If a Job is Worth Doing, It's Worth Doing Poorly by L. Roger Owens

It was a common scene: Reynolds, our church's minister for adult discipleship, sitting on the sofa in my office, excitedly telling me about a new idea for ministry, usually one that would help us cross more faithfully the stubborn lines of class and race.

This time he was explaining his idea for a Christmas market. Tired of the much-celebrated but often-demeaning toy giveaways that some organizations sponsor for the poor at Christmas, Reynolds suggested that our church host a market.

Local social-service agencies would refer clients. Church members would donate new toys, and the church would sell them at drastically reduced prices. The church would give the proceeds back to the social-service agencies. Most importantly, parents would have their dignity preserved as they chose and purchased Christmas presents for their children.

My reservations weren't about the idea itself -- it perfectly aligned with the way of ministry we were trying to embody as a church.

I don't remember what questions I asked to show my reservations, but I must have asked questions like, "It sounds complicated -- do we have enough time to pull it together? Have you worked out the logistics? Will there be enough volunteers?" In other words, "Are you going to do it right?"

But I do remember his response: "If a job's worth doing, it's worth doing poorly."

In the next moment of silence, I heard my mother's voice screeching from my subconscious the mantra I'd heard a million times growing up: "If a job's worth doing, it's worth doing right."

And I heard my own one-word mantra -- "Excellence" -- that for four years I'd repeated in staff meetings. "In our ministries, we strive for excellence. We cross our t's and dot our i's. We do things right."

And I heard Jim Collins telling me, once again, "Good is the enemy of great."

And here is a staff member suggesting doing something less than great, implicitly critiquing one of my core leadership philosophies. "Let go," he was telling me, "and risk doing something badly."

There's wisdom in this saying, I now can admit -- wisdom I've since been trying to learn. Because the fear of doing something poorly can beset a leader in two ways.

First, it can lead to suffocating micromanagement. Committed to doing things right, the leader cannot give away control and let others work on their own.

Like the worst kind of helicopter parent, the leader hovers, meddles and interferes -- limiting the scope of ministry to what the leader can control, dispiriting staff and volunteers who long to have their initiative honored and their competence trusted, and leaving the leader stressed and exhausted. All to get things right, as he or she sees it.I was more prone to the second way the fear manifests itself: paralysis. Not wanting to start anything until I knew I could get it right, I struggled to start anything at all. And worse, I stood in the way of others. I was decidedly biased toward inaction.

This kind of bias prevents the very experimentation -- the testing, the trying -- that churches desperately need in our culture of constant, rapid change.

Imagine if God suffered in either of these two ways. There would have been no call of Abraham, no Israel, no disciples -- indeed, no church. Because none of these characters -- none of us -- always gets it right. And yet God’s Spirit still calls and equips, still allows us to fall and grow and learn.

Reynolds was just asking permission to try something new without guarantees of success. Permission to do something inelegantly, if needing to do it elegantly meant not doing it at all. Permission to throw something together quickly, if it was the right something, even if it wouldn’t be perfect.

He was asking permission to follow a Spirit that trusted him enough to let him fall.

“Okay,” I said. Then I added, “But if a job’s worth continuing to do, it’s worth doing better.”

We will test, try, experiment. We will stumble, no doubt. But we will also learn and improve and grow. We will not shut the door on excellence, but neither will we let excellence shut the door on innovation.

I stayed pastor of that church long enough to see one Christmas market. It was, by all accounts, a success. Reynolds stayed on staff long enough to coordinate a second market the next year.

This December the church sponsored its third. Traveling over Christmas, I had breakfast with Reynolds and Gair, who is still on the church’s staff, to reconnect. My favorite part of breakfast was sitting silently, listening to Gair tell Reynolds how wonderful the market was this year, and how much better -- twice the toys, twice the people served, better hospitality, better-trained volunteers, more-streamlined checkout, more agencies involved, more money donated. And only two toys left over.

Listening to her enthusiasm, I thought to myself: “Thank you, God, for giving us jobs worth doing.”

The Rev. Dr. L. Roger Owens is associate professor of leadership and ministry at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. He is an ordained Elder in the North Carolina Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church. Prior to coming to PTS, he served both urban and rural churches.

____________________________

Monday, March 16, 2015

What does the church look like if we take 'the ministry of the baptized, the priesthood of all believers' seriously? Sheryl Kujawa-Holbrook and Fredrica Harris Thompsett explore the ways people in small congregations are living out their baptism. Their actions, small and large, are having a profound impact on congregations, judicatories, communities and the institutions that educate clergy. Buy the book

This time he was explaining his idea for a Christmas market. Tired of the much-celebrated but often-demeaning toy giveaways that some organizations sponsor for the poor at Christmas, Reynolds suggested that our church host a market.

Local social-service agencies would refer clients. Church members would donate new toys, and the church would sell them at drastically reduced prices. The church would give the proceeds back to the social-service agencies. Most importantly, parents would have their dignity preserved as they chose and purchased Christmas presents for their children.

My reservations weren't about the idea itself -- it perfectly aligned with the way of ministry we were trying to embody as a church.

I don't remember what questions I asked to show my reservations, but I must have asked questions like, "It sounds complicated -- do we have enough time to pull it together? Have you worked out the logistics? Will there be enough volunteers?" In other words, "Are you going to do it right?"

But I do remember his response: "If a job's worth doing, it's worth doing poorly."

In the next moment of silence, I heard my mother's voice screeching from my subconscious the mantra I'd heard a million times growing up: "If a job's worth doing, it's worth doing right."

And I heard my own one-word mantra -- "Excellence" -- that for four years I'd repeated in staff meetings. "In our ministries, we strive for excellence. We cross our t's and dot our i's. We do things right."

And I heard Jim Collins telling me, once again, "Good is the enemy of great."

And here is a staff member suggesting doing something less than great, implicitly critiquing one of my core leadership philosophies. "Let go," he was telling me, "and risk doing something badly."

There's wisdom in this saying, I now can admit -- wisdom I've since been trying to learn. Because the fear of doing something poorly can beset a leader in two ways.

First, it can lead to suffocating micromanagement. Committed to doing things right, the leader cannot give away control and let others work on their own.

Like the worst kind of helicopter parent, the leader hovers, meddles and interferes -- limiting the scope of ministry to what the leader can control, dispiriting staff and volunteers who long to have their initiative honored and their competence trusted, and leaving the leader stressed and exhausted. All to get things right, as he or she sees it.I was more prone to the second way the fear manifests itself: paralysis. Not wanting to start anything until I knew I could get it right, I struggled to start anything at all. And worse, I stood in the way of others. I was decidedly biased toward inaction.

