Traditional Christian Treatment of the Sick

whatsoever your sickness is, know you certainly, that it is God's visitation.

Book of Common Prayer, Order for the Visitation of the Sick

Traditional Christian doctrine held that illness was caused by sin. This belief was exactly in line with the gospels1 and was specifically confirmed by the Lateran Council in 1215. So it was that for centuries the sick and dying could safely be shunned and ignored. They must have deserved their condition, and attempts to help them were attempts to defy God's will. Monstrous human births were caused by the Devil having corrupted infants' souls, even before birth.

The belief was universal in Christianity, and carried over from Catholicism into Protestant sects at the Reformation. Here are a few examples from Martin Luther:

The belief was universal in Christianity, and carried over from Catholicism into Protestant sects at the Reformation. Here are a few examples from Martin Luther:

A large number of deaf, crippled and blind people are afflicted solely through the malice of the demon. And one must in no wise doubt that plagues, fevers and every sort of evil come from him.

and it was not only physical problems, mental problems were also attributable to Satan.

As for the demented, I hold it certain that all beings deprived of reason are thus afflicted only by the Devil.

and anyone who doubted demonic causes for illness were ridiculed (and where possible tried as heretics)

Idiots, the lame, the blind, the dumb, are men in whom the devils have established themselves: and all the physicians who heal these infirmities, as though they proceeded from natural causes, are ignorant blockheads....

Since disease-causing demons were God's punishment for sin, it was clearly a pious duty to accept that punishment. To minimise it or seek to avoid it would be further sin. This attitude led to a form of fatalism still widespread in the East and once common in Western Christendom too. If God wants a person to suffer or die, it is plainly blasphemous for that person to try to avoid their fate. Since the victims of plague were destined to die by God's decree, the disease could not really be contagious in any conventional sense, and there was no point in taking precautions against catching it. Many thousands of devout Christians thus suffered avoidable death and suffering. For example, during the Black Death in Britain in 1665, pious Christians declined to take precautions for the protection of their families, claiming that they did not wish to pervert God's will. As Daniel Defoe noted, places where this fatalistic attitude was common suffered significantly higher mortality rates than elsewhere. Well into the twentieth century, devout Christians relied on Psalm 91, which they said clearly confirmed that God would protect them from pestilence and other evils. The devout were held to be immune from epidemics, whatever the evidence might be. To be inoculated against disease was to doubt God's word, and therefore plainly sinful. So it was that many of the devout, and their trusting children, died unnecessarily in epidemics following the advice, or the orders, of their religious leaders.

Lepers were treated as God required in the Old Testament:

Lepers were treated as God required in the Old Testament:

He is a leprous man, he is unclean: the priest shall pronounce him utterly unclean; his plague is in his head. And the leper in whom the plague is, his clothes shall be rent, and his head bare, and he shall put a covering upon his upper lip, and shall cry, Unclean, unclean. (Leviticus 13:44-45)

God had condemned lepers to a living death, so Christians behaved accordingly. A ceremony was performed for the living dead parallel to that for the fully dead. When someone was thought to have contracted the disease, a neighbour would denounce the unfortunate person to the Church. An investigation would then be undertaken on behalf of the Church, often without medical assistance. If leprosy was established the parish priest would perform the "Office for the Seclusion of a Leper". He would go to the afflicted person's house, sprinkle the person with holy water, and offer him or her the chance to make confession for the last time. The afflicted person was then taken to the local Church where he or she was made to adopt a pose "in the manner of a dead man" before the altar, beneath trestles covered by black cloth. The idea was that the leper should resemble a body in a coffin. During the service, lepers were informed that their disease was God's punishment for sin, and sometimes, paradoxically, that this was a special divine favour. According to the ritual used at Vienna, the priest would say:

"My friend, it pleaseth Our Lord that thou shouldst be infected with this malady, and thou hast great grace at the hands of Our Lord that he desireth to punish thee for thy iniquities in this world"2.

