Lausanne Global Analysis · November 2017

Welcome to the November issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis, which is also available in Portuguese and Spanish. This issue is our 30th and also marks the 5th anniversary of our launch. We look forward to your feedback on it.In this issue we mark the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation with a call to Christian unity for the sake of the Great Commission; we consider how to stimulate theological resource-sharing between North and South; we address the issue of connecting across generations for global mission, drawing on lessons from the Lausanne Younger Leader initiatives; we suggest five simple truths for contemporary church planters; and we briefly review the new Operation World app which helps us to pray purposefully together for the world.

November 2017 Issue Overview

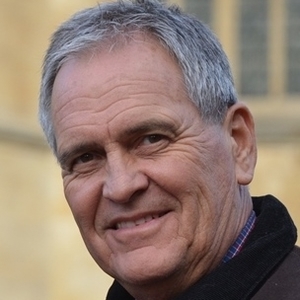

November 2017 Issue OverviewDavid Taylor

Welcome to the November issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis, which is also available in Portuguese and Spanish. This issue is our 30th and also marks the 5th anniversary of our launch. We look forward to your feedback on it.

In this issue we mark the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation with a call to Christian unity for the sake of the Great Commission; we consider how to stimulate theological resource-sharing between North and South; we address the issue of connecting across generations for global mission, drawing on lessons from the Lausanne Younger Leader initiatives; we suggest five simple truths for contemporary church planters; and we briefly review the new Operation World app which helps us to pray purposefully together for the world.

‘What exactly . . . might it mean for Protestants, and especially evangelical Protestants, to recognize the tragic dimensions of the Reformation?’, asks Thomas Albert (‘Tal’) Howard (Professor of Humanities and History at Valparaiso University). With the good outcomes from the Reformation came many undesirable things as well. Notably Christian disunity remains a massive impediment to the gospel itself—the proclamation of which is and should be evangelicalism’s strong suit. Scripture combines evangelical and ecumenical import. Sadly, church history in the post-Reformation era bears ample witness to the gospel-stifling role of Christian disunity. Evangelicals cannot walk away from Christ’s command that we all be one. Those who care about the Great Commission should at least make efforts to become more zealously embarrassed and saddened by church divisions. Yet embarrassment and sadness should not lead to despair. For it is often in our very weakness that Christ’s power can shine forth all the more. ‘Perhaps, . . . in our very weakness, in the very things that should embarrass and sadden us, our Lord—500 years after the Reformation—can still manifest his power in our faults, and look on us with undeserved mercy to do his work, somehow, despite the lacerations that we have caused in his Bride, the church’, he concludes.

‘A key dilemma faced by theological educators is that, whereas most students are in the South, many of the resources are in the North’, writes Kirsteen Kim (Professor of Theology and World Christianity in the School of Intercultural Studies, Fuller Theological Seminary, USA). There is an imbalance between South and North in theological education that needs addressing. When we learn through our theological education to value the whole church, we will realize the importance of resource sharing. There are some great examples of sharing of both human resources and learning resources. Some projects not only share Northern resources with the South but also make Southern resources available globally, including in the North. This is another necessary part of correcting the imbalance in theological education. However, many Northern theologians do not yet recognize their need of reading insights from the South. This is their loss. The technologies are there to facilitate global theological resource sharing. There is a way but what is needed is a will. Resource sharing between North and South is not another means by which the former can help the latter ‘develop’ but a reciprocal activity with mutual benefits. It is missional theological education that values the whole church, which is the key to unlocking theological resource sharing between North and South’, she concludes.

‘Connecting missional leaders across generations is both historically and strategically at the heart of the Lausanne Movement’, write Lars Dahle and Rudolf Kabutz (Lausanne Catalysts for Media Engagement) along with Nana Yaw Offei Awuku (Lausanne Global Associate Director for Generations). The Younger Leaders (YL) initiatives within the movement provide key lessons for the global church. ‘Passing the torch’ of leadership to the next generation was a key concern at the first Younger Leaders’ Gathering (YLG) in Singapore in 1987, thus modelling the missional significance of intergenerational partnerships and friendships for the global church. Christ-like servant leadership across generations was a central theme at Malaysia 2006, thus demonstrating the missional significance of character and partnership to the global church. Learning from the biblical story and from one another’s stories were key themes at Jakarta 2016, thus exhibiting a forward-looking intergenerational missional learning community to the global church. YLGen, launched in 2016, models intergenerational missional discipleship and partnership to the global church. The article concludes with five key lessons for the global church from these initiatives. ‘A deep and prayerful implementation of these five lessons will equip the global body of Christ across generations of younger and experienced leaders to bear witness to Jesus Christ and all his teaching—in every nation, in every sphere of society, and in the realm of ideas’, they conclude.

Data from surveys and discussions organized by the Lausanne Church Planting Issue Network reveal a universal interest in planting healthy churches, as well as challenges common to church planters the world over. ‘After much sifting and reflection, we condensed this collective knowledge into Five Simple Truths about planting churches in the early twenty-first century, hoping to spark yet more discussion on the issues’, write Ron Anderson (Lausanne Catalyst for Church Planting) and Dave Miller (Church of God missionary to Bolivia). The most urgent challenge we face is to make disciples of the next generation. The good news is that young people are more interested than ever in knowing Jesus and becoming his enthusiastic followers if introduced to the gospel. Secondly, we must learn and follow basic biblical ecclesiology. The third simple truth is that every Christian is part of the universal priesthood of believers, and shares its responsibility and authority. Fourthly, Christians must collaborate with each other to impact the world. Finally, networks build unity in the Body of Christ. If church planting is to be effective in the twenty-first century, church planters must obey Jesus’ first century mandate to ‘make disciples of all nations’. ‘This’, they conclude, ‘is the simplest truth of all about church planting’.

‘We have more access to information today than ever before, but it seems harder than ever to discern the truth of what is happening in our big, wide, world’, writes Jason Mandryk (author of Operation World). It is a full-time job just filtering through noise, parsing the agendas, and finding out about more neglected areas and issues. The recently released Operation World app is a useful tool for believers who care about our world. Anyone with an Android or Apple internet-enabled device, anywhere, can use the app for free. It should be a useful source of prayer material for people and places where there is little available. Every day there is just one prayer point for one nation or region. When you pray, you are joining with many thousands of others, around the world, praying for the same thing. Operation World has researched every country so that it can mobilize the body of Christ to pray for what matters most. It sees intercession as the means to unleash the inestimable power of God into our broken world, bringing redemption, reconciliation, and healing. ‘Why not download the app, and join us and thousands of others in our journey of praying for the world?’, he concludes.

We hope that you find this issue stimulating and useful. Our aim is to deliver strategic and credible analysis, information and insight so that as a leader you will be better equipped for the task of world evangelization. It’s our desire that the analysis of current and future trends and developments will help you and your team make better decisions about the stewardship of all that God has entrusted to your care.

Please send any questions and comments about this issue to analysis@lausanne.org. The next issue of The Lausanne Global Analysis will be released in January.

David Taylor serves as the Editor of the Lausanne Global Analysis. David is an international affairs analyst with a particular focus on the Middle East. He spent 17 years in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, most of it focused on the Middle East and North Africa. After that he then spent 14 years as Middle East Editor and Deputy Editor of the Daily Brief at Oxford Analytica. David now divides his time between consultancy work for Oxford Analytica, the Lausanne Movement and other clients, also working with Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), the Religious Liberty Partnership and other networks on international religious freedom issues.