This kind of bias prevents the very experimentation -- the testing, the trying -- that churches desperately need in our culture of constant, rapid change.

Imagine if God suffered in either of these two ways. There would have been no call of Abraham, no Israel, no disciples -- indeed, no church. Because none of these characters -- none of us -- always gets it right. And yet God’s Spirit still calls and equips, still allows us to fall and grow and learn.

Reynolds was just asking permission to try something new without guarantees of success. Permission to do something inelegantly, if needing to do it elegantly meant not doing it at all. Permission to throw something together quickly, if it was the right something, even if it wouldn’t be perfect.

He was asking permission to follow a Spirit that trusted him enough to let him fall.

“Okay,” I said. Then I added, “But if a job’s worth continuing to do, it’s worth doing better.”

We will test, try, experiment. We will stumble, no doubt. But we will also learn and improve and grow. We will not shut the door on excellence, but neither will we let excellence shut the door on innovation.

I stayed pastor of that church long enough to see one Christmas market. It was, by all accounts, a success. Reynolds stayed on staff long enough to coordinate a second market the next year.

This December the church sponsored its third. Traveling over Christmas, I had breakfast with Reynolds and Gair, who is still on the church’s staff, to reconnect. My favorite part of breakfast was sitting silently, listening to Gair tell Reynolds how wonderful the market was this year, and how much better -- twice the toys, twice the people served, better hospitality, better-trained volunteers, more-streamlined checkout, more agencies involved, more money donated. And only two toys left over.

Listening to her enthusiasm, I thought to myself: “Thank you, God, for giving us jobs worth doing.”

The Rev. Dr. L. Roger Owens is associate professor of leadership and ministry at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. He is an ordained Elder in the North Carolina Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church. Prior to coming to PTS, he served both urban and rural churches.

____________________________

Monday, March 16, 2015

What does the church look like if we take 'the ministry of the baptized, the priesthood of all believers' seriously? Sheryl Kujawa-Holbrook and Fredrica Harris Thompsett explore the ways people in small congregations are living out their baptism. Their actions, small and large, are having a profound impact on congregations, judicatories, communities and the institutions that educate clergy. Buy the book

Many pastors stay at a new congregation for fewer than five years; according to Robert Harris, this can be explained, in part, because of the way that these clergy spend their first year or two. In this handbook, this veteran coach helps both experienced and new pastors enter a new congregation effectively.

Buy the book

From Congregational Ministry from the Alban Archive

How Your Congregation Learns by Tim Shapiro

Buy the book

From Congregational Ministry from the Alban Archive

How Your Congregation Learns by Tim Shapiro

What do you do when your congregation either needs or chooses to do something new? No one needs help in creating a list of new demands on congregational life. Any congregation, your congregation, is expected to think and behave in ways that it has not yet learned with knowledge it does not yet hold, writes Tim Shapiro from the Indianapolis Center for Congregations.

Congregations, or perhaps more precisely, congregational leaders, need to learn new skills all the time. Such are the demands on congregational life.

Congregations, or perhaps more precisely, congregational leaders, need to learn new skills all the time. Such are the demands on congregational life.

What do you do when your congregation either needs or chooses to do something new? Perhaps your congregation wants to serve the homeless, an entirely new endeavor. Maybe your congregation is working on a renovation of the building and it has been a decade since a significant building project. Maybe your congregation wants to think about worship or faith formation. Perhaps the new thing is addressing a long-term issue that the congregation has collectively avoided. No one needs help in creating a list of new demands on congregational life. Each can seem like starting a deep-space mission. Any congregation, your congregation, is expected to think and behave in ways that it has not yet learned with knowledge it does not yet hold.

Knowing how your congregation learns is essential to learning to do any number of activities. How congregations learn is a meta question that shapes the answer to all kinds of questions.

The Indianapolis Center for Congregations has worked with more than 3,000 Indiana congregations over 15 years. The Center has observed a learning framework used by congregations developing new capacities. The framework includes seven overarching behaviors. The behaviors apply to almost any congregational challenge. They are not complicated.

The learning framework is part of a deep structure of capacity development taking place in congregations that are effective at learning new skills. When a congregation adopts most of the activities that make up the framework, they are more likely to effectively address any challenge.

The seven behaviors do not come from a psychological framework, though they add to the emotional well-being of a congregation. They do not come from an organizational framework, though the activities strengthen the congregation as a system. The frame is religious in the sense that it reflects a theological understanding that congregations are basically healthy and able to sustain the learning they need to address challenges if given the right amount of assistance and time. The seven behaviors fortify strengths already present in a congregation while also enhancing the congregation’s relationship to its mission.

Here are the seven elements that make up the learning framework that the Center for Congregations has observed:

Congregations are by necessity learning all the time. New challenges require new capabilities that require learning. Whether paving the parking lot or training in monastic prayer, adopting the seven learning behaviors as a part of congregational practice strengthens the possibility of positive outcomes. Your congregation has all kinds of new challenges waiting and it deserves to learn its lessons well.

____________________________

A Journey with One's Peers: The Power of Group Learning Programs by Marlis McCollum

In this article from 2006, Marlis McCollum describes the power and promise of a trend toward peer learning groups for continuing education for clergy. She also offers eight pieces of advice from experts in the field. Seminaries and other organizations offer a plethora of continuing education programs for ministers, but many of these same organizations are conducting research to discover new continuing education models that can provide even more benefit and impact. What is being discovered may have the potential to transform the face of ministerial continuing education.

Peer group learning experiments, in particular, appear to hold great promise. Bruce Roberts, professor of congregational education and leadership at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis, is director of one such experiment, the Indiana Peer Group Study Program (PGSP), a program funded by the Lilly Endowment and based upon evaluation research Roberts conducted with Robert E. Reber of a peer group program initiated by The Dixon Foundation in Alabama in the early 1980s.

Of the 14 peer groups in the PGSP, six have completed their three-year programs of study. Without exception, Roberts says, participants “are all reporting being highly energized by what has happened, describing it as the best continuing education they’ve ever had. One participant said he thought the denominations should shut down all the individual events and just fund peer learning.”