After a ceremony the leper was dragged backwards or otherwise escorted out of the church. Earth was cast at his or her feet, as into a new grave, while the priest said

"Be thou dead to the world, but alive again unto God". The person was then admonished never to enter a church or other public place again, and was banished from the community. Lepers were dead not only spiritually and socially but also legally. They could not inherit property. At the Council of Westminster in 1200 they were forbidden to make wills or appear in court. The Church taught that the exterior physical body reflected the interior soul, so anyone with such a dreadful disease must have been excessively sinful. Leprosy was believed either to be a venereal disease or to be caused by lustful thoughts. Either way, leprosy was the visible sign of a soul corroded by the vitriol of sexual sin

Since lepers were by definition given to sin, and excluded from the community of good Christians, they provided convenient scapegoats. By marginalising them, Christendom made them into targets for unwholesome fantasies. Like all other minority groups they were accused of unlikely crimes. In 1321, for example, they were accused of poisoning wells in France. Lepers in Périgueux were rounded up and tortured until they confessed their guilt, and were then burned at the stake. The confessions prompted a terror similar to that more usually generated by Jews and witches. A story grew that a huge network of lepers, funded by the Muslims and aided by the Jews, had planned to poison all water supplies in the land. Forged letters turned up confirming the foul plot. King Philip V ordered the arrest of all lepers in France. Those who failed to confess were to be tortured. Those who did confess were to be burned alive, their goods being forfeit to the King. No records were kept of how many lepers died as a result3.

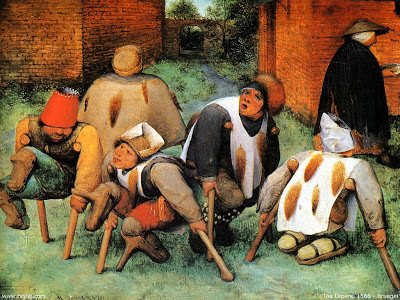

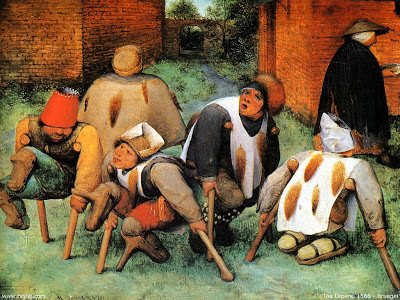

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Cripples (aka The Beggars), 1568 Universal Social Services are modern secular concepts, initially unknown to (and later opposed by) traditional Christian Churches

No Christian thought to try to find a cure for leprosy. It would be presumptuous to do that. For the holiest Christians like the Blessed Angela of Foligno, the nearest one could get to being useful was to drink from the suppurating sores of a leper.

No Christian thought to try to find a cure for leprosy. It would be presumptuous to do that. For the holiest Christians like the Blessed Angela of Foligno, the nearest one could get to being useful was to drink from the suppurating sores of a leper.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Cripples (aka The Beggars), 1568 Universal Social Services are modern secular concepts, initially unknown to (and later opposed by) traditional Christian Churches

Equating sin with illness is now widely considered absurd, though it is has been confirmed even by liberal denominations even in recent times. A report of the Anglican Church from the Lambeth Conference in 1958 confirmed the principle while shifting ground to avoid the traditional implications, so that the blame did not need to be pinned on any individual: "It is cruel and false to brand every sufferer as a sinner: much suffering and sickness is due to the sin either of other persons or of society in general". Since then the whole subject has become an embarrassment, except to a few sects that continue to hold to the traditional teaching. Mainstream clergymen go to extreme lengths to pretend that the biblical passages that confirm the link between sin and illness do not exist, or else mean something quite different. It is left to fringe Christians to uphold the traditional line and use exorcism to cast out sin and so cure diseases.

Demons used to be common and visible

Saint Francis of Assisi, An Exorcist of Demons

Demons used to be common and visible

Saint Francis of Assisi, An Exorcist of Demons

Saint Francis Borgia performing an exorcism, detail of a painting by Francisco Goya

Not so long ago Christians accepted the views of St Augustine that deaf mutes were debarred from the faith4. Like Augustine, they cited St Paul's assertion that "faith cometh by hearing" (Romans 10:17). The deaf were thus incapable of becoming Christians. For centuries they were marginalised, rejected and persecuted by all right-thinking Christians. The Church would not allow them to marry, nor to inherit. The deaf were not the only ones persecuted in this way — so were those with other disabilities, since disabilities were also evidence of God's unfavourable judgement. As late as the 1970s Roman Catholic priests were protesting publicly about Communion being given to disabled children.