David Taylor serves as the Editor of the Lausanne Global Analysis. David is an international affairs analyst with a particular focus on the Middle East. He spent 17 years in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, most of it focused on the Middle East and North Africa. After that he then spent 14 years as Middle East Editor and Deputy Editor of the Daily Brief at Oxford Analytica. David now divides his time between consultancy work for Oxford Analytica, the Lausanne Movement and other clients, also working with Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), the Religious Liberty Partnership and other networks on international religious freedom issues.

---

A Call to Christian Unity for the Sake of the Great Commission - The 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation

A Call to Christian Unity for the Sake of the Great Commission - The 500th anniversary of the Protestant ReformationThomas Albert Howard

How ought one to commemorate the recent 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, generally held to have begun when Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses on October 31, 1517?

In our recent edited book, Protestantism after 500 Years,[1] my co-editor, Mark Noll, and I argued that a phrase of the late dean of American church historians, Jaroslav Pelikan, resonates at this milestone. For the interests of truth and Christian unity to be served in remembering the Reformation, Pelikan once asserted that Protestants and Catholics should think of the Reformation as a ‘tragic necessity’. Partisans on both sides, Pelikan elaborated, will have difficulty acknowledging this:

In our recent edited book, Protestantism after 500 Years,[1] my co-editor, Mark Noll, and I argued that a phrase of the late dean of American church historians, Jaroslav Pelikan, resonates at this milestone. For the interests of truth and Christian unity to be served in remembering the Reformation, Pelikan once asserted that Protestants and Catholics should think of the Reformation as a ‘tragic necessity’. Partisans on both sides, Pelikan elaborated, will have difficulty acknowledging this:- Roman Catholics agree that it was tragic, because it separated many millions from the true church; but they cannot see that it was really necessary. Protestants agree that it was necessary, because the Roman church was so corrupt; but they cannot see that it was such a tragedy after all.[2]

With October 31, 2017 in mind, Noll and I argued that Catholics should try to reckon with why Protestants, then and now, felt the Reformation was necessary, while Protestants of all denominations are duty-bound to grapple with the tragic dimensions of the Reformation. Or, as the theologian Stanley Hauerwas has put it, ‘if we no longer have broken hearts at the church’s division, then we cannot help but unfaithfully celebrate [the] Reformation.’[3]

WITH THE GOOD OUTCOMES THAT RESULTED FROM THE REFORMATION CAME MANY UNDESIRABLE ONES: BITTER POLEMICS, RELIGIOUSLY MOTIVATED WARFARE, DESTRUCTIVE ICONOCLASM, CONFESSION-INSPIRED EXECUTIONS, AND MORE

However, what exactly—if I may press the question—might it mean for Protestants, and especially evangelical Protestants, to recognize the tragic dimensions of the Reformation? What is at stake theologically? And what might this mean for the Great Commission?For those who know their church history, identifying tragic aspects of the Reformation will perhaps come easily, for with the good outcomes that resulted from the Reformation came many undesirable ones: bitter polemics, religiously motivated warfare, destructive iconoclasm, confession-inspired executions, and more. The very word ‘Protestant’ first appeared to designate a military alliance in 1529. As we prepare to commemorate the Reformation’s quincentennial, we might do well then to remember the Swiss humanist Sebastian Castellio’s pithy line: ‘To kill a man is not to defend a doctrine. It is to kill a man.’[4]

Furthermore, there was Luther’s brutal Anti-Semitism, and his excoriating treatment of peasants, spiritualists, Anabaptists, and Ottoman Turks; and this is to say nothing of the escalation of rhetoric against the Pope as the Antichrist—rhetoric readily reciprocated from the Catholic side—that has poisoned Protestant-Catholic relations for centuries.

Christian disunity as impediment

However, there are additional reasons for recognizing the tragic dimensions of the Reformation. Namely, Christian disunity is and remains a massive impediment to the gospel itself—the proclamation of which is and should be evangelicalism’s strong suit. Scripture combines evangelical and ecumenical import. As our Lord prays for his disciples in his so-called high-priestly prayer,[5]

CHRISTIAN DISUNITY IS AND REMAINS A MASSIVE IMPEDIMENT TO THE GOSPEL ITSELF.

‘I do not pray for these only, but also for those who believe in me through their word, that they may all be one; even as thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that thou hast sent me. The glory which thou hast given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one, I in them and thou in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that thou hast sent me and hast loved them even as thou hast loved me’ (John 17:20-23).[6]Or, as Paul writes to the Corinthians, ‘I appeal to you, brothers and sisters, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that all of you agree with one another in what you say and that there be no divisions among you, but that you be perfectly united in mind and thought’ (1 Cor 1:10). Such admonitions recur in Paul’s letters and in early patristic literature.

Sadly, church history in the post-Reformation era bears ample witness to the gospel-stifling role of Christian disunity. Here are a few examples:

- The jealousy and rivalry between (Catholic) Portuguese missionaries and (Protestant) Dutch ones was one factor that led to the outlawing of Christianity in the 1600s in Japan and the massive persecution of Japanese converts, as shown in Shusaku Endo’s book, Silence.[7]

- Before the founding of the state of Israel, the Ottoman Empire found great amusement in having to keep guards stationed at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, just to keep divided Christians from coming to blows with one another—at the very site where tradition holds that Christ was crucified!

- In our own time, when churches attempt to speak out on painful, contested social and political issues, as mutually antagonistic denominations, they often only succeed in canceling each other out, depriving the public realm of a robust, compelling Christian witness.

Of course, Protestants have often recognized the scandal of disunity and sought to remedy it. In the late nineteenth century, many Protestant missionary bodies became despondent over the fact that their competition and in-fighting meant taking a divided gospel to non-Western peoples. Overcoming this situation, in fact, was the main impulse behind the famous Edinburgh Missionary Conference of 1910.[9] A key commission at this conference was entitled ‘Co-operation and the Promotion of Unity’. The report of this commission lamented Christian divisions and stated that ‘for the achievement of the ultimate and highest end of all missionary work in . . . non-Christian lands of Christ’s one Church—real unity must be attained.’[10] This sentiment gave birth to the modern ecumenical movement—a movement of far-reaching significance in twentieth-century church history.

Of course, Protestants have often recognized the scandal of disunity and sought to remedy it. In the late nineteenth century, many Protestant missionary bodies became despondent over the fact that their competition and in-fighting meant taking a divided gospel to non-Western peoples. Overcoming this situation, in fact, was the main impulse behind the famous Edinburgh Missionary Conference of 1910.[9] A key commission at this conference was entitled ‘Co-operation and the Promotion of Unity’. The report of this commission lamented Christian divisions and stated that ‘for the achievement of the ultimate and highest end of all missionary work in . . . non-Christian lands of Christ’s one Church—real unity must be attained.’[10] This sentiment gave birth to the modern ecumenical movement—a movement of far-reaching significance in twentieth-century church history.However, as often happens, this movement produced ironic consequences. On the one hand, the original missionary impulse behind Edinburgh later became routinized and bureaucratized into the apparatus known as the World Council of Churches (WCC, f 1948)—a body which soon lost all zeal for evangelism. An op-ed in Christianity Today of 1965 perceptively noted, ‘a movement of Christian unity that began in evangelical transdenominational zeal to evangelize the world has resulted in a theological conglomerate in which evangelism is muffled and the evangel confused.’[11] Such lines of criticism can also be found among many mainline Protestant theologians, such as Paul Ramsey and Thomas Oden, who have criticized the WCC for substituting grandstanding, left-leaning political gestures for the work of serious ecumenism.

On the other hand, despite the original evangelical impulses of Edinburgh 1910, many evangelicals in the late twentieth century came to assume that ecumenism was something that only liberal Christians did; and, therefore, they should wash their hands of it.