There is evidence that the congregations have experienced the impact of their pastors’ participation in the peer group study experience, as well, though it’s difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, Roberts says, “The congregations are telling us that they have noticed a difference in their pastors—that the pastors have been more energetic, have started more programs, and have interacted better with the congregations than they had before.”

In the PGSP, the question of what is to be learned is turned over to participants. “We say to the clergy, ‘As a group, come up with a plan for your learning that all of you can get excited about and that you are willing to hold each other accountable for over the next three years.’ And what we’ve found is that that creates a lot of energy for continuing education.” In Roberts’ opinion, the accountability system the group provides is one of the keys to the program’s success. “When you send somebody away as an isolated individual, they may come back on fire, but they still end up in the old system, where there are no accountability structures in place, so there’s no ongoing reflection about what went on there, and pretty soon the learning just gets lost.”

Also at the core of the success of peer group learning, he believes, is the freedom each group has to decide on its learning agenda. “I don’t think it’s a good idea for someone outside of a given context to be giving advice to ministers about what they ought to be learning,” he says. “What ministers should be working on learning will depend on what’s going on in the context in which they work, what they are experiencing, and what they believe they need to work on.”

Michael Ross, executive director of the Pastors Institute in Anderson, Indiana, agrees. Ross recently completed a research project examining the combined findings of six studies on pastoral attrition (a project funded by the Louisville Institute), discovering that many departed ministers felt that their education—both seminary and postseminary—had left them ill-prepared, and needed to be more relevant to the congregations they pastored. “This whole notion of contextual education is on the front burner, but it has not made its way into lifelong learning plans,” Ross says.

Among the other seven primary factors that led to decisions to leave the ministry were a lack of connectedness and support, insufficient self-care, and poor “people skills”—some of the same areas in which the PGSP groups have chosen to focus their efforts. Most of the six PGSP groups who have completed their work focused on leadership skills, and most also paid attention to spiritual and self-nurturing practices. “They are all feeling the burnout, so they do have a spirituality component and a self-care component in their learning plans,” Roberts says.

The Institute for Clergy Excellence in Huntsville, Alabama, has developed its own peer group learning project, also funded by the Lilly Endowment, and is experiencing results similar to those of the PGSP groups. The project grew out of an earlier program that Institute Executive Director Larry Dill was instrumental in forming. In that program, groups of ministers from the North Alabama United Methodist Conference came together to work on their preaching. The current project expands on the earlier program in a number of ways: It is ecumenical, includes participants from a wide region, and includes not only preaching but also worship and leadership components. It has a lay component as well.

The project includes 11 groups, some of which are ending their first year of work together. Others are still working on designing their learning agendas. “It takes six months to a year for them to design their projects,” explains Dill. Like Roberts, Dill believes the key principles underlying the peer group learning model’s success are that the groups are self-selecting, they design their own learning agenda, they study together over time, and the members hold each other accountable for the learnings. “It’s not like going to a seminar,” he says. “Each time they meet we expect them to give evidence to one another about what they are learning.”

Dill finds particular power in the opportunity for the groups to design their own learning agendas. “That’s one of the most exciting and energizing aspects of this program. It’s based on the idea that the world is your classroom.” He cites the example of one group that worked with the Dzieci Theater Group of New York City to improve their preaching. “People from the school worked with the group on things like presence, breathing, and voice. The members of the group said it was really transformational for them. The freedom to experiment, to be creative, often winds up being transformational,” Dill says. In addition, the Institute encourages groups to change their plans as they go along. “It’s a plan that grows with them as they grow,” Dill says.

Involving the Laity

Involving the laity in the work of the groups has also proven a successful strategy. “There’s a lot of energy among the laity,” Dill says. Although originally included based on the premise that they would be helpful in implementing any changes the minister wished to make in worship, the laity’s participation has proven to be more influential in the group members’ efforts to improve their preaching, Dill says. “From the laity we heard comments like ‘I thought I could help my minister be a better preacher, but I couldn’t find a safe place to do that.’ So this program provided that safe space.”

As with their learning agendas, the groups are free to determine exactly how they will involve the laity. Some laity teams have been invited to participate in the ministers’ training sessions with outside speakers. Others have been offered the opportunity to travel with the groups. One group has developed an instrument it will use to have its laity teams evaluate its members’ preaching. Another group even invited its laity teams to participate in the design of its project. Recent research seems to indicate that lay participation in a pastor’s learning agenda may be more important than has previously been thought. In Ross’s research on pastoral attrition, a significant finding is that pastors who have left the ministry believe they would have had a better experience if their congregations had been more involved in the development of their learning programs.

“What we’re finding is that there seems to be a detachment of the pastor’s continuing education from the congregation’s involvement—and even their awareness. Former pastors seem to be saying they made a mistake in not involving the congregation earlier in their continuing education process.” The way in which pastors believe congregations could have helped the most, Ross says, is by providing input into the minister’s lifelong learning plan. Much of the learning pastors receive in continuing education programs “is misunderstood or mischanneled because the congregation is often unaware of what the pastor is doing,” he says.

Dean McDonald, director of the Cathedral College of Preachers, says the College has found it very effective to involve the laity in its core curriculum program. “Participants in that program form a listening group of members of their congregation to provide feedback on their sermons. This has tremendous benefit to the preacher, who now has a lay group that has an increased sensitivity to what goes into planning worship and preaching.”

“Clergy are very reticent to ask for things they think others might view as being just for themselves,” adds Dean Wolfe, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Kansas. “That’s why it’s very important to involve lay members.” When the laity become involved in a minister’s continuing education, he says, they can more readily recognize its benefits not only to the minister but also to the congregation.

Along that same vein, other organizations have begun encouraging clergy to involve their lay members in their continuing education efforts, and they are receiving positive feedback about these initiatives. Andrew Warner, pastor of Plymouth United Church of Christ in Milwaukee, says one of the most beneficial continuing education events in which he participated was a stewardship partners program held last year by the Wisconsin Conference of the United Church of Christ. “In order to participate I had to bring laypeople from my church to participate with me. The idea was to recruit a team that could learn with me.” Warner recruited two members of his congregation to be part of his team, an architect and a development director for a nonprofit organization. The participation of these members provided continuity and ongoing inspiration for Warner when he returned to his pastorate. “We could have a conversation about what we’d learned and each of us had different insights, so instead of having only what I had gleaned from the program I also had the insights of my team members. It made the experience more well-rounded. And instead of just having a great experience away from the church I could continue to process that experience with others when I returned.”