Another idea propounded by the Church, and explained in Malleus Maleficarum5, was that God allowed demons to steal children and substitute subhuman infants, called changelings, in their place. This was likely to happen to children before they had been baptised, or before their mother had been churched. Such stories were used to encourage baptism and churching, and also to explain the existence of weak and sickly children. Sometimes children had withered limbs, or were deaf, blind, mentally impaired or crippled. Roman Catholics and Protestants alike imagined that these handicapped children — these changelings — were not human beings at all. Martin Luther, for example, advised that they be drowned. They were he said only lumps of flesh lacking a soul6. He could vauch for their existence from his personal experience: "I myself saw and touched at Dessay, a child of this sort, which had no human parents, but had proceeded from the Devil. He was twelve years old, and, in outward form, exactly resembled ordinary children". The Devil often exchanged sickly imps in place of healthy children. As Luther pointed out "The Devil, too, sometimes steals human children; it is not infrequent for him to carry away infants within the first six weeks after birth, and to substitute in their place imps...". Of course, murdering Satan's imps did not constitute murder. Luther's view was not an isolated exception. Walter Bachmann, who made a study of Christian attitudes to changelings, summed up the position as follows:

Since Christian shrines healed worthy Christians of their sins and illnesses, it followed that if no healing was forthcoming, then the sufferer cannot be a worthy Christian. Countless incurable children were therefore left to perish if no saint saw fit to heal them - since by definition such children cannot have been of value to God. Others survived by being adopted into less religiously rigorous families. In the thirteenth century, Margaret of Citta-Di-Castello, also known Margaret of Metola, was abandoned by her rich Christian parents when a cure for her blindness was not granted at a shrine. She was raised by a poor family, even though she was blind, dwarfed, hunchbacked and lame, and survived to become a notable visionary in the Catholic Church, though not a saint, presumably because of her physical deformities (which traditionally are not permitted in holy places).

Since Christian shrines healed worthy Christians of their sins and illnesses, it followed that if no healing was forthcoming, then the sufferer cannot be a worthy Christian. Countless incurable children were therefore left to perish if no saint saw fit to heal them - since by definition such children cannot have been of value to God. Others survived by being adopted into less religiously rigorous families. In the thirteenth century, Margaret of Citta-Di-Castello, also known Margaret of Metola, was abandoned by her rich Christian parents when a cure for her blindness was not granted at a shrine. She was raised by a poor family, even though she was blind, dwarfed, hunchbacked and lame, and survived to become a notable visionary in the Catholic Church, though not a saint, presumably because of her physical deformities (which traditionally are not permitted in holy places).

The bible is clear that deformities render a person unfit to be a Jewish priest, and the Church interpreted the relevant passages as referring also to Christian priests:

Hubert Ahaus, "Holy Orders." The Catholic Encyclopedia.

Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911.

The first requisite for lawful ordination is a Divine vocation; by which is understood the action of God, whereby He selects some to be His special ministers, endowing them with the spiritual, mental, moral, and physical qualities required for the fitting discharge of their order and inspiring them with a sincere desire to enter the ecclesiastical state for God's honor and their own sanctification. The reality of this Divine call is manifested in general by sanctity of life, right faith, knowledge corresponding to the proper exercise of the order to which one is raised, absence of physical defects, the age required by the canons ...

Some diseases, handicaps and injuries were sufficient to prevent people being allowed in Christian congregations at all. For example, genital injuries debarred men from attending church: "No one who is emasculated or has his male organ cut off shall enter the assembly of the LORD." (Deuteronomy 23:1). Other examples we have already seen include Deafness being a bar to being a Christian, and lepers who were not permitted to enter churches after a priest has read the service for the dead for them (on the discovery of their disease, not their death). In all cases the justification for exclusion was biblical.

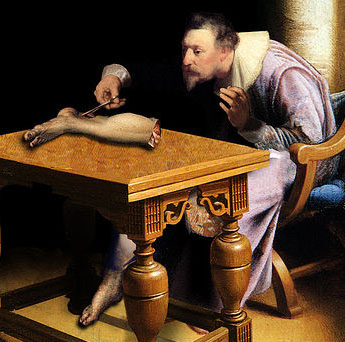

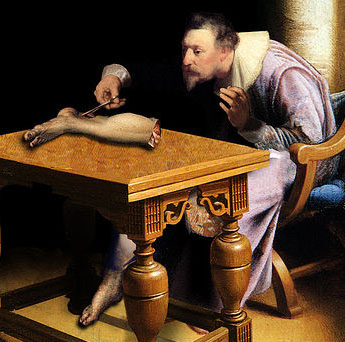

"Philip Verheyen dissecting his amputated limb", detail, Anonymous artist, c. 1715-1730.