Embarrassment over disunity

This is fair enough, but the abuse of the thing does not invalidate the proper use of a thing—only the abuse itself. Therefore, I am persuaded, that 500 years after the Reformation, evangelicals cannot simply yawn and walk away from Christ’s command that we all be one. The evangelical and the ecumenical priorities remain joined at the hip, as Christ himself testifies in the Gospel of John. They stand or fall together.[12]

However, it is fair to ask what one can possibly do. The divisions that started after 1517—as well as earlier and later ones—are not likely to be going away any time soon.

EVANGELICALS WHO CARE ABOUT THE GREAT COMMISSION SHOULD AT THE VERY LEAST MAKE EFFORTS TO BECOME MORE ZEALOUSLY EMBARRASSED AND SADDENED BY CHURCH DIVISIONS.

Here is a modest proposal: evangelicals who care about the Great Commission should at the very least make efforts to become more zealously embarrassed and saddened by church divisions. For if Christian unity is our Lord’s prayer, it seems that we have no option but to be embarrassed, indeed scandalized, by the actual situation of church divisions, past and present.Writing more generally about the religious purposes of embarrassment, the great Jewish thinker Abraham Joshua Heschel once wrote, ‘I am afraid of people who are never embarrassed at their own pettiness, envy, conceit, never embarrassed by the profanation of life.’ ‘Embarrassment is a response to the discovery that in living we . . . [have] frustrate[d] a wondrous expectation.’ In addition, Heschel wrote, ‘Embarrassment is the awareness of an incongruity between the challenges that we face and of our squandering the opportunity to meet them.’[13] In Christian terms, we have let down Christ; we have divided his body; we have frustrated his wondrous expectation of our unity. In short, we have stumbled, and this is embarrassing!

It is also sad. We should perhaps then be like Peter, remembering the Lord’s words after he had denied Jesus three times. As Matthew records, ‘And Peter remembered the saying of the Lord . . . . And he went out and wept bitterly’ (Matt 26:75). The maintenance of the divided body of Christ is tantamount to a denial of Christ’s own word.

Christ’s power in our weakness

Yet embarrassment and sadness should not lead to despair. Despair is not a valid option for Christians. For it is often in our very weakness that Christ’s power can shine forth all the more. This realization was important for none other than Martin Luther himself in formulating his well-known theology of the cross. For Luther, divine power is not revealed in the powers of this world, but rather in the weakness of the cross; for it was in his apparent defeat at the hands of evil that Jesus shows his divine power and the conquest of death and of all the powers of evil. Perhaps, too, in our very weakness, in the very things that should embarrass and sadden us, our Lord—500 years after the Reformation—can still manifest his power in our faults, and look on us with undeserved mercy to do his work, somehow, despite the lacerations that we have caused in his Bride, the church.

Toward these ends, may I conclude with a prayer for Christian unity found in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer:[14]

‘O God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ,

our only Savior, the Prince of Peace:

give us grace seriously to lay to heart

the great dangers we are in by our unhappy divisions.

Take away all hatred and prejudice,

and whatever else may hinder us

from godly union and concord;

that, as there is but one body and one Spirit,

one hope of our calling,

one Lord, one faith, one baptism,

one God and Father of us all,

so we may henceforth be all of one heart and of one soul,

united in one holy bond of peace, of faith and charity,

and may with one mind and one mouth glorify you;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.’

Endnotes- Editor’s Note: See Thomas Albert Howard and Mark A. Noll, ed.s, Protestantism after 500 Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). ↑

- Jaroslav Pelikan, The Riddle of Roman Catholicism (New York: Abingdon Press, 1949), 46. Cf. our usage of Pelikan in Howard and Noll, eds., Protestantism after 500 Years, 15-17. ↑

- Sermon of Stanley Hauerwas on October, 29, 2009 found at http://www.calledtocommunion.com/2009/10/stanley-hauerwas-on-reformation-sunday/. ↑

- Cited in Frank Furedi, On Tolerance (London: Continuum, 2011), 33. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Ron Anderson and Dave Miller, entitled ‘Effective Disciple-Making: Five Simple Truths for Contemporary Church Planters’, in this November 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis. ↑

- Emphasis added. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See Shusako Endo, Silence: A Novel, trans. William Johnston (New York: Picador Classis, 2016). ↑

- Carl E. Braaten, Principles of Lutheran Theology (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1983), 58. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Mary Ho, entitled ‘Global Leadership for Global Mission: How mission leaders can become world-class global leaders’, in November 2016 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2016-11/global-leadership-for-global-mission. ↑

- Quoted in David. A. Kerr and Kenneth R. Ross, eds., Edinburgh 2010: Mission Then and Now (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2010), 241. ↑

- Quoted in Harold H. Rowden, “Edinburgh 1910, Evangelicals and the Ecumenical Movement,” Vox Evangelica 5 (1967): 49-71. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Phill Butler, entitled ‘Is Our Collaboration for the Kingdom Effective? Evaluating Ministry Networks and Partnerships’, in January 2016 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-01/is-our-collaboration-for-the-kingdom-effective. ↑

- Abraham Joshua Heschel, Essential Writings, ed. Susannah Heschel (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 54-56. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church (New York: Church Publishing Inc, 1979). ↑

Thomas Albert (‘Tal’) Howard is Professor of Humanities and History and holds the Duesenberg Chair in Christian Ethics at Valparaiso University (Indiana, USA). He is the author of Remembering the Reformation: An Inquiry into the Meanings of Protestantism (Oxford, 2016) and editor (with Mark A. Noll) of Protestantism after 500 Years (Oxford, 2016).

Thomas Albert (‘Tal’) Howard is Professor of Humanities and History and holds the Duesenberg Chair in Christian Ethics at Valparaiso University (Indiana, USA). He is the author of Remembering the Reformation: An Inquiry into the Meanings of Protestantism (Oxford, 2016) and editor (with Mark A. Noll) of Protestantism after 500 Years (Oxford, 2016). Unlocking Theological Resource Sharing Between North and South - The need for missional theological education that values the whole church

Unlocking Theological Resource Sharing Between North and South - The need for missional theological education that values the whole churchKirsteen Kim

A key dilemma faced by theological educators is that, whereas most students are in the South, many of the resources are in the North. Recently, an African colleague gave me some insight into his situation in an email apologizing for not having time to contribute to a book series: ‘This morning I walked into a class on Soteriology and counted 104 students taking the course! Tomorrow morning I have another 50 in my Pentecostal Studies class!’

Imbalance between South and North

What a joy it was to have large numbers of students in South Korea and India in the 1980s and 1990s, and how hard it is currently to recruit for theology in Europe. Here in the North there are more opportunities for research and producing textbooks but there is a poverty of theological community, whereas in the South there is a paucity of learning resources and a shortage of qualified faculty.

HERE IN THE NORTH THERE ARE MORE OPPORTUNITIES FOR RESEARCH AND PRODUCING TEXTBOOKS BUT THERE IS A POVERTY OF THEOLOGICAL COMMUNITY.

When the Apostle Paul urged the Corinthians to participate in a collection for the believers in Jerusalem, who were facing famine, he justified it as ‘a question of a fair balance between your present abundance and their need, so that their abundance may be for your need, in order that there may be a fair balance.’ Today there is an imbalance between South and North in theological education that similarly needs addressing so that, in the body of Christ and in the kingdom of God, neither has too much or too little (2 Cor 8:13-15).Paul’s words above imply that the present state of affairs is not a permanent one. We can even expect a scenario in which the needs will be reversed. In fact we already see it changing:

- Although, throughout the North, the overwhelming majority of church leaders have theological education, sometimes to doctoral level, overall enrolment in theological education is declining, including in evangelical schools.