Group Learning Benefits

Peer group learning project directors and researchers believe this ability to continue to reflect on and build on the learnings from a continuing education event is one of the primary benefits of group learning, whether one’s group consists of other clergy or members of one’s congregation.

“There’s an unusual dynamic that develops when learning with a peer group,” says Dill, recalling one group that decided to attend a conference on homiletics together. “Initially I looked upon that as not a very creative idea, but soon I realized that to go to that event together was quite different from going to it as individuals. Within the group there were three women and five men, and after the event they realized they had heard the speakers very differently. The men had related more positively to the male speakers than to the female speakers, and for the women it was just the opposite. So they have begun exploring why that is. That’s something they wouldn’t have discovered if they had attended that conference by themselves.”

Dill also believes there is a cumulative knowledge available to ministers in the group learning experience, whether that takes the shape of shared insights, information, advice, tips, or reminders of wisdom shared by guest speakers or trainers. “Sometimes we aren’t able to hear something at the time that it is said. Later, when we are ready to hear it, a group member can remind us.”

Wolfe sees other benefits of peer group learning. “Traditionally,” he says, “it has been very difficult for clergy to build community with each other. There is often a competitiveness among clergy, a reticence to share. Groups like these break those negative patterns and help clergy establish more positive connections with one another.”

Jennifer Thomas, pastor of Lake Park Lutheran Church in Milwaukee, says her most helpful continuing education experiences have involved colleague groups, one of which is Christ Clarion Fellowship, a group of young clergy that meets once a year for a four-day retreat. Each retreat has a topical focus, such as public witness or devotional practices, which is explored in depth. Fellowship is an integral part of the event, as is mentoring, Thomas says. She considers the ecumenical and interracial composition of the group another benefit. “We wrestle with the same issues, but because our contexts are different we learn about other denominations. We help each other hone our gifts and skills, and as we develop relationships with one another we can challenge and affirm each other as well.”

Warner, a co-founder of Christ Clarion Fellowship, wouldn’t miss the annual retreat. “I consider that a real anchor group. The clergy in that group are the ones I stay in touch with throughout the year.” Warner recognizes the increasing returns from relationships that have developed over time in the group. “We can press each other in ways that we wouldn’t if we were coming together for the first time. For instance, at our last meeting we had a very honest conversation about clergy salaries. That’s not something that gets talked about a lot in deep and personal ways.”

Learning with laity offers added benefits to the group learning experience, Wolfe believes. “Most doctor of ministry degrees require participation of lay people on the journey,” he says. “It involves the laity in some creative learning. It also counters some of the resistance clergy sometimes experience from the parish to their continuing education proposals (‘Well, gee, you already get vacation’). If the congregation participates in the continuing education experience, it dissipates some of that resistance.”

Permission to Risk

All of these initiatives began as experiments, and in Roberts’ opinion, the freedom to experiment is essential if clergy are to continue to be supported in their lifelong learning efforts. This freedom, he says, needs to be extended to both those who design continuing education programs for clergy and to clergy themselves. Both, he says, need the opportunity to try some new things and to sometimes fail when they do so, with the understanding that even failed experiments provide valuable information that can help to shape future efforts.

“I think we ought to ask of clergy, ‘What energizes you when you think about learning? What really grabs you and is something you really want to do?’ And then we ought to encourage them to go and do it. In terms of adult learning, one thing leads to another. So even if it’s not quite on the mark of what the congregation thinks the pastor needs to learn, getting the pastor involved in something that excites and motivates him or her will be well worth it to the congregation as well. To congregations, I would say ‘Pastors need time away to focus their thoughts, to pursue study, and to continue their learning, so fund their continuing education. It will pay off,’” says Roberts.

In Roberts’ opinion, experimentation in continuing education may not only be a shot in the arm to individual ministers, but a possible remedy for other difficulties facing mainline denominations. “Let’s face it, for the most part the oldline churches are in serious decline. We need something to shake up what’s going on in those systems, and it’s not going to happen unless clergy find the support they need to take some risks, to try some new things, and to understand that even if those things don’t work out, they learned something. Congregations are like oil fields; you have to keep drilling until you find the energy. The assumption is that it is there someplace.”

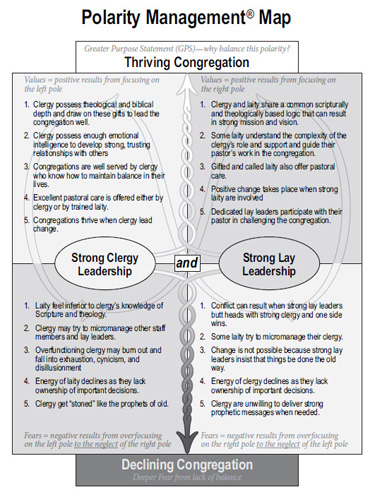

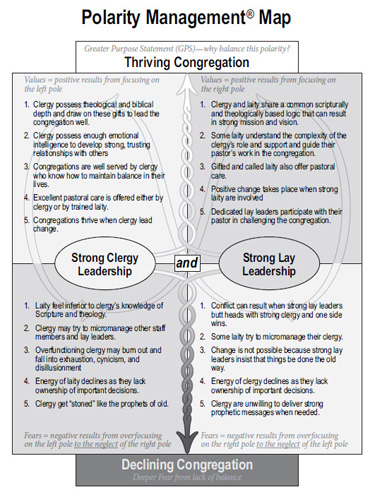

Thriving congregations have found ways to empower their clergy and to empower their laity. It is important to do both, write Roy Oswald and Barry Johnson in this excerpt from their book Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities. John and Brigetta were pastors of neighboring congregations. Even though they represented different denominations, their congregations were quite similar. Both had approximately 110 members attending Sunday worship, and both congregations had been stuck at that number for the past eight years. John and Brigetta knew each other well, as they belonged to the same clergy support group, yet their leadership styles differed greatly.

Brigetta was a tough-thinking woman who made most of the decisions at Good Samaritan Church. She had a strong, driven, Type-A personality. Brigetta had a clear vision of where the congregation should be headed, and she worked tirelessly at getting laypeople to carry out her vision. Although she had great ideas, she continually encountered lackluster support for these proposals from the board and committee members. Some lay leaders had tried to revise some of her ideas to make them more relevant to congregational needs, but she insisted on their doing things her way. Brigetta repeatedly rebuffed their attempts to gain some ownership of her plans by incorporating some of their own, and in the end, they acquiesced to her. Over time, members who had leadership capacities simply stopped serving on congregational boards and committees. Brigetta had not noticed that lay leaders lacked enthusiasm because they felt they were treated as lackeys whose purpose was to carry out her vision. She, on the other hand, complained to her colleagues that she wished she had just a few capable lay leaders who wanted to do something to make the congregation thrive.

