happiness Is Just a Thing Called Joe." Here's Bloomer Girl that I’m talking about. So, we should be, somehow, coming onto Finian’s Rainbow. But here’s Yip here. There’s a video of Yip talking, if you want to meet the man.

INTERVIEWER: You got into political trouble in this country at a time when a lot of people got into political trouble, during the McCarthy years. Were you blacklisted?

YIP HARBURG: Thank God, yes.

INTERVIEWER: During that McCarthy period, were they actually going through your lyrics with a fine-toothed comb looking for lines that might be subversive, that might show Yip Harburg’s true political colors?

YIP HARBURG: Yes. I wrote a song for Cabin in the Sky, which Ethel Waters sang and was part of the situation in the picture. Here was a poor woman who had nothing in life except this one man, Joe, and she sang, "It seemed like happiness is just a thing called Joe."

One of the producers, with not a macroscope, but a microscope, found in this lyric that "Happiness Is Just a Thing Called Joe" was a tribute to Joe Stalin. We’re kidding about it now, but the country, this was the blackest, the blackest and darkest moment in the history of this beautiful country.

ERNIE HARBURG: Now, here we are at Finian’s Rainbow at last. And this was—Yip conceived this in 1946. And Fred Saidy, who was his co-script writer—and Harold Arlen demurred from writing this, because he felt that Yip was too fervent in his political opinions, and he wanted—Harold wanted to do something else. So Yip got Burt Lane and then came out with this great, great score from Finian’s Rainbow, "Old Devil Moon."

"How Are Things in Glocca Morra?" etc. But the theme of Finian’s was a total fantasy, and it was an American fable in which an Irishman and his daughter come from Ireland, search around and find Rainbow Valley in "Missitucky." OK? And he believes that if he plants the crock of gold, which he stole from the leprechaun, in the ground, that it will grow, just like at Fort Knox, right? The whole thing was fabulous!