Philip Verheyen had been a theology student destined for the priesthood, until his lower leg had to be amputated in 1675, debarring him from his vocation. (He kept his severed leg and subsequently became a famous anatomist and surgeon)

Mental infirmity, like physical infirmity, was a punishment from God. An interesting question for theologians was the degree of mental infirmity required to render a person subhuman. This was important because sub-humans were mere animals with no human souls. Without a soul they were not entitled to the privileges of humanity. They could not benefit from baptism nor from legal privileges. Like the excommunicated and outlaws, they were non-persons. They could not bear witness in court, make wills or bring legal actions. They were outside of Christian society and therefore outside the law, so it could not be an offence to defraud them, torture them or even kill them. A vestige of this problem survives in the word cretin, derived from the word Chrétien meaning Christian. A cretin, though suffering from iodine deficiency, might still have enough mental capacity to warrant being baptised, and thus being regarded as human. Anyone with less mental capacity than a cretin was non-human and so, like the deaf, unworthy of baptism. For theologians they were mere "lumps of flesh" - self sustaining giant tumours without souls, or rights, or any place in Christian society.

Mental infirmity, like physical infirmity, was a punishment from God. An interesting question for theologians was the degree of mental infirmity required to render a person subhuman. This was important because sub-humans were mere animals with no human souls. Without a soul they were not entitled to the privileges of humanity. They could not benefit from baptism nor from legal privileges. Like the excommunicated and outlaws, they were non-persons. They could not bear witness in court, make wills or bring legal actions. They were outside of Christian society and therefore outside the law, so it could not be an offence to defraud them, torture them or even kill them. A vestige of this problem survives in the word cretin, derived from the word Chrétien meaning Christian. A cretin, though suffering from iodine deficiency, might still have enough mental capacity to warrant being baptised, and thus being regarded as human. Anyone with less mental capacity than a cretin was non-human and so, like the deaf, unworthy of baptism. For theologians they were mere "lumps of flesh" - self sustaining giant tumours without souls, or rights, or any place in Christian society.

Christian ideas and priorities are made clear in its surviving buildings. Almost every ancient village in Europe has a church, but almost none had a hospital in the modern sense of the word before the Enlightenment. Before then hospitals were religious institutions built to offer hospitality to travelers. Very few provided medical care to the poor — Saint Bartholemew's Hospital in London is notable precisely because of its uniqueness. Surgery was prohibitted in religious hospitals because churchmen were not permitted to shed blood. Care was therefore generally of the type offered more recently by "Mother Theresa" - no medical intervention, no anasthetics, just basic care and a focus on religious conversion before death. The nearest the Church came to hospital in the modern sense was a Lazar House or leprosaria, a place to enforce the segregation of lepers; or mad house, such as Bethlehem Hospital ("Bedlam"), to enforce the segregation of the insane.

In the 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment, modern hospitals began to appear, serving medical needs and staffed by qualified physicians and surgeons. The goal of these hospitals was to use modern methods to cure patients rather than save their souls. They were founded by private individuals and secular authorities. For the first time since classical times, a clear distinction emerged between medicine and poor relief. Within the hospitals, separate specialist departments were set up for different types of patient. In England a voluntary hospital movement began in the early 18th century, with hospitals being founded in London. Westminster Hospital, founded in 1719, was promoted by a private bank (Hoare & Co). Guy's Hospital, founded in 1724, was funded from the bequest of Thomas Guy, a wealthy merchant. Other medical hospitals were founded in British cities through the eighteenth century, generally paid for by private subscriptions, often by Quakers, not by other religious institutions. Soon public dispensaries would be established too, providing medicine to the poor, free of charge. The first true hospital in North America was the Pennsylvania hospital, founded by Benjamin Franklin and fellow Quaker Thomas Bond in Philadelphia in 1751. Patients were treated free of charge and the hospital was funded through private donations.