John was laid-back and easygoing. He also had a natural proclivity to pursue peace at all costs. Early in his tenure at St. John’s, he had tried exercising leadership but had found himself quickly overruled by strong-willed lay leaders who disagreed with the changes he wanted to make. After several attempts with the same results, he decided to offer the congregation excellent pastoral care and leave the leadership of the congregation in the hands of the strong lay leaders. He saw himself as carrying out the directions his lay leaders set for him, and he seemed willing to pay this price to keep the peace. Besides, these lay leaders were an intimidating bunch. They were tough, successful executives in their corporate settings, and in their opinion John knew little about either leadership or management. Sometimes he knew that what they were proposing would not work, because he was in touch with a much broader segment of the congregation. But he would bite his tongue and go along with their proposals, though his heart was not in them, and he gave only token support to implementing their ideas.

The Polarity to Be Managed

Here were two congregations going nowhere. In each case, there was no partnership between clergy and lay leaders. The congregations were stuck on alternate poles of this polarity, and both were experiencing more and more of the downside of their respective poles.

A polarity is a pair of truths that are interdependent. Neither truth stands alone. They complement each other. Congregations often find themselves in power struggles over the two poles of a polarity. Both sides believe strongly that they are right. People on each side assume that if they are right, their opponents must be wrong—classic “either/or” thinking. Either we are right or they are right—and we know we are right! When people argue about the two truths, both sides will be right, and they will need each other to experience the whole truth.

Let’s take a look at each quadrant in the “Strong Clergy Leadership and Strong Lay Leadership” polarity in detail:

The Upside of Strong Clergy Leadership

The Upside of Strong Clergy Leadership

single sheet of paper and ask for an hour’s discussion at the next board meeting. The question that needs to be asked at such a time is this: “Are we managing this polarity well or managing it poorly?” If there is consensus that the congregation is managing it poorly, the board can ask for suggestions of action steps that might bring the two poles into better balance. If the suggestions are not particularly robust, a task force can be appointed to study the polarity and bring recommendations. Managing this polarity is worth that expenditure of energy.

__________________________________________________________

Adapted from Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities by Roy M. Oswald and Barry Johnson, copyright © 2010 by the Alban Institute. All rights reserved.

___________________________________________________

Visit Alban.org

What do you do when your congregation either needs or chooses to do something new? Perhaps your congregation wants to serve the homeless, an entirely new endeavor. Maybe your congregation is working on a renovation of the building and it has been a decade since a significant building project. Maybe your congregation wants to think about worship or faith formation. Perhaps the new thing is addressing a long-term issue that the congregation has collectively avoided. No one needs help in creating a list of new demands on congregational life. Each can seem like starting a deep-space mission. Any congregation, your congregation, is expected to think and behave in ways that it has not yet learned with knowledge it does not yet hold.

Knowing how your congregation learns is essential to learning to do any number of activities. How congregations learn is a meta question that shapes the answer to all kinds of questions.

The Indianapolis Center for Congregations has worked with more than 3,000 Indiana congregations over 15 years. The Center has observed a learning framework used by congregations developing new capacities. The framework includes seven overarching behaviors. The behaviors apply to almost any congregational challenge. They are not complicated.

The learning framework is part of a deep structure of capacity development taking place in congregations that are effective at learning new skills. When a congregation adopts most of the activities that make up the framework, they are more likely to effectively address any challenge.

The seven behaviors do not come from a psychological framework, though they add to the emotional well-being of a congregation. They do not come from an organizational framework, though the activities strengthen the congregation as a system. The frame is religious in the sense that it reflects a theological understanding that congregations are basically healthy and able to sustain the learning they need to address challenges if given the right amount of assistance and time. The seven behaviors fortify strengths already present in a congregation while also enhancing the congregation’s relationship to its mission.

Here are the seven elements that make up the learning framework that the Center for Congregations has observed:

- Congregations that learn well find and use outside resources.Congregations learn best about almost any topic when they use an outside resource in juxtaposition with their own ingenuity. An outside resource provides new perspective. The congregation’s ingenuity makes sure the learning is contextual and relevant to the particular congregation’s faith experience.

- Congregations that learn well live within a worldview of theological coherence. Congregations that are grounded in a lucid theological perspective are more likely to have the maturity to act consistently with their religious commitments. This coherence provides opportunities for God to be noticed during the learning. Cues of theological coherence show up in mission statements. It is supported by adult education. Theological coherence is exhibited in everyday conversation—prayer during hospital visits, comments in hallways, Facebook messages, and so on. Learning to think clearly about faith, and articulate that faith publicly, aids congregational learning.

- Congregations that learn well ask open-ended questions and practice active listening. Congregations learn when congregants do not assume there is a pre-determined answer to complex issues. It is obvious but rarely practiced: human beings, including congregants, learn best by asking questions for which they don’t know the answer.

- Congregations learn well when clergy and laity learn together. It is not just that clergy and laity should work together. It is that they need to learn together. When shared learning takes place, respect and trust grows. Projects maintain their momentum because they are not too dependent on either clergy or laity.

- Congregations learn well by attending to rites of passages. When new learning is taking place, it is important for congregations to pay attention to tender and mighty moments of existence: birth, graduation, marriage, divorce, illness, recovery, and death. Nothing teaches like life. Attending appropriately to rites of passages is also a way to practice theological coherence.

- Congregations learn well when they slow things down. Creating a sense of urgency makes sense when there is an emergency or when the congregation is becoming stagnant. Some congregations need a sense of urgency to consider a new endeavor, but are best served when they use their momentum to discern, not rush to action. Learning requires thoughtfulness, which requires time. Slowing things down is a way for congregations to allow their thinking to catch up with their praying and their praying to catch up with their thinking.

- Congregations learn well when they say “no” and say “yes”: When a congregation takes on a new initiative, another activity likely needs to be discarded. Congregations that affirm what matters most as well as that which matters less are best able to gain new capacity to address their challenges. Congregational capacity is not a zero-sum game. Focus is.