- In the South, many churches are led by people without the benefit of theological education and without access to it. However, although concrete data on theological education in the South is lacking, regional theological associations report rapid growth. Moreover, some faculty at institutions in the South now have higher levels of faculty qualifications to enable them to offer doctoral degrees.

Despite the financial constraints, there is much that can be done to address the current imbalance in theological education between North and South. I shall give some practical examples and suggestions of resource sharing below. However, in order for this to happen, we need the kind of theological education that encourages such sharing.

DESPITE THE FINANCIAL CONSTRAINTS, THERE IS MUCH THAT CAN BE DONE TO ADDRESS THE CURRENT IMBALANCE IN THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION BETWEEN NORTH AND SOUTH.

The Cape Town Commitment calls for theological education that is biblical and missional (CTC II F 4). It asserts that ‘theological education is intrinsically missional’ and it calls on theological educators to ‘ensure that it is intentionally missional’ (CTC II F 4A). Mindful of Christ’s commission to disciple all nations, missional theological education will serve the whole of global Christianity and not only the privileged few. Mindful of the love of God for all people, theological education will be done in a way that is respectful of local contexts and the giftedness of others.One of the reasons for the inadequate resource sharing is that theological education—both in the North and the South—is dominated by models developed to serve the institutional church of a largely homogenous community in a particular locality.

Along with the development of missional church, we need missional theological education. Becoming missional is not just a matter of adding in optional courses in ‘missiology’ or ‘global Christianity’; it requires a paradigm shift in the way the entire theological curriculum is taught. This change is happening:

- Biblical studies is recognizing the cultural and regional diversity of the early church.

- Systematic theology is taking account of the systems of thought in Asia, Africa, and indigenous peoples.

- Church history is becoming integrated with mission history, and recognizing the polycentric nature of Christian movements.

- Practical theology is focusing not only on local but also on global questions and on their interconnectedness.

THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION SUFFERS UNDER THE LEGACY OF COLONIAL RELATIONSHIPS OF DEPENDENCY AND UNDER CAPITALIST ASSUMPTIONS.

Another reason for lack of sharing is that theological education does not always take account of world Christianity, which is polycentric. Instead it suffers under the legacy of colonial relationships of dependency and under capitalist assumptions that value is represented by material wealth.In a post-colonial world, partnership[1] has become a key word to describe mutual respect and recognition of need on both sides. Partnership in theological education recognizes that learning is a two-way process and demands that, as the Kenyan theological John Mbiti once said, ‘we know one another theologically.’[2]

There are some great examples of sharing of both human resources and learning resources. It is only possible to refer to a selection of these.

At the human level, a missional theological education requires encounter with people from other contexts. The Langham Partnership facilitates the sharing of human resources—North to South and South to South—through theological exchange programs. Engaging with Christians from other parts of the world educates about world Christianity and builds the whole church. In a climate of market-driven competition between schools, such partnerships help to avoid Northern institutions undercutting theological provision in the South.

To bring equality in theological education, Christian agencies have to work against the dominance of the North in higher education globally, discourage the ‘brain drain’ from South to North, and find ways of capacity building in the South. The Oxford Centre for Mission Studies has a long history of facilitating students from the South to obtain doctoral degrees in the North while minimizing the cost and the time spent away from their families. The Center for Missiological Research at Fuller Theological Seminary and the Mission Theology in the Anglican Communion project facilitate sabbaticals for faculty from the South for research purposes.

Resource sharing can also take place through shared research. Probably the most significant example in mission studies was the Edinburgh 2010 project that prepared for the centenary of the 1910 World Missionary Conference. The project, which was funded by global church bodies and mission agencies across all the denominations, mandated the involvement of the whole of world Christianity. This was achieved by bringing together, under each of the nine study themes, groups and institutes from different regions.

So, for example, the report on Mission Spirituality and Authentic Discipleship was informed by researchers from CMS-UK, the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, the Akrofi-Christaller Institute in Ghana, the Instituto de Misionología at the Universidad Católica Boliviana in Cochabamba, and the Commission on World Mission and Evangelism of the World Council of Churches. The resulting report to the conference was a dialogue between all of these.

New online communications platforms allow for mediated learning and for many different modes of delivery of theological education. The webinar, for example, can generate a truly global audience and meaningful intercultural interaction. Northern institutions can share this software, and also their expertise, so that webinars and other global conversations can be initiated from and within the South. The provision of online education is dominated at present by Northern institutions and agencies, many of whom recruit from the South. However, partnership arrangements could offer students in different regions, including the North, the opportunity to take courses originating from the South.

The most acutely felt need in the South is for learning resources. Most academic works and textbooks are published in the North but are too expensive for students and even libraries to buy. Access to electronic resources may be similarly limited because these are controlled by the same publishing houses.

The Langham Partnership and SPCK have long been leading the effort to produce affordable literature for theological education produced by scholars in the South as well as the North. However, the growth and global spread of the internet has opened new possibilities for developing common learning resources. There are several projects to make theological resources available to students in the South and across global regions. The most extensive—with 650,000 items—is GlobeTheoLib. It was initiated by Globethics.net and the World Council of Churches to provide a common platform for existing digital resources and theological libraries with free access in multiple languages.

On a smaller scale, Regnum Books International produced the books of the Edinburgh 2010 project and then developed these into the Regnum Edinburgh Centenary Series of 35 volumes on mission and evangelism in world Christianity. Through the funding of church and mission agencies, and the generosity of Regnum, these are available for free download from the Regnum website as PDF files. Further funds have been raised to convert each volume into a more readable and searchable online form. This material not only allows sharing of mission theology and practice globally but also provides a database of world Christianity for further research.

On a smaller scale, Regnum Books International produced the books of the Edinburgh 2010 project and then developed these into the Regnum Edinburgh Centenary Series of 35 volumes on mission and evangelism in world Christianity. Through the funding of church and mission agencies, and the generosity of Regnum, these are available for free download from the Regnum website as PDF files. Further funds have been raised to convert each volume into a more readable and searchable online form. This material not only allows sharing of mission theology and practice globally but also provides a database of world Christianity for further research.Even the primary sources and archives needed to research Christianity in the South may be held in the North. Yale Divinity School Library, among others, is working to digitize mission archives, which will make them more readily accessible in the South. The Dictionary of African Christian Biography, led by African scholars and based at Boston University, aims to produce an electronic database to record the lives of those chiefly responsible for laying the foundations, shaping the character, and advancing the growth of Christian communities across Africa. There is a sister Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity.

The Regnum and Boston projects in particular not only share Northern resources with the South but also make Southern resources available globally, including in the North. This is another necessary part of correcting the imbalance in theological education. Some Northern-based academic journals—such as the leading mission studies journals—encourage articles from scholars in the South, whose work may not otherwise be known there. There are also now several book series that aim to represent world Christianity. However, it has to be said that many Northern theologians do not yet recognize their need of reading insights from the South. This is their loss, and convincing them of this is an important dimension of developing missional theological education.

Conclusion

The technologies are there to facilitate global theological resource sharing. There is a way but what is needed is a will. Resource sharing between North and South is not another means by which the former can help the latter ‘develop’ but a reciprocal activity with mutual benefits. The examples above show that it is missional theological education that values the whole church that is the key to unlocking theological resource sharing between North and South.

Further resources:

- Association of Theological Schools (ATS), 2015 State of the Industry Webinar. Available from http://www.ats.edu/resources/publications-and-presentations.

- S. Bevans, T. Chai, N. Jennings, K. Jørgensen and D. Werner (ed.s), Reflecting on and Equipping for Christian Mission, Regnum Edinburgh Centenary Series 27 (Oxford: Regnum Books,2015).