Vestiges of traditional Christian attitudes remain - many Churches still discriminate against the handicapped in a variety of ways - employment, marriage, rights within the Church, etc although secular laws are slowly eliminating the ways they are allowed to discriminate. For example it took an anti-discrimination suit by the American Civil Liberties Union against the Oral Roberts University in the twenty-first century before disabled people were allowed on the campuses of all the God-inspired evangelical American universities9. It is notable that the worst excesses were particularly Christian. Before the Churches' rise to power, non-Christians had formed rational explanations for illness and infirmity. Socrates (in Plato's Cratylus) recognised that the deaf were just as intelligent as everyone else. When the Church was most powerful, the only people effectively exempt from its rules — rich and influential nobles — were able to teach their deaf children to read and write. In this way they circumvented Church restrictions, and such children were permitted to marry and inherit. If churchmen had thought about this, they could easily have reached the same conclusion as Socrates.

***

It is doubtful if the handicapped have ever, in any other cultural domain in human history, been more wronged and despised or treated with greater intolerance and inhumanity, than in Christendom7.

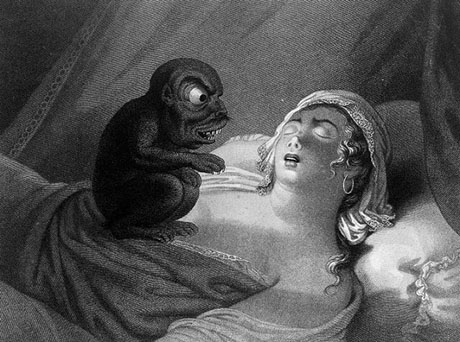

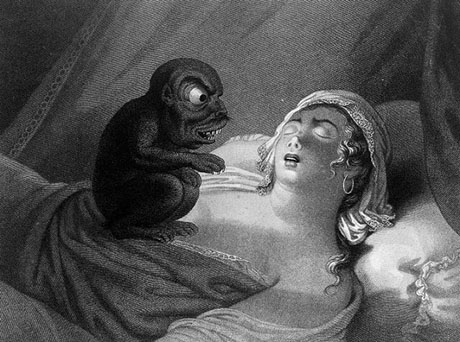

Changelings were sometimes regarded as half-breeds, the offspring of a human woman and an elf or other supernatural being. In other cases, unwanted children were regarded as Cambions. According to theologians, demons would adopt female form to seduce sleeping men and obtain their semen, then adopt male form to seduce sleeping women, and impregnate them with their ill-gotten semen. The offspring of such a union was a Cambion. The demon in female form was a succubus, and in male form was an incubus. St. Augustine in De Civitate Dei affirmed that there were too many attacks by incubi to deny them. Saint Thomas Aquinas also affirmed their existence, as did the Inquisitors' handbook Malleus Maleficarum.8.- Nightmare (1800) by Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard (1743 - 1809) .

- Oil on canvas, 35.3 x 41.7 cm. Vestsjaellands Art Museum, Denmark.

An incubus sits on a the chest of a sleeping woman, her husband unaware, next to her.

Another incubus, still familiar in the nineteenth century.

Detail, Jean Pierre Simon, Nightmare, 1810, Welcome Library

The bible is clear that deformities render a person unfit to be a Jewish priest, and the Church interpreted the relevant passages as referring also to Christian priests:

The Lord said to Moses, “Say to Aaron: ‘For the generations to come none of your descendants who has a defect may come near to offer the food of his God. No man who has any defect may come near: no man who is blind or lame, disfigured or deformed; no man with a crippled foot or hand, or who is a hunchback or a dwarf, or who has any eye defect, or who has festering or running sores or damaged testicles. No descendant of Aaron the priest who has any defect is to come near to present the food offerings to the Lord. He has a defect; he must not come near to offer the food of his God. He may eat the most holy food of his God, as well as the holy food; yet because of his defect, he must not go near the curtain or approach the altar, and so desecrate my sanctuary. I am the Lord, who makes them holy.’” (Leviticus 21:16-23)

So it was that any bodily deformities debar a man from becoming a priest. Even today physically handicapped priests are rare - and explicable by injuries sustained after ordination. God had no use for the physically impaired. Historically, physical handicaps were, along with servile birth and illegitimacy, bars to ordination. Canon 1029 of the Roman code of canon law still requires those to be ordained to have "appropriate physical qualities".Hubert Ahaus, "Holy Orders." The Catholic Encyclopedia.

Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911.

The first requisite for lawful ordination is a Divine vocation; by which is understood the action of God, whereby He selects some to be His special ministers, endowing them with the spiritual, mental, moral, and physical qualities required for the fitting discharge of their order and inspiring them with a sincere desire to enter the ecclesiastical state for God's honor and their own sanctification. The reality of this Divine call is manifested in general by sanctity of life, right faith, knowledge corresponding to the proper exercise of the order to which one is raised, absence of physical defects, the age required by the canons ...

Some diseases, handicaps and injuries were sufficient to prevent people being allowed in Christian congregations at all. For example, genital injuries debarred men from attending church: "No one who is emasculated or has his male organ cut off shall enter the assembly of the LORD." (Deuteronomy 23:1). Other examples we have already seen include Deafness being a bar to being a Christian, and lepers who were not permitted to enter churches after a priest has read the service for the dead for them (on the discovery of their disease, not their death). In all cases the justification for exclusion was biblical.

"Philip Verheyen dissecting his amputated limb", detail, Anonymous artist, c. 1715-1730.

Philip Verheyen had been a theology student destined for the priesthood, until his lower leg had to be amputated in 1675, debarring him from his vocation. (He kept his severed leg and subsequently became a famous anatomist and surgeon)

Christian ideas and priorities are made clear in its surviving buildings. Almost every ancient village in Europe has a church, but almost none had a hospital in the modern sense of the word before the Enlightenment. Before then hospitals were religious institutions built to offer hospitality to travelers. Very few provided medical care to the poor — Saint Bartholemew's Hospital in London is notable precisely because of its uniqueness. Surgery was prohibitted in religious hospitals because churchmen were not permitted to shed blood. Care was therefore generally of the type offered more recently by "Mother Theresa" - no medical intervention, no anasthetics, just basic care and a focus on religious conversion before death. The nearest the Church came to hospital in the modern sense was a Lazar House or leprosaria, a place to enforce the segregation of lepers; or mad house, such as Bethlehem Hospital ("Bedlam"), to enforce the segregation of the insane.

In the 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment, modern hospitals began to appear, serving medical needs and staffed by qualified physicians and surgeons. The goal of these hospitals was to use modern methods to cure patients rather than save their souls. They were founded by private individuals and secular authorities. For the first time since classical times, a clear distinction emerged between medicine and poor relief. Within the hospitals, separate specialist departments were set up for different types of patient. In England a voluntary hospital movement began in the early 18th century, with hospitals being founded in London. Westminster Hospital, founded in 1719, was promoted by a private bank (Hoare & Co). Guy's Hospital, founded in 1724, was funded from the bequest of Thomas Guy, a wealthy merchant. Other medical hospitals were founded in British cities through the eighteenth century, generally paid for by private subscriptions, often by Quakers, not by other religious institutions. Soon public dispensaries would be established too, providing medicine to the poor, free of charge. The first true hospital in North America was the Pennsylvania hospital, founded by Benjamin Franklin and fellow Quaker Thomas Bond in Philadelphia in 1751. Patients were treated free of charge and the hospital was funded through private donations.

Vestiges of traditional Christian attitudes remain - many Churches still discriminate against the handicapped in a variety of ways - employment, marriage, rights within the Church, etc although secular laws are slowly eliminating the ways they are allowed to discriminate. For example it took an anti-discrimination suit by the American Civil Liberties Union against the Oral Roberts University in the twenty-first century before disabled people were allowed on the campuses of all the God-inspired evangelical American universities9. It is notable that the worst excesses were particularly Christian. Before the Churches' rise to power, non-Christians had formed rational explanations for illness and infirmity. Socrates (in Plato's Cratylus) recognised that the deaf were just as intelligent as everyone else. When the Church was most powerful, the only people effectively exempt from its rules — rich and influential nobles — were able to teach their deaf children to read and write. In this way they circumvented Church restrictions, and such children were permitted to marry and inherit. If churchmen had thought about this, they could easily have reached the same conclusion as Socrates.

***

No comments:

Post a Comment