Congregations are by necessity learning all the time. New challenges require new capabilities that require learning. Whether paving the parking lot or training in monastic prayer, adopting the seven learning behaviors as a part of congregational practice strengthens the possibility of positive outcomes. Your congregation has all kinds of new challenges waiting and it deserves to learn its lessons well.

—

Tim Shapiro is president of the Indianapolis Center for Congregations. Prior to this, he served 18 years in pastoral ministry, 14 of those at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Xenia, Ohio. Prior to his service at Westminster, he was pastor of Bethlehem Presbyterian Church in Logansport, Indiana. He is the co-author of Holy Places: Matching Sacred Space with Mission and Message.____________________________

A Journey with One's Peers: The Power of Group Learning Programs by Marlis McCollum

In this article from 2006, Marlis McCollum describes the power and promise of a trend toward peer learning groups for continuing education for clergy. She also offers eight pieces of advice from experts in the field. Seminaries and other organizations offer a plethora of continuing education programs for ministers, but many of these same organizations are conducting research to discover new continuing education models that can provide even more benefit and impact. What is being discovered may have the potential to transform the face of ministerial continuing education.

Peer group learning experiments, in particular, appear to hold great promise. Bruce Roberts, professor of congregational education and leadership at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis, is director of one such experiment, the Indiana Peer Group Study Program (PGSP), a program funded by the Lilly Endowment and based upon evaluation research Roberts conducted with Robert E. Reber of a peer group program initiated by The Dixon Foundation in Alabama in the early 1980s.

Of the 14 peer groups in the PGSP, six have completed their three-year programs of study. Without exception, Roberts says, participants “are all reporting being highly energized by what has happened, describing it as the best continuing education they’ve ever had. One participant said he thought the denominations should shut down all the individual events and just fund peer learning.”

There is evidence that the congregations have experienced the impact of their pastors’ participation in the peer group study experience, as well, though it’s difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, Roberts says, “The congregations are telling us that they have noticed a difference in their pastors—that the pastors have been more energetic, have started more programs, and have interacted better with the congregations than they had before.”

In the PGSP, the question of what is to be learned is turned over to participants. “We say to the clergy, ‘As a group, come up with a plan for your learning that all of you can get excited about and that you are willing to hold each other accountable for over the next three years.’ And what we’ve found is that that creates a lot of energy for continuing education.” In Roberts’ opinion, the accountability system the group provides is one of the keys to the program’s success. “When you send somebody away as an isolated individual, they may come back on fire, but they still end up in the old system, where there are no accountability structures in place, so there’s no ongoing reflection about what went on there, and pretty soon the learning just gets lost.”

Also at the core of the success of peer group learning, he believes, is the freedom each group has to decide on its learning agenda. “I don’t think it’s a good idea for someone outside of a given context to be giving advice to ministers about what they ought to be learning,” he says. “What ministers should be working on learning will depend on what’s going on in the context in which they work, what they are experiencing, and what they believe they need to work on.”

Michael Ross, executive director of the Pastors Institute in Anderson, Indiana, agrees. Ross recently completed a research project examining the combined findings of six studies on pastoral attrition (a project funded by the Louisville Institute), discovering that many departed ministers felt that their education—both seminary and postseminary—had left them ill-prepared, and needed to be more relevant to the congregations they pastored. “This whole notion of contextual education is on the front burner, but it has not made its way into lifelong learning plans,” Ross says.

Among the other seven primary factors that led to decisions to leave the ministry were a lack of connectedness and support, insufficient self-care, and poor “people skills”—some of the same areas in which the PGSP groups have chosen to focus their efforts. Most of the six PGSP groups who have completed their work focused on leadership skills, and most also paid attention to spiritual and self-nurturing practices. “They are all feeling the burnout, so they do have a spirituality component and a self-care component in their learning plans,” Roberts says.

The Institute for Clergy Excellence in Huntsville, Alabama, has developed its own peer group learning project, also funded by the Lilly Endowment, and is experiencing results similar to those of the PGSP groups. The project grew out of an earlier program that Institute Executive Director Larry Dill was instrumental in forming. In that program, groups of ministers from the North Alabama United Methodist Conference came together to work on their preaching. The current project expands on the earlier program in a number of ways: It is ecumenical, includes participants from a wide region, and includes not only preaching but also worship and leadership components. It has a lay component as well.

The project includes 11 groups, some of which are ending their first year of work together. Others are still working on designing their learning agendas. “It takes six months to a year for them to design their projects,” explains Dill. Like Roberts, Dill believes the key principles underlying the peer group learning model’s success are that the groups are self-selecting, they design their own learning agenda, they study together over time, and the members hold each other accountable for the learnings. “It’s not like going to a seminar,” he says. “Each time they meet we expect them to give evidence to one another about what they are learning.”

Dill finds particular power in the opportunity for the groups to design their own learning agendas. “That’s one of the most exciting and energizing aspects of this program. It’s based on the idea that the world is your classroom.” He cites the example of one group that worked with the Dzieci Theater Group of New York City to improve their preaching. “People from the school worked with the group on things like presence, breathing, and voice. The members of the group said it was really transformational for them. The freedom to experiment, to be creative, often winds up being transformational,” Dill says. In addition, the Institute encourages groups to change their plans as they go along. “It’s a plan that grows with them as they grow,” Dill says.

Involving the Laity

Involving the laity in the work of the groups has also proven a successful strategy. “There’s a lot of energy among the laity,” Dill says. Although originally included based on the premise that they would be helpful in implementing any changes the minister wished to make in worship, the laity’s participation has proven to be more influential in the group members’ efforts to improve their preaching, Dill says. “From the laity we heard comments like ‘I thought I could help my minister be a better preacher, but I couldn’t find a safe place to do that.’ So this program provided that safe space.”

As with their learning agendas, the groups are free to determine exactly how they will involve the laity. Some laity teams have been invited to participate in the ministers’ training sessions with outside speakers. Others have been offered the opportunity to travel with the groups. One group has developed an instrument it will use to have its laity teams evaluate its members’ preaching. Another group even invited its laity teams to participate in the design of its project. Recent research seems to indicate that lay participation in a pastor’s learning agenda may be more important than has previously been thought. In Ross’s research on pastoral attrition, a significant finding is that pastors who have left the ministry believe they would have had a better experience if their congregations had been more involved in the development of their learning programs.