- Edinburgh 2010 Project, www.edinburgh2010.org.

- GlobeTheoLib, Global Digital Library on Theology and Ecumenism, http://www.globethics.net/gtl.

- Sebastian Kim and Kirsteen Kim, Christianity as a World Religion: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

- Lausanne Movement, ‘Effective Theological Education for World Evangelization’, Lausanne Occasional Paper No. 57 (2004). Available from https://www.lausanne.org/category/content/lop.

- Lausanne Movement, 2012 Consultation on Global Theological Education, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, USA, 29 May 2012 – 1 June 2012. Videos available at https://www.lausanne.org/tag/theological-education.

- Regnum Edinburgh Centenary Series. Downloadable from http://www.ocms.ac.uk/regnum/list.php?cat=3.

- D. Werner, D. Esterline, N. Kang and J. Raja (ed.s), Handbook of Theological Education in World Christianity: Theological Perspectives, Ecumenical Trends, Regional Surveys (Oxford: Regnum Books, 2010).

- Editor’s Note: See article by Phill Butler entitled, ‘Is Our Partnership for the Kingdom Effective? Evaluating Ministry Partnerships and Networks’ in January 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-01/is-our-collaboration-for-the-kingdom-effective. ↑

- J. Mbiti, ‘Theological Impotence and the Universality of the Church’, in G. H. Anderson and T. F. Stransky (ed.s), Third World Theologies (New York: Paulist, 1976), 17. ↑

In July of 2017 Kirsteen Kim was appointed as Professor of Theology and World Christianity in the School of Intercultural Studies, Fuller Theological Seminary, USA. She has served as a theological educator in the UK, South Korea and India. Her publications include Joining in with the Spirit: Connecting World Church and Local Mission (Bloomsbury). She is a member of the Lausanne Theology Working Group and edits Mission Studies, the journal of the International Association for Mission Studies.

In July of 2017 Kirsteen Kim was appointed as Professor of Theology and World Christianity in the School of Intercultural Studies, Fuller Theological Seminary, USA. She has served as a theological educator in the UK, South Korea and India. Her publications include Joining in with the Spirit: Connecting World Church and Local Mission (Bloomsbury). She is a member of the Lausanne Theology Working Group and edits Mission Studies, the journal of the International Association for Mission Studies. Connecting Across Generations for Global Mission - 5 Lessons from Lausanne's engagement with younger leaders

Connecting Across Generations for Global Mission - 5 Lessons from Lausanne's engagement with younger leadersLars Dahle, Nana Yaw Offei Awuku and Rudolf Kabutz

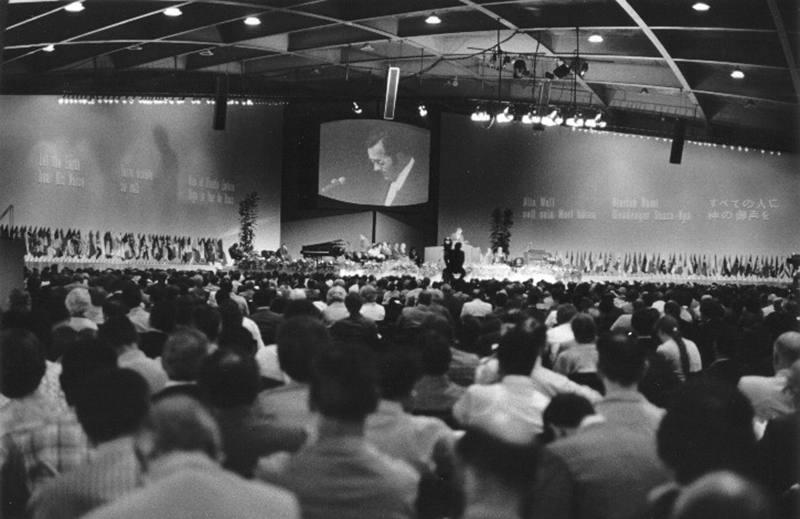

The Lausanne Movement has significantly impacted Christian mission for over 40 years. It exists to connect influencers and ideas for global mission—across issues, regions, and generations.

Connecting missional leaders across generations is both historically and strategically at the heart of the Lausanne Movement. This article provides a window into the unique story of Younger Leaders (YL) initiatives within the movement by listening to past and present leaders,[1] and outlines key lessons for the global church.[2]

It is highly appropriate to reflect on this fascinating story in view of the recent celebration of the first anniversary of the third YL gathering and the launch of the 10-year YL Generation initiative.

A growing emphasis on younger leaders

The intergenerational emphasis was included from the very beginning within the movement, with many YL present at Lausanne I in 1974. Ramez Atallah was appointed as the first ‘youth representative’ on the Continuation Committee, later joined on the permanent Lausanne Committee (LCWE) by Ajith Fernando and Brian Stiller. In practice, founder Billy Graham, first chair Jack Dain, first international director Gottfried Osei-Mensa, and leading theologian John Stott, were all modelling intentional mentorship in their many influential relationships with YL.

As Lausanne chair and CEO (1976 – 1991), Ford commissioned Stiller to undertake a global review process to prepare for decisions in the LCWE. A key feasibility study in this review process included the following essential observations: ‘Continuing world evangelization requires present leadership to encourage younger leaders to take their place. . . . For the Lausanne Movement to continue to influence world evangelization, it is essential that the younger leadership catch its spirit.’

This growing vision of intergenerational partnership in global mission was shaped by the ‘spirit of Lausanne’, representing a shared communal attitude and practice of prayer, study, partnership, hope, and humility.

Singapore (YLG) 1987: ‘A Conference of Younger Leaders’[3]

Inspired by the growing vision and informed by the review process, decisions were made in LCWE to arrange a global ‘Conference of Younger Leaders’ in Singapore in 1987. The key appointments included Brian Stiller as chair, Steve Hoke as director, and Ramez Atallah as programme coordinator, being part of a wider global planning team of ‘dynamic, opinionated, entrepreneur-type younger leaders’.[4]

When retelling the Singapore 1987 story, Atallah reflects on why this Lausanne conference became such a turning point in the lives and ministries of so many influential Christian leaders. He points out that the process was as important as the event: ‘I firmly believe that one of the main reasons the conference was a remarkable success was because of what God did in each one of us in the planning group. . . . To me it was proof that a well-chosen group of 300 younger leaders can impact the global church.’[5]

‘Passing the torch’ of leadership to the next generation[6] was a key concern at the first YLG in Singapore 1987, thus modelling the missional significance of intergenerational partnerships and friendships for the global church.

Malaysia (YLG) 2006: ‘Live and Lead like Jesus’[7]

Following Lausanne II in Manila in 1989, the Lausanne Movement went through a challenging decade. It survived due to the faithful service of leaders such as John Reid, Fergus Macdonald, and Paul Cedar.

Michael Oh (Lausanne CEO 2012 – present) describes the planning process for YLG 2006 as ‘the best, but not the easiest, team experience of my life’. Despite gaps in culture, calling, experience, gifting, and personality, a unique bonding emerged. He continues:

‘That experience taught me so much about the mission of the Lausanne Movement to connect. And it is not just a functional connection to do things together. As important as the doing of global mission is, it is the relational being together that really is a critical empowering dynamic to enable true, long-lasting doing.’

The programme focused on opportunities for—and barriers to—sharing the gospel, with plenaries, small group discussions with mentors, workshops, and regional meetings. As Doug Birdsall pointed out at the time, the whole gathering was forward-looking, seeking ‘to be faithful to a rich heritage of the past just as it [was] committed to responsible obedience with the challenges and opportunities of the future.’[9]Christ-like servant leadership across generations was a central theme at Malaysia 2006, thus modelling the missional significance of character and partnership to the global church.

Jakarta (YLG) 2016: ‘United in the Great Story’[10]

After Lausanne III in Cape Town in 2010, the global need for a third YLG became apparent. A Younger Leaders Planning Team was appointed, with Sarah Breuel as Chair and Ole-Magnus Olafsrud as Senior Coordinator.[11]

The continuity with previous YLGs was emphasized by Breuel:

‘Singapore 1987 deeply inspired us because of the stories we had heard of many of today’s global leaders who were there and how critical this event had been in their lives. Malaysia 2006 was also important, because we had read the feedback of how much the time in small groups sharing their life stories was the highlight for many; so we wanted to take a similar direction in this area.’

‘Connections were our highest value,’ Olafsrud points out. This became especially evident through the Connector App set up before the event and through the deep personal sharing of life stories during the event. He continues, ‘This brought us deep with one another and with the Lord—and United in the Great Story.’

Learning from the biblical story and from one another’s stories were key themes at Jakarta 2016, thus modelling a forward-looking intergenerational missional learning community to the global church.[12]

YLGen: A Global Intergenerational Commitment (2016 – 2026)[13]A new global initiative was launched in 2016 to steward faithfully the connections and fruits from YLG 2016 for greater missional impact. It is a ten-year commitment to walk alongside YL. The intention is to connect them more intentionally to Lausanne issue networks, regions, resources, and mentors, as well as to one another through various interest groups.

Olafsrud makes a similar observation: ‘Both YLG 2016 and YLGen show—even stronger than at YLG 2006—the hunger for and potential of mutually being equipped as leaders through relationships and partnerships across the generations.’

This recent major initiative is going far beyond previous Lausanne YL initiatives in its scope and depth. It represents a unique long-term strategic investment in the YLG 2016 community and beyond, in order to equip emerging generations of evangelical influencers to engage future missional contexts, tasks, and issues.

YLGen models intergenerational missional discipleship and partnership to the global church by focusing simultaneously on a character goal (‘grow to live and lead like Jesus’), a missional goal (‘so that the world may know Christ’), and a friendship goal (‘inspire connections marked by the spirit of Lausanne’).

Five key lessons for the global church

It has often been said that the fruit of the Lausanne Movement grows best on other peoples’ trees and that its most effective role is serving as a catalyst.

We sincerely hope that these five key lessons from the distinctive story of the Lausanne YL initiatives may inspire the global church:

- Shared personal commitments to holistic mission across generations lead to global Christian friendships and gospel partnerships.

- Shared evangelical convictions across generations, as expressed in The Lausanne Covenant and The Cape Town Commitment, lead to shared global missional reflections and strategic ministry collaborations.

- Mutual trust may be developed through intentional relational processes, with more experienced leaders mentoring younger leaders to take on missional tasks according to their personal callings and gifts, and with younger leaders inspiring experienced leaders to embrace thinking and acting from new paradigms.

- Innovative space is created for younger leaders to develop personal character and skills with biblical integrity for transformative ministry in complex, rapidly changing future contexts.

- These intergenerational relationships are characterized by the ‘spirit of Lausanne’, with a shared focus on prayer, study, partnership, hope, and humility.

Endnotes:

- In preparation for this article, the authors have been privileged to receive personal stories and reflections from many past and present Lausanne leaders. We also acknowledge with gratitude the assistance from Director Paul Ericksen at BGC Archives and Museum, Wheaton College, who provided key material from ‘Records of the LCWE: Collection 46’. ↑

- The stories and the reflections will be expanded in a forthcoming in-depth article by Lars Dahle. ↑

- See https://www.lausanne.org/gatherings/ylg/younger-leaders-gathering-1987. ↑

- Ramez Atallah, ‘Continuing the Vision from Lausanne 1974’, in L. Dahle, M. S. Dahle and K. Jørgensen (eds.) The Lausanne Movement: A Range of Perspectives (Oxford: Regnum Books, 2014), 77. ↑

- Ibid., 78. ↑

- Chris Wright observes that John Stott personally modelled ‘the godly, wise, and humble handing over of leadership’ to younger leaders, both at All Souls Church and in Langham Ministries. ↑

- See https://www.lausanne.org/gatherings/ylg/younger-leaders-gathering-2006-2. ↑

- Leighton Ford coined this phrase; see https://www.leightonfordministries.org/leadership/. ↑

- See https://www.lausanneworldpulse.com/leadershipmemo/299/04-2006. ↑

- See https://www.lausanne.org/gatherings/ylg/younger-leaders-gathering-2016. ↑

- See Sarah Breuel and Dave Benson, ‘Six Leadership Lessons from YLG2016’, Lausanne Global Analysis, Nov 2016, vol. 5:6 (https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2016-11/six-leadership-lessons-from-ylg2016). ↑

- See Nana Yaw Offei Awuku, ‘Engaging an Emerging Generation of Global Mission Leaders: Embracing the Challenge of Partnerships’, Lausanne Global Analysis, Nov. 2016, vol. 5:6 (https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2016-11/engaging-an-emerging-generation-of-global-mission-leaders). ↑

- See https://www.lausanne.org/ylgen. ↑

- CTC, Foreword, see https://www.lausanne.org/content/ctc/ctcommitment#foreword and L. Dahle, ‘Mission in 3D: A Key Lausanne III Theme’, in L. Dahle, M. S. Dahle and K. Jørgensen (eds.) The Lausanne Movement: A Range of Perspectives (Oxford: Regnum Books, 2014), 265-79. ↑

Lars Dahle is Associate Professor in Systematic Theology (with specific emphasis on Christian Apologetics) at Gimlekollen School of Journalism and Apologetics, NLA University College (Kristiansand, Norway); CEO of Damaris Norge (an extended activity of Gimlekollen); and Founding Editor of the journal Theofilos. He is co-editor of and contributor to The Lausanne Movement: A Range of Perspectives (Oxford: Regnum 2014). He co-leads with Rudolf Kabutz as Lausanne Catalyst for Media Engagement.

Lars Dahle is Associate Professor in Systematic Theology (with specific emphasis on Christian Apologetics) at Gimlekollen School of Journalism and Apologetics, NLA University College (Kristiansand, Norway); CEO of Damaris Norge (an extended activity of Gimlekollen); and Founding Editor of the journal Theofilos. He is co-editor of and contributor to The Lausanne Movement: A Range of Perspectives (Oxford: Regnum 2014). He co-leads with Rudolf Kabutz as Lausanne Catalyst for Media Engagement. Nana Yaw Offei Awuku has been on staff with Scripture Union Ghana for over 20 years and currently serves on the Senior Management Team as the Director for Field Ministries. Beginning in January, 2018, he will become the Lausanne Global Associate Director for Generations, directing the Younger Leaders Generation (YLGen) initiative. He was previously the Lausanne Regional Director for English, Portuguese, and Spanish-speaking Africa (EPSA).

Nana Yaw Offei Awuku has been on staff with Scripture Union Ghana for over 20 years and currently serves on the Senior Management Team as the Director for Field Ministries. Beginning in January, 2018, he will become the Lausanne Global Associate Director for Generations, directing the Younger Leaders Generation (YLGen) initiative. He was previously the Lausanne Regional Director for English, Portuguese, and Spanish-speaking Africa (EPSA). Rudolf Kabutz serves with TWR in South Africa as a future media strategist and project coordinator, focusing on using new social media initiatives to supplement broadcasting media for equipping leaders in Africa. Holding master’s degrees in mathematics as well as strategic foresight, he co-leads with Lars Dahle as Lausanne Catalyst for Media Engagement.