“What we’re finding is that there seems to be a detachment of the pastor’s continuing education from the congregation’s involvement—and even their awareness. Former pastors seem to be saying they made a mistake in not involving the congregation earlier in their continuing education process.” The way in which pastors believe congregations could have helped the most, Ross says, is by providing input into the minister’s lifelong learning plan. Much of the learning pastors receive in continuing education programs “is misunderstood or mischanneled because the congregation is often unaware of what the pastor is doing,” he says.

Dean McDonald, director of the Cathedral College of Preachers, says the College has found it very effective to involve the laity in its core curriculum program. “Participants in that program form a listening group of members of their congregation to provide feedback on their sermons. This has tremendous benefit to the preacher, who now has a lay group that has an increased sensitivity to what goes into planning worship and preaching.”

“Clergy are very reticent to ask for things they think others might view as being just for themselves,” adds Dean Wolfe, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Kansas. “That’s why it’s very important to involve lay members.” When the laity become involved in a minister’s continuing education, he says, they can more readily recognize its benefits not only to the minister but also to the congregation.

Along that same vein, other organizations have begun encouraging clergy to involve their lay members in their continuing education efforts, and they are receiving positive feedback about these initiatives. Andrew Warner, pastor of Plymouth United Church of Christ in Milwaukee, says one of the most beneficial continuing education events in which he participated was a stewardship partners program held last year by the Wisconsin Conference of the United Church of Christ. “In order to participate I had to bring laypeople from my church to participate with me. The idea was to recruit a team that could learn with me.” Warner recruited two members of his congregation to be part of his team, an architect and a development director for a nonprofit organization. The participation of these members provided continuity and ongoing inspiration for Warner when he returned to his pastorate. “We could have a conversation about what we’d learned and each of us had different insights, so instead of having only what I had gleaned from the program I also had the insights of my team members. It made the experience more well-rounded. And instead of just having a great experience away from the church I could continue to process that experience with others when I returned.”

Group Learning Benefits

Peer group learning project directors and researchers believe this ability to continue to reflect on and build on the learnings from a continuing education event is one of the primary benefits of group learning, whether one’s group consists of other clergy or members of one’s congregation.

“There’s an unusual dynamic that develops when learning with a peer group,” says Dill, recalling one group that decided to attend a conference on homiletics together. “Initially I looked upon that as not a very creative idea, but soon I realized that to go to that event together was quite different from going to it as individuals. Within the group there were three women and five men, and after the event they realized they had heard the speakers very differently. The men had related more positively to the male speakers than to the female speakers, and for the women it was just the opposite. So they have begun exploring why that is. That’s something they wouldn’t have discovered if they had attended that conference by themselves.”

Dill also believes there is a cumulative knowledge available to ministers in the group learning experience, whether that takes the shape of shared insights, information, advice, tips, or reminders of wisdom shared by guest speakers or trainers. “Sometimes we aren’t able to hear something at the time that it is said. Later, when we are ready to hear it, a group member can remind us.”

Wolfe sees other benefits of peer group learning. “Traditionally,” he says, “it has been very difficult for clergy to build community with each other. There is often a competitiveness among clergy, a reticence to share. Groups like these break those negative patterns and help clergy establish more positive connections with one another.”

Jennifer Thomas, pastor of Lake Park Lutheran Church in Milwaukee, says her most helpful continuing education experiences have involved colleague groups, one of which is Christ Clarion Fellowship, a group of young clergy that meets once a year for a four-day retreat. Each retreat has a topical focus, such as public witness or devotional practices, which is explored in depth. Fellowship is an integral part of the event, as is mentoring, Thomas says. She considers the ecumenical and interracial composition of the group another benefit. “We wrestle with the same issues, but because our contexts are different we learn about other denominations. We help each other hone our gifts and skills, and as we develop relationships with one another we can challenge and affirm each other as well.”

Warner, a co-founder of Christ Clarion Fellowship, wouldn’t miss the annual retreat. “I consider that a real anchor group. The clergy in that group are the ones I stay in touch with throughout the year.” Warner recognizes the increasing returns from relationships that have developed over time in the group. “We can press each other in ways that we wouldn’t if we were coming together for the first time. For instance, at our last meeting we had a very honest conversation about clergy salaries. That’s not something that gets talked about a lot in deep and personal ways.”

Learning with laity offers added benefits to the group learning experience, Wolfe believes. “Most doctor of ministry degrees require participation of lay people on the journey,” he says. “It involves the laity in some creative learning. It also counters some of the resistance clergy sometimes experience from the parish to their continuing education proposals (‘Well, gee, you already get vacation’). If the congregation participates in the continuing education experience, it dissipates some of that resistance.”

Permission to Risk

All of these initiatives began as experiments, and in Roberts’ opinion, the freedom to experiment is essential if clergy are to continue to be supported in their lifelong learning efforts. This freedom, he says, needs to be extended to both those who design continuing education programs for clergy and to clergy themselves. Both, he says, need the opportunity to try some new things and to sometimes fail when they do so, with the understanding that even failed experiments provide valuable information that can help to shape future efforts.

“I think we ought to ask of clergy, ‘What energizes you when you think about learning? What really grabs you and is something you really want to do?’ And then we ought to encourage them to go and do it. In terms of adult learning, one thing leads to another. So even if it’s not quite on the mark of what the congregation thinks the pastor needs to learn, getting the pastor involved in something that excites and motivates him or her will be well worth it to the congregation as well. To congregations, I would say ‘Pastors need time away to focus their thoughts, to pursue study, and to continue their learning, so fund their continuing education. It will pay off,’” says Roberts.

In Roberts’ opinion, experimentation in continuing education may not only be a shot in the arm to individual ministers, but a possible remedy for other difficulties facing mainline denominations. “Let’s face it, for the most part the oldline churches are in serious decline. We need something to shake up what’s going on in those systems, and it’s not going to happen unless clergy find the support they need to take some risks, to try some new things, and to understand that even if those things don’t work out, they learned something. Congregations are like oil fields; you have to keep drilling until you find the energy. The assumption is that it is there someplace.”

Continuing Education Advice from the Experts

Make continuing education a priority. “Value continuing education,”says Dean Wolfe, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Kansas.“If you make it a priority,it tends to happen.”

Pursue excellence. Recognize that there is a qualitative difference among the continuing education programs available.“Talk with others about their experiences to determine which programs are best,”Wolfe suggests,“and don’t be afraid to take a program that will challenge you.Those programs are very often where the juice is.”

Involve others. Form a peer learning group or take another minister or a member of your congregation with you to continuing education events,advises Bruce Roberts,director of the Indiana Peer Group Study Program and professor of congregational education and leadership at Christian Theological Seminary.These “others”can provide a structure of support and accountability for the minister.