Rudolf Kabutz serves with TWR in South Africa as a future media strategist and project coordinator, focusing on using new social media initiatives to supplement broadcasting media for equipping leaders in Africa. Holding master’s degrees in mathematics as well as strategic foresight, he co-leads with Lars Dahle as Lausanne Catalyst for Media Engagement. 5 Truths for Church Planting Today - How to be effective in disciple-making in the twenty-first century

5 Truths for Church Planting Today - How to be effective in disciple-making in the twenty-first centuryDavid Miller and Ron Anderson

With his Afro haircut and sculpted beard, he looked more like a pop musician than a church planter. Actually, he was both. He and some buddies were reaching youth in the impoverished favelas of Sao Paulo, Brazil, by offering free music lessons. The young man had come to our church planting consultation to see what he could learn.

As typically happens in these meetings, the young Brazilian church planter taught us some important lessons.

Church planting collective knowledge

Data from written surveys and roundtable discussions reveal a universal interest in planting healthy churches, as well as challenges common to church planters the world over.[1] Consultations have produced a rich blend of experience, achievement, burdens, and aspirations. After much sifting and reflection, we condensed this collective knowledge into Five Simple Truths about planting churches in the early twenty-first century, hoping to spark yet more discussion on the issues:

1. The most urgent challenge we face is to make disciples of the next generation.

Church planters across Latin America and Europe have expressed concern about how to make disciples of the next generation. Today’s youth, particularly those in urban, postmodern cultures are not keen on ‘organized religion’. Evangelical churches in these communities are attracting few young people. In fact, more members of the next generation are exiting, rather than entering, churches.

‘YOU HAVE TO TELL THESE KIDS UP-FRONT THAT YOU ARE A CHRISTIAN AND YOU WANT THEM TO KNOW THE LORD.’

That is the bad news. The good news is that these same young people are more interested than ever in knowing Jesus, and they become his enthusiastic followers if introduced to the gospel. They also prove marvelously effective in making disciples of other postmodern urban youth.The young pop musician-church planter in Sao Paulo told us, ‘We tell the kids up front that, while they learn guitar or keyboards, they will also learn about Jesus. They don’t get in the program if they don’t agree to that.’

Eyebrows shot up at this comment. His tactic went against principles taught in missions classes. One must first build relationships with a target group, conventional wisdom says, investing months or even years before ‘earning the right’ to introduce people to the gospel.

‘That doesn’t work for us’, the young man said. ‘You have to tell these kids up-front that you are a Christian and you want them to know the Lord. If you wait to bring it up later, they think you’ve conned them and they drop out’. He then explained that favelakids are actually more eager to sign up for music classes when Jesus is part of the curriculum.

2. We must learn and follow basic biblical ecclesiology.

The New Testament reveals how the early church was constituted to carry out the Great Commission. Despite the triple threats of social ostracism, official persecution and internal heresy, the first generations of Jesus’ followers made faithful disciples of their countrymen at a rate unparalleled in history. We believe that a careful application of New Testament ecclesiology today will produce the same astonishing results.

Alan Hirsch cogently argues this conviction in his book, The Forgotten Ways: Reactivating the Missional Church. Hirsch believes we can do church in our day and age like the apostles did in the first century. He then offers five essential marks of biblical ecclesiology to help us recover the genius of the apostolic church:

In Lausanne church planting consultations, we ask participants, ‘Which of these five traits of the New Testament church is it most urgent for your national church to recover?’

Responses vary remarkably, depending on different historical and social contexts:

- In Central America (El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua), leaders feel strongly that the church’s most urgent challenge is to make disciples.

- Brazilians, on the other hand, consistently state that they must return Christ to the center of the church.

- In the Balkans, leaders confess that allowing every Christian to take his or her rightful place in the priesthood of believers is a huge need.

- Spanish leaders identify a lack of missional vision as their number one challenge.

In a survey we conducted in Spain, 150 youth ministers shared their ideas on how to reach the next generation for Jesus. They voiced a strong opinion that we need new expressions of church that emphasize everyone taking part in the ministry. They pointed out that young people tend to get bored and leave groups when they are no longer valued as individuals and given opportunity to contribute.

WE NEED NEW EXPRESSIONS OF CHURCH THAT EMPHASIZE EVERYONE TAKING PART IN THE MINISTRY.

In Alcala de Henares, Spain, a group of eight Christians was frustrated because they were not actively engaged in the mission of God in their city. So, with great care to maintain peace with their respective congregations, they took it upon themselves to rent an empty storefront on the ground floor of an apartment complex in a heavily populated, low-income area of the city. The group initiated activities that employed each person’s unique gifts, such as a scrapbook club, English conversation classes, and aerobic workouts for Muslim women. Before long, this group was welcoming 50 non-Christians each week into one or more of their Bible-based activities.The wife of a church elder expressed her satisfaction with tears of joy: ‘No one has ever given me an opportunity like this before, to express my faith in ways that go with my motivations and gifting.’ Eventually one of the group’s home churches took notice and applauded the effort. At the time of writing, this congregation is considering how to release more of its members to the local mission field, using this pilot project as its model.

4. Christians must collaborate with each other to impact the world.

Jesus in his heartfelt conversation with the Father recorded in John 17 gave us a key to reaching his generation, this generation and every succeeding generation: ‘I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me.’ (John 17:20b-21).

Many believers today do not understand why there are so many ‘silos’ in the Christian world. Worse yet, they are very confused about why people in these silos do not work together, or even get along with one another.[2]

WHEN CHALLENGED TO PINPOINT WHAT WAS KEEPING THEM FROM HAVING GREATER IMPACT, THE RESPONSE WAS, ‘IT IS BECAUSE WE ARE NOT WORKING TOGETHER AS ONE BODY.’

In 2016, our network held a one-day consultation in Croatia with 25 denominational and mission leaders from across the country. Apprehension about the meeting prevailed, given historic rifts between denominations. In fact, when asked what would be a good outcome of the meeting, one leader answered, ‘Anything short of drawing blood.’The meeting went very well, with no casualties to report. However, many were astonished to hear from a local statistician that Croatia has only 178 churches in a population of four million. The rate of growth is five new churches per year.

When challenged to pinpoint what was keeping them from having greater impact, the response was, ‘It is because we are not working together as one body.’ This discovery helped them break the silo trend and build personal relationships with one another. They went on to form a national church-planting platform with a shared vision to reach Croatia.

Over the past decade, scores of grassroots church-planting movements in Europe have broken out of the silos that separate the Body of Christ. We have identified common elements in these collaborative networks that lead to success:

5 Networks build unity in the Body of Christ.

Lausanne is teaching us not to confuse the globalization of Christianity with unity in the Body of Christ. The astonishing growth of world Christianity in this generation is occurring in many diverse cultures and draws from divergent theological traditions. The ‘northern church’ in Europe and North America operates in a world fundamentally different from the ‘global South’, where indigenous churches are thriving. Wesley Granberg-Michaelson writes,

The theological gulf between these two worlds has widened even as Christianity’s center of gravity has continued its journey toward the global South. . . . In my judgment, the gulf between these two worlds now constitutes the most pressing challenge to the unity of the church in the twenty-first century. . . . This underscores the urgent need for new networks of relationships to be built. These networks need to be intentionally created in ways that cross the divisions of geography, theology, institutions and generations. Hopefully, such networks could multiply in diverse, growing ways.[3]

NETWORKS NEED TO BE INTENTIONALLY CREATED IN WAYS THAT CROSS THE DIVISIONS OF GEOGRAPHY, THEOLOGY, INSTITUTIONS AND GENERATIONS.

Church-planting networks are one class among many collaborative movements coalescing around the Great Commission. Some of these networks are informal and loosely connected, others have been intentionally organized and generously funded. However, whatever their class, it seems these networks are an answer to Jesus’ prayer: ‘That all of them may be one . . . so that the world may believe’ (John 17:21).‘That the world may believe’ should be the goal of every church planter. Granted some new churches today are launched to ‘plant the flag’ of a certain denomination in heretofore unclaimed territory, or to accommodate a demographic group that no longer feels comfortable in its parent congregation. However, Jesus has a different purpose for the church he is building.

The church came into being as Jesus’ disciples multiplied. It continues to exist to make more disciples of Jesus. This is its primary purpose. ‘Mission was not made for the church; the church was made for mission—God’s mission’, British theologian Chris Wright reminds us.[4]

So if church planting is to be effective in the twenty-first century, church planters must obey Jesus’ first century mandate to ‘make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you’ (Matt 28:19-20a).

This, we conclude, is the simplest truth of all about church planting.

Endnotes:

- Editor’s Note: See article by Kent Parks entitled ‘Finishing the Remaining 29% of World Evangelization’, in May 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-05/finishing-the-remaining-29-of-world-evangelization. See also article by Stephan Bauman entitled ‘What We Call the Edge, God Calls the Center’, in July 2015 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2015-07/what-we-call-the-edge-god-calls-the-center. ↑

- Editor’s Note: See article by Thomas Albert Howard, entitled ‘The 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation: a call to Christian Unity for the sake of the Great Commission’, in this November 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis. ↑

- Wesley Granberg-Michaelson, From Times Square to Timbuktu: The Post-Christian West Meets the Non-Western Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013), 19-20, 70. ↑

- Christopher J. H. Wright, The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2006), 62. ↑

David Miller and his wife Barbara have served since 1980 in Bolivia as itinerant evangelists and Bible teachers among indigenous Andean peoples. A trained journalist, Dave later worked as managing editor of Compass Direct News, reporting on global persecution of Christians. He served as Regional Coordinator for Global Missions of the Church of God, before assuming coordination of the Lausanne Latin America Church Planting Network in 2015. He has authored The Lord of Bellavista: The Dramatic Story of a Prison Transformed.

David Miller and his wife Barbara have served since 1980 in Bolivia as itinerant evangelists and Bible teachers among indigenous Andean peoples. A trained journalist, Dave later worked as managing editor of Compass Direct News, reporting on global persecution of Christians. He served as Regional Coordinator for Global Missions of the Church of God, before assuming coordination of the Lausanne Latin America Church Planting Network in 2015. He has authored The Lord of Bellavista: The Dramatic Story of a Prison Transformed. Ron Anderson is the Catalyst for the Lausanne Movement Church Planting Issue Network, and the Coordinator for the Spain National Church Planting Process called La Plaza del Plantador.com. Ron was born in Guatemala where his parents served among the Maya Quiche people. He and his wife Brenda reside in Madrid, Spain. For the past 39 years they have been with the European Christian Mission International, which Ron serves currently as a church planting consultant.

Ron Anderson is the Catalyst for the Lausanne Movement Church Planting Issue Network, and the Coordinator for the Spain National Church Planting Process called La Plaza del Plantador.com. Ron was born in Guatemala where his parents served among the Maya Quiche people. He and his wife Brenda reside in Madrid, Spain. For the past 39 years they have been with the European Christian Mission International, which Ron serves currently as a church planting consultant. Praying Purposefully Together for the World - The gift of the new Operation World app to the global church

Praying Purposefully Together for the World - The gift of the new Operation World app to the global churchJason Mandryk

We have more access to information today than ever before, but it seems harder than ever to discern the truth of what is happening in our big, wide world. Whether it is in relation to countries such as Syria, Venezuela, and North Korea or Islamist extremist groups such as ISIS, Boko Haram, and the Taliban (and so much more), it is a struggle to keep up with the constant swirl of breaking news and the complexity of world affairs.

Three dynamics work powerfully against the Christian engaging purposefully with the world through intercession:

- The ubiquitous nature of digital media: We can feel overwhelmed by a relentless 24/7 cycle of news and information.

- The politicized nature of the main media sources: We can feel locked into imposed narratives that communicate all news through specific biases.

- The sensationalization of mainstream news: We can fall into the trap of believing that airtime equals importance.

It is a full-time job just filtering through noise, parsing the agendas, and finding out about the world’s more neglected areas and issues.

It is a full-time job just filtering through noise, parsing the agendas, and finding out about the world’s more neglected areas and issues.That is why we feel that the recently released Operation World app is a useful tool for believers who care about our world and the people in it. Here are the reasons:

Our dream is to see people praying together for the nations, whether they are in a London suburb, the Maasai Mara, or a Manila slum. We are pleased that anyone with an Android or Apple internet-enabled device, anywhere, can use the app for free.[1] Once downloaded, you can use the app offline. We hope it will be a useful source of prayer material for people and places where there is not much available, and we hope to be able to see the content translated into many languages.

Every day there is just one prayer point for one nation or region. The last full edition of Operation World ran to over 1,000 pages—an intimidating prospect for most readers. You will get a notification (if you want) at your choice of time to remind you to pray. The highlighted prayer point only requires a couple of minutes of your attention, but there is much more content available in the app. You might choose to pray for several points or several countries.

When you pray for the highlighted point of the day (and the rest of the content), you are joining with many thousands of others, around the world, praying for the same thing. There is something powerful about knowing that the issue you are lifting up to God is being covered in prayer from around the globe; the app lets you see how many others have prayed for that country. You also have the ability to share the prayer point with others, as well as linking to further Operation World resources.

For over 50 years, Operation World has researched every country, and built connections in each of them, so that we can mobilize the body of Christ to pray for what matters most. What we report has been vetted not just by our own team, but by our contacts all around the world—missionaries, national church leaders, and other researchers.

To quote from Operation World’s introduction: ‘We do not merely pray about the many points featured herein, we pray toward something, and that something is magnificent—the fulfillment of the Father’s purposes and His Kingdom come.’ Operation World does not treat prayer merely as a bandage to help us cover over the cuts and scrapes of the issues that afflict us day-by-day. It sees intercession as the means to unleash the inestimable power of God into our broken world, bringing redemption, reconciliation, and healing.

Endnote:

1. All a person needs to do to find the app is to search for ‘Operation World’ in the app sre of their device. ↑

Jason is a Canadian who has lived most of his adult life in England, in Singapore, on a ship, in a tent, or in a castle. He has worked with Operation World in various capacities for nearly 20 years. His passion is to see good research and information mobilize prayer and mission around the world. Jason (and Operation World) is currently based on the campus of All Nations Christian College near London, England.

Jason is a Canadian who has lived most of his adult life in England, in Singapore, on a ship, in a tent, or in a castle. He has worked with Operation World in various capacities for nearly 20 years. His passion is to see good research and information mobilize prayer and mission around the world. Jason (and Operation World) is currently based on the campus of All Nations Christian College near London, England.---

Lausanne Global Analysis seeks to deliver strategic and credible information and insight from an international network of evangelical analysts to equip influencers of global mission. Browse all the past issues at lausanne.org/lga. The publication of the LGA is overseen by its Editorial Advisory Board. Articles represent a diversity of viewpoints within the bounds of our foundational documents. The views and opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the personal viewpoints of Lausanne Movement leaders or networks. Inquiries regarding the Lausanne Global Analysis may be addressed to analysis@lausanne.org.

-------

No comments:

Post a Comment