Take charge of your own learning. Design your own learning plan,and don’t limit your continuing education plan to the offerings made available through institutions and organizations, suggests Larry Dill,executive director of the Institute for Clergy Excellence.

Keep stimulating yourself intellectually. “Most of the satisfied ministers I know are people who always find something new to work on,something new to learn. I think that’s what keeps them fresh,”says Wolfe.

Follow your passions. Don’t be afraid of asking for what you want,Roberts advises.Taking care of one’s own needs and following one’s own passions,he believes,will foster enthusiasm for learning and energy for one’s ministry,so the congregation is the ultimate winner.

Cultivate advocates. “Pastors need to cultivate advocates in their pastorate and in the judicatory who will communicate to others that the overall health of the pastor is important,and that if it’s not attended to the congregation will suffer,”says Dean McDonald,director of the Cathedral College of Preachers.

Be open about your continuing education endeavors. Share your continuing education plan with your board or your vestry and encourage them to hold you accountable,suggests Darren Elin,rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Saginaw,Michigan. Sharing also has other benefits,notes Wolfe:“When you reveal yourself as a learner it engages other people to be learners as well.”

____________________________

Failure to Thrive by Roy Oswald and Barry JohnsonThriving congregations have found ways to empower their clergy and to empower their laity. It is important to do both, write Roy Oswald and Barry Johnson in this excerpt from their book Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities. John and Brigetta were pastors of neighboring congregations. Even though they represented different denominations, their congregations were quite similar. Both had approximately 110 members attending Sunday worship, and both congregations had been stuck at that number for the past eight years. John and Brigetta knew each other well, as they belonged to the same clergy support group, yet their leadership styles differed greatly.

Brigetta was a tough-thinking woman who made most of the decisions at Good Samaritan Church. She had a strong, driven, Type-A personality. Brigetta had a clear vision of where the congregation should be headed, and she worked tirelessly at getting laypeople to carry out her vision. Although she had great ideas, she continually encountered lackluster support for these proposals from the board and committee members. Some lay leaders had tried to revise some of her ideas to make them more relevant to congregational needs, but she insisted on their doing things her way. Brigetta repeatedly rebuffed their attempts to gain some ownership of her plans by incorporating some of their own, and in the end, they acquiesced to her. Over time, members who had leadership capacities simply stopped serving on congregational boards and committees. Brigetta had not noticed that lay leaders lacked enthusiasm because they felt they were treated as lackeys whose purpose was to carry out her vision. She, on the other hand, complained to her colleagues that she wished she had just a few capable lay leaders who wanted to do something to make the congregation thrive.

John was laid-back and easygoing. He also had a natural proclivity to pursue peace at all costs. Early in his tenure at St. John’s, he had tried exercising leadership but had found himself quickly overruled by strong-willed lay leaders who disagreed with the changes he wanted to make. After several attempts with the same results, he decided to offer the congregation excellent pastoral care and leave the leadership of the congregation in the hands of the strong lay leaders. He saw himself as carrying out the directions his lay leaders set for him, and he seemed willing to pay this price to keep the peace. Besides, these lay leaders were an intimidating bunch. They were tough, successful executives in their corporate settings, and in their opinion John knew little about either leadership or management. Sometimes he knew that what they were proposing would not work, because he was in touch with a much broader segment of the congregation. But he would bite his tongue and go along with their proposals, though his heart was not in them, and he gave only token support to implementing their ideas.

The Polarity to Be Managed

Here were two congregations going nowhere. In each case, there was no partnership between clergy and lay leaders. The congregations were stuck on alternate poles of this polarity, and both were experiencing more and more of the downside of their respective poles.

A polarity is a pair of truths that are interdependent. Neither truth stands alone. They complement each other. Congregations often find themselves in power struggles over the two poles of a polarity. Both sides believe strongly that they are right. People on each side assume that if they are right, their opponents must be wrong—classic “either/or” thinking. Either we are right or they are right—and we know we are right! When people argue about the two truths, both sides will be right, and they will need each other to experience the whole truth.

Let’s take a look at each quadrant in the “Strong Clergy Leadership and Strong Lay Leadership” polarity in detail:

- Clergy possess theological and biblical depth and draw on those gifts to lead the congregation well

- Clergy possess enough emotional intelligence to develop strong, trusting relationships with others

- Congregations are well served by clergy who know how to maintain balance in their lives

- Excellent pastoral care is offered

- Congregations thrive when clergy lead congregational change

- Strong prophetic messages are delivered when necessary

- Clergy and laity share a common scripturally and theologically based logic that can result in strong mission and vision

- Some laity understand the complexity of the clergy’s role and support and guide their pastor’s work in the congregation

- Gifted and called laity also offer pastoral care

- Positive change takes place in a congregation when strong lay leaders are involved

- Dedicated lay leaders participate with their pastor in challenging the congregation

- Some laity may feel inferior to clergy in their knowledge of scripture, theology, and congregational life

- Clergy may try to micromanage other staff members and lay leaders

- Overfunctioning clergy may burn out and fall into exhaustion, cynicism, and disillusionment

- Lay leaders’ energy declines because they lack ownership of important decisions

- Clergy are, so to speak, stoned to death like the prophets of old

- Conflict can result when strong lay leaders butt heads with strong clergy, and one side wins

- Some laity try to micromanage their clergy

- Change is not possible because strong lay leaders insist that things be done the old way

- The energy of clergy declines as they lack ownership of important decisions

- Clergy are unwilling to deliver strong, prophetic messages

single sheet of paper and ask for an hour’s discussion at the next board meeting. The question that needs to be asked at such a time is this: “Are we managing this polarity well or managing it poorly?” If there is consensus that the congregation is managing it poorly, the board can ask for suggestions of action steps that might bring the two poles into better balance. If the suggestions are not particularly robust, a task force can be appointed to study the polarity and bring recommendations. Managing this polarity is worth that expenditure of energy.

__________________________________________________________

Adapted from Managing Polarities in Congregations: Eight Keys for Thriving Faith Communities by Roy M. Oswald and Barry Johnson, copyright © 2010 by the Alban Institute. All rights reserved.

___________________________________________________

Visit Alban.org

STAY CONNECTED

Alban

312 Blackwell Street, Suite 101

Durham, North Carolina 27701 United States

____________________________

____________________________

No comments:

Post a